Maresha/ Beit Guvrin

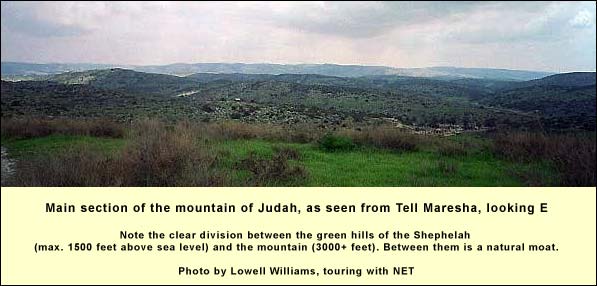

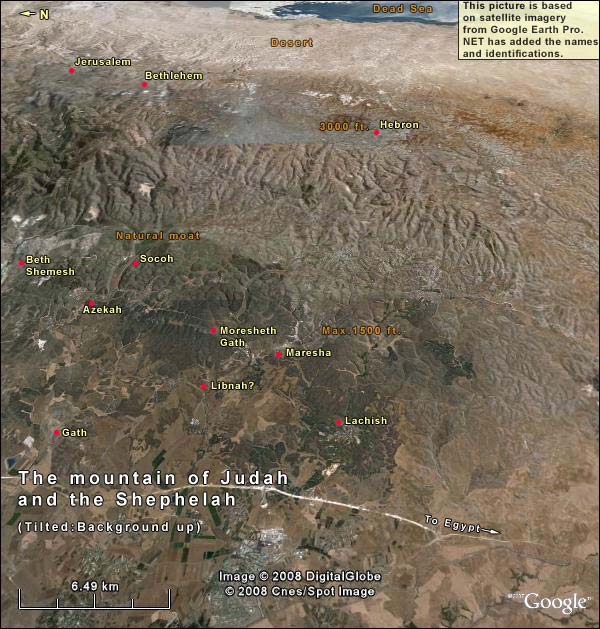

If we stand in the middle of Tell Maresha looking east, we behold the entire length of Judah's dark bulk, from Jerusalem to Hebron and beyond, as the mountain dips toward Beersheba. (Compass directions and distances.Jerusalem is 23 miles away at 58 degrees. Hebron is 13 miles away at 115 degrees. Beersheba is 25 miles away at 190 degrees.) We can see the strong line of separation between the mountain and the green hills of the Shephelah where we stand. Parting the two is a natural moat, formed by a series of north-south riverbeds such as Elah. Now add the fact that the block is bounded by a desert on the other, eastern side, and on the southern side by the Negev. From a military standpoint, what we are seeing is a landed peninsula. As long as it had defenders,In 163 BC the Seleucids were able to come up from the Shephelah via the southern part of the mountain, because it was held by their allies, the Idumeans. an army could attack it only from the north.

This character of "landed peninsula" has much to do with the fact that the Assyrians never conquered Jerusalem, making do with tribute instead. Of course there are other facts too: the mountain stood at no strategic location - it lay far from the Trunk Road to Egypt - and by the time the Assyrian army had taken more vital spots, such as Samaria (723 BC) or Lachish (701), its soldiers were probably battle-weary. (The Bible 2 Kings 19: 35-36. "It happened that night, that the angel of Yahweh went out, and struck one hundred eighty-five thousand in the camp of the Assyrians. When men arose early in the morning, behold, these were all dead bodies. So Sennacherib king of Assyria departed, and went and returned, and lived at Nineveh." mentions a plague that afflicted it.) Under these conditions, when an Assyrian king faced the still unconquered mountain, we can picture him thinking, "Hmmm, tribute will do."

Imagine what would have happened if the Assyrians had conquered all of Judah, including Jerusalem. The inhabitants would have fared as did the northern tribes: those allowed to live would have been deported and mixed with other populations, losing their national identity. In that case, who would have been left to preserve the texts that compose our First Testament? No one. (The Samaritans did not yet exist.) And so we would not have a First Testament, and without it, we wouldn't have the Gospels. This piece of geography helped make us who we are.

In 586 BC the Babylonians did take Jerusalem, coming from the north (cf. Jeremiah 1:14The word of Yahweh came to me the second time, saying, “What do you see?” I said, “I see a boiling caldron; and it is tipping away from the north.” Then Yahweh said to me, “Out of the north evil will break out on all the inhabitants of the land.). By that time, though, many key First Testament texts had crystallized. What is more, the Babylonians did not disperse the exiles. The Judahites and their descendants - now called Jews - assembled the First Testament.

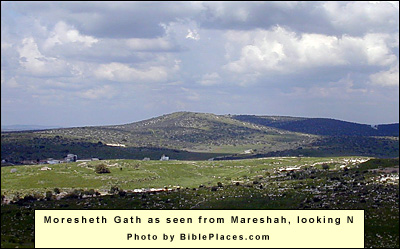

Removing our eyes from the mountain, we can find a number of Biblical sites nearby. Just 2.7 miles to the north (at 11 degrees) is Tell Goded, the Moresheth-Gath of Micah (Micah 1:1,The word of Yahweh that came to Micah the Morashtite in the days of Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, kings of Judah, which he saw concerning Samaria and Jerusalem. Jeremiah 26:18Micah the Morashtite prophesied in the days of Hezekiah king of Judah; and he spoke to all the people of Judah, saying, Thus says Yahweh of Armies: Zion shall be plowed as a field, and Jerusalem shall become heaps, and the mountain of the house as the high places of a forest. 26:19 Did Hezekiah king of Judah and all Judah put him to death? Didn’t he fear Yahweh, and entreat the favor of Yahweh, and Yahweh relented of the disaster which he had pronounced against them?). This city was paired with Maresha, during the periodNamely, 735-701 BC of the Assyrian invasions, as part of a chain protecting Judah's mountain and Jerusalem. (Compare the pairing of Socoh and Azekah in the Valley of Elah.)

To the left of Tell Goded, 3 miles from us, is Tell Burna (330 degrees). Here, some think, was Libnah, where Sennacherib fought after taking Lachish (2 Kings 19:8). This tell is outside the hill country, connecting directly to the coastal plain.

Almost on a line with Tell Burna, but farther way (8 miles from us at 340 degrees), is Gath, the town of Goliath (Tell Safit, a jutting, irregular shape beyond a grove of trees). Later built up by the Crusaders, who called it Blanchegarde, it rules the intersection of the Great Trunk Road and the Valley of Elah.

Wheeling due west, we can make out the chimneys of the power stations at AshdodThe tell of Ashdod is 19 miles from us at 306 degrees.and Ashkelon,Ashkelon is 21 miles away at 285 degreesonce major Philistine cities. As for Gaza, we have no landmark, but the city lies 33 miles from us at 255 degrees.

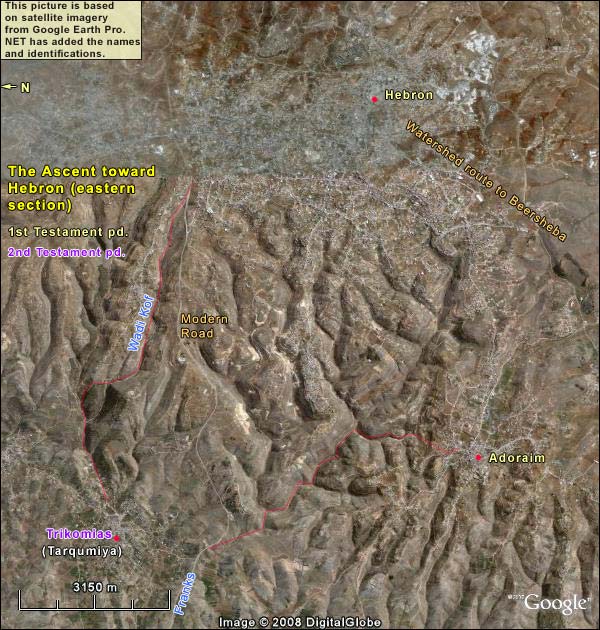

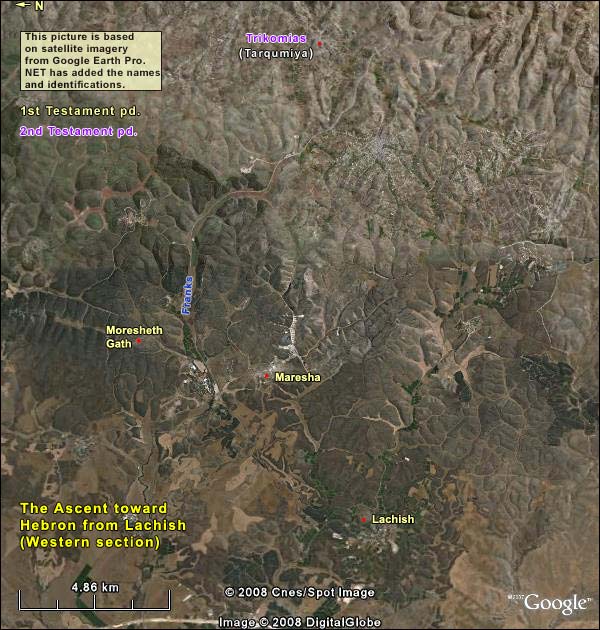

Closer in, we can make out just the top of Lachish, a flat brown stretch to the right of a farming community (3.5 miles away at 240 degrees). This brings us to the reason for Maresha's existence as a Judean fortress city. The southerly passage from the Great Trunk Road to Judah's mountain led through Lachish to Maresha, where we stand, and thence through a valleyCalled the Valley of the Franks, after the Crusaders, who had a fortress here and up to Adoraim and Hebron. Maresha and Moresheth-Gath were built to guard this passage. We show it in two satellite images, starting with the western portion:

What does it mean, however, to say that the Judean cities of the Shephelah had the function of protecting Jerusalem? How could they? Without major help from Egypt, they were sitting ducks. Sennacherib boasts he took 46 of them, and 1 Kings 18:13 admits he took "all the fortified cities of Judah." Their function may indeed have been to protect, but in the sense of wearing the enemy down, so that when he looked up again at the difficult mountain, he might think twice. These Shephelah cities were doomed in advance (Micah 1:13 -2:2):

To the chariot harness the team (rechesh), dweller of Lachish. You were the beginning of sin to the daughter of Zion; For in you were found the sins of Israel. Therefore you will give farewell gifts to Moreshethmoreshet means something given as an inheritance Gath. The houses of AchzibDeception will be a deceitful thing to the kings of Israel. I will yet bring your possessor (yoresh) to you, dweller of Mareshah. Unto (ad) Adullam he will come, Glory of Israel. Shave your heads, cut your hair for the children of your delight. Widen your baldness like a vulture, for they have been exiled from you!

{mospagebreak title=Maresha's history} Maresha's history

We have been standing on Tell Maresha (related to rosh, Hebrew for "head"), taking in the view, but except for the northwest corner,Two successive Hellenistic towers were found here on the remains of a Judahite structure. we see not a trace of archaeology around us. In fact the entire surface of the mound was exposed by British archaeologists in 1900, but their arrangement with the owner required that they re-cover it with soil.

The British found two Hellenistic strata from the 4th to the 1st centuries BC and, beneath them, remains of a city from the time of Judah, (Iron Age II Variously dated. Israelis use the broadest range: 1000 – 586 BC.). Amos Kloner, excavating the towers in the northwest corner in 1989 and 1991, also found items – but no structures – from the Persian period (538-332 BC). There have been no Canaanite finds. Unlike neighboring Moresheth-Gath, which had had a small Canaanite settlement, Maresha was just a bare hill until the Judahites built a city here as part of their western defensive belt around Jerusalem – an action attributed to Rehoboam2 Chronicles 11: 5-12 Rehoboam lived in Jerusalem and built up towns for defense in Judah: Bethlehem, Etam, Tekoa, Beth Zur, Soco, Adullam, Gath, Mareshah, Ziph, Adoraim, Lachish, Azekah, Zorah, Aijalon and Hebron. These were fortified cities in Judah and Benjamin. He strengthened their defenses and put commanders in them, with supplies of food, olive oil and wine. He put shields and spears in all the cities, and made them very strong. son of Solomon.

Asa, Rehoboam's grandson, is also said to have fortified the cities of Judah. 2 Chronicles (14: 9-12) reports a battle he fought near Maresha: There came out against them Zerah the Ethiopian with an army of a million troops, and three hundred chariots; and he came to Mareshah. Then Asa went out to meet him, and they set the battle in array in the valley of Zephathah at Mareshah. Asa cried to Yahweh his God, and said, “Yahweh, there is none besides you to help, between the mighty and him who has no strength. Help us, Yahweh our God; for we rely on you, and in your name are we come against this multitude. Yahweh, you are our God. Don’t let man prevail against you.” So Yahweh struck the Ethiopians before Asa, and before Judah; and the Ethiopians fled.

In 701, however, when the Assyrian swooped down, no miracle saved Maresha. We can be confident it was part of Hezekiah's revolt, because the British archaeologists found a likely sign of preparation: 17 seal impressions on jar handles with the words "For the King"Throughout the territory of Judah, archaeologists have discovered hundreds of jar handles bearing the inscription, "For the King" (lamelekh), followed by the name Hebron or Soco or Zif or Mamshit. All were made of the same kind of clay, probably in one place. Some bear the image of a scarab, others of the sun with wings. All date from Hezekiah's reign. The jars would have contained wine, grain and oil. These provisions would have been collected at the four named places, then packed in the jars and distributed. What was the purpose of this system? Many of the jar inscriptions included private names, and this may be a partial clue. It was the practice in Assyria to pay royal functionaries with wine and grain. Hezekiah perhaps copied this. That would explain why so many handles were found in the three cities of royal residence: Jerusalem, Ramat Rahel, and Lachish. When Hezekiah prepared his revolt against Assyria, he perhaps adapted this system in order to store provisions in the towns of Judah, for he knew they would be under siege. (la-melekh; some 37 were also found at Moresheth-Gath).

Maresha was surely among the 46 cities that Sennacherib boasted of taking. He would have deported the captives whom he let live. We have no indication whether King Josiah built it up again, as he did (in part) Lachish. In any event, when the Babylonians attacked Judah from the north in the early 6th century BC, the southern part of the country, from Adoraim near Hebron to Maresha and beyond, fell to the Edomites, who had long sought an opportunity.

The reaction of Jerusalem to this opportunism is reflected at the end of Psalm 137.

After Alexander the Great's conquests in 332, a colony of Phoenicians from Sidon – then allied to the GreeksThe Phoenicians sometimes supplied ships to the Persians – as in the late 4th century BC, when the Persians gave Dor and Jaffa to the king of Sidon. – settled here beside the Idumeans (Edomites).

The Idumean-Sidonian town must have been very small, for the next city here, after the Judean one, was Hellenistic.The Hellenistic period: 332 – 113 BC here, if we take the Hasmonean conquest as the start of a new era It was built in blocks ("insulae") with streets at right angles to each other (the Hippodamic system). This was the pattern not only on the 6-acre tell (now the acropolis), but also around it for 80 acres.

Compare Lachish, once the master of the southern Shephelah. In the Hellenistic period, Lachish had a temple but no city. Maresha was now the major urban center on the southern route between the Great Trunk Road and the mountain. Zenon,Zenon, assistant to the finance minister of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, King of Egypt from 281-246 BC. He wrote assiduously about his services to the minister as well as his own business ventures. Some 2000 of his documents were discovered in the late 19th century at the site of the ancient Egyptian village of Philadelphia.for instance, reported on a journey through Idumea in 259 BC, during which he bought slaves at Maresha.

In quarrying to build their houses, the Mareshans dug caves. These are what make the site breathtaking, and we shall treat them separately.See the Article Index above right

The main population was still Idumean in 113 BC when John Hyrcanus, a Hasmonean,The Hasmoneans: family of Judah Maccabee ("the hammer") and his brothers, who revolted successfully against the Greek Empire starting in 167 BC. They purified and re-dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem, establishing the festival of Hanukah ("dedication"). They ruled till 63 BC, and their domain extended almost as far as King David's. conquered Idumea for the Jewish state. "In many parts of the excavation," writes Kloner,Amos Kloner, "Maresha (Marisa):The Lower City," The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, Jerusalem, 1993, p. 953"it became clear that the lower city and its installations were damaged in the second half of the second century BCE. The lower city was apparently overcome by some major calamity and never resettled, except for a few caves. Later finds were extremely rare. Neither could any of the dozens of amphorae and Rhodian jar handles be dated any later." The calamity was almost certainly the work of John Hyrcanus.

Buried in the floor of a house, for instance, the excavators found a jug containing 25 silver coins, the latest of which was dated to the year 200 of the Seleucid era, that is, 113/112 BC. These were valuable, but their owner had been in no condition to retrieve them. The first floor of the house itself has been partly reconstructed (the rubble of a second was found in the ruins). From its courtyard, a staircase led down to caves that served as cisterns. The house and its caves can be visited.

Hyrcanus gave the Idumeans a choice: convert to Judaism or be gone! (Among those accepting conversion was the paternal grandfather of Herod the Great.) Since the Idumeans already practiced circumcision, their conversion may not have been very difficult. Nevertheless, inscriptions show that precisely at this time Idumean names became plentiful in Egypt.

When Pompey took the land for Rome in 63 BC, he tore the formerly Greek cities, including Maresha, away from Jewish sovereignty. A few years later Gabinius, proconsul of Syria, rebuilt them, but the new Maresha never spread beyond the tell.

The whole of Idumea was shifted to the hands of Herod in 40 BC. That was the year when his enemy, the Parthians, temporarily got the upper hand. After looting Jerusalem, they swept down into the Shephelah and wiped Maresha off the map. No other city was so diligently destroyed, raising the possibility that it had a special importance for Herod (his birthplace?).

The location was too crucial to remain abandoned. Soon a new town sprang up nearby. This was Beit Guvrin, destined to become one of the land's six "excellent" cities. We shall treat it separately.See Article Index above.

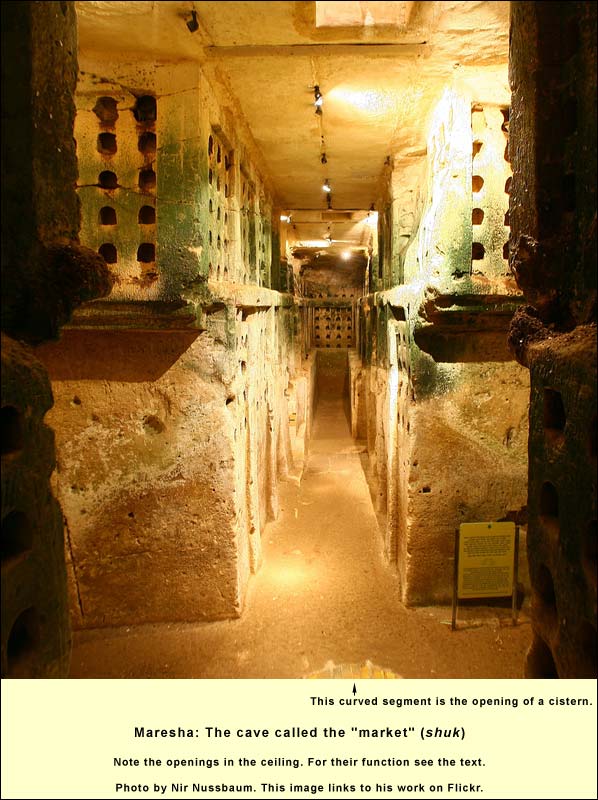

{mospagebreak title="Market" cave} The "Market" Cave In the 3d century BC, when the people of Maresha planned houses in the area around the acropolis (tell), they first dug directly beneath their future floors for the building stones, chiseling out each layer at brick height. They were able to do this without great expense because the stone that covers the Shephelah has peculiar qualities. It is a relatively softArchaeologist Amos Kloner put some people to work and found that they could quarry, per hour, a piece of stone measuring one meter long, 60 cm. high and 60 cm wide. We can stick our thumbnails into it. chalk deposited at the bottom of the sea that once covered this country, in a period geologists call the Eocene. There are almost no intruding layers of flint (such as abound in the desert east of the mountain), and so people could dig caves without interruption. They dug thousands throughout the Shephelah.

On the surface a brittle crust developed, one to two yards thick, called nari.The nari may have formed as follows: during the winter rains, water quickly percolated into the porous chalk. In the long hot summer, as the surface dried out, the moisture below the surface rose, carrying dissolved minerals from the lower layers up with it. Evaporating, the moisture left these minerals behind. Added to the calcium carbonate already in the surface stone, these minerals formed a dense, less porous, brittle layer, effectively sealing the moist stone below and impeding further percolation from above. The quarriers made a small hole in the nari until they reached the thick layer of chalk below. Here they chiseled in an ever widening bell-shape, leaving vaults to prevent collapse. The nari hole was kept small so that the stone beneath would retain its moist, soft quality.

There are 153 cave-networks around Maresha. Many caves served as cisterns in this spring-poor region, others as columbaria (dovecotes), chambers for olive-pressing, and tombs. Caves elsewhere in the Shephelah may also have served as places to conceal wealth from the tax man, and earlier – during the Bar Kokhba revolt – as hideouts from which one could attack occupying soldiers and disappear into the earth.

At Maresha the most striking cave is the so-called "market" (shuk). There are just a few traces of the house to which it belonged, but we descend, turn a corner, and are confronted with this:

The first question to arise is usually: What were all the niches for? There are almost 2000 of them in this cave. In Rome, urns with ashes of the dead were placed in niches, but no trace of such has been found here. Besides, cremation is not attested in the literary sources for the land. And they would have been very small urns – each niche is only about 9 inches wide by 10 deep.

Some think the cave was a columbarium – a place to raise doves. These were valued in the ancient world, both for the excellent fertilizer they produce and as a good source of protein. (Lacking refrigeration, people slaughtered a four-legged beast only when lots of diners were on hand; small sources of protein like doves and fish were crucial for the everyday diet.) In nature, rock doves (pigeons) nest in cliff sides or caves. The theory for this cave goes as follows: the owners opened the small holes in the ceiling (there are two in the photo above), threw in some young doves that hadn't yet mated, added grain and nest-building materials, then closed the holes. Within a month or so, mating occurred and nests were built in the niches. Then the holes in the ceiling could be opened, and the birds would remain. The males flew out each day to gather grain and seed in the fields, bringing these back to their females and offspring in the cave. Thus the columbarium became self-sufficient.

To build and maintain a columbarium with 2000 niches would have cost much more than to dig it out of the soft limestone.

The pigeons would not ordinarily have sat in the niches, rather on crossbeams. Regularly the owners would have come in and removed their valuable excrement. We see no niches in the lower portion – the idea was to keep the nests high enough off the floor that predators, such as snakes, could not get at the younglings. Note too, in the photo above, that the first opening in the ceiling is located above a cistern in the floor: doves must drink to digest their seeds and grain.

So many things fit together that the columbarium theory seems irresistible. Yet, reports Kloner, mineralogical and chemical analyses detected no traces of dove excrement in soil samples. One might explain this absence by noting the brevity of the dove business at Maresha; it seems to have ended for some reason after only half a century. The cave was then put to other uses. Accumulated bones of goats, pigs and sheep were found. Some of the niches contained ceramic bowls. Numerous sherds, dating from the 3d to the mid-1st centuries BC, were heaped in the corridors. The former columbaria were variously used, it seems, as stables, bathhouses, ritual halls, and storerooms.

Some 50 pigeons live in the "market" today. About 60 caves of this type have been found at Maresha, with a total of roughly 50,000 niches. {mospagebreak title=Olive cave} Cave Complex with Olive Press

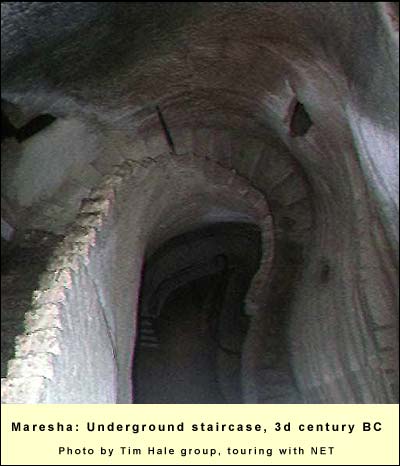

Few of the 153 cave complexes are open for visits. Of these the most remarkable is on the tell's south side. Above ground we see the remains of houses made of the brick-like stones that were quarried below. A staircase leads past a bath into a cistern, and thus begins a winding journey through cave after cave, mainly "columbaria" and cisterns, up and down staircases carved from the chalk 300 years before the birth of Jesus.

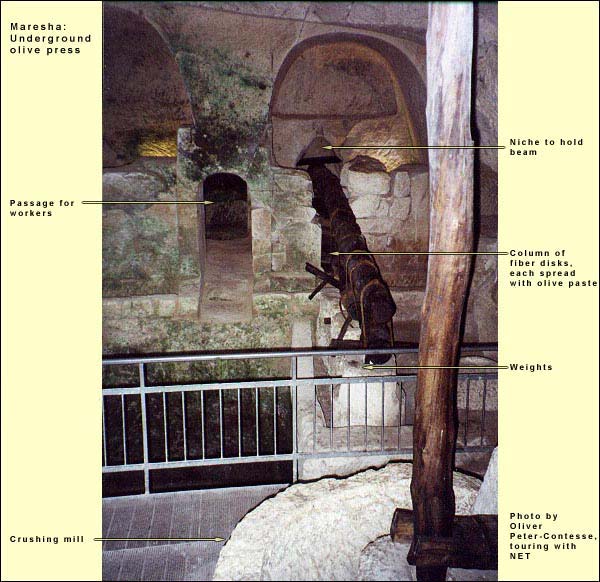

The last cave in this magical journey was an olive-oil factory. Olive presses are normally above ground, but 17 have been found beneath the surface of Hellenistic Maresha. It was relatively easy to carve out a chamber, and because of the long waiting periods during the pressing (discussed below), it was convenient to have the assemblage under the house rather than outside the city.

Olive oil was big business in the Shephelah.In nearby Ekron, for instance, more than 100 presses have been found. Just down the road lay Egypt, whose heat is not conducive to growing olives. The Egyptians liked night life. There could be no night life without olive oil to fuel lamps. (Other uses. Olive oil was also used in food, in religious ceremonies, as medicine, in cleaning the body, and for anointing the male physique at Hellenistic gyms.)

Let us assume a population of 5000 for Hellenistic Maresha. Suppose there were 30 olive presses (13 more than found so far). Each press would have handled 15 acres of olive trees, each acre producing 600 kg. of oil. The total annual olive oil production, then, would have been 300,000 liters. Figuring that each person consumed 18 liters per annum, 90,000 liters would have been used by the Mareshans themselves, leaving 210,000 liters for export to Egypt.

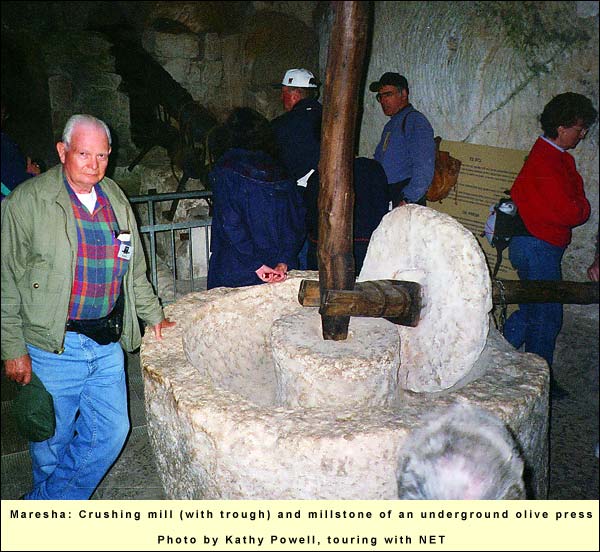

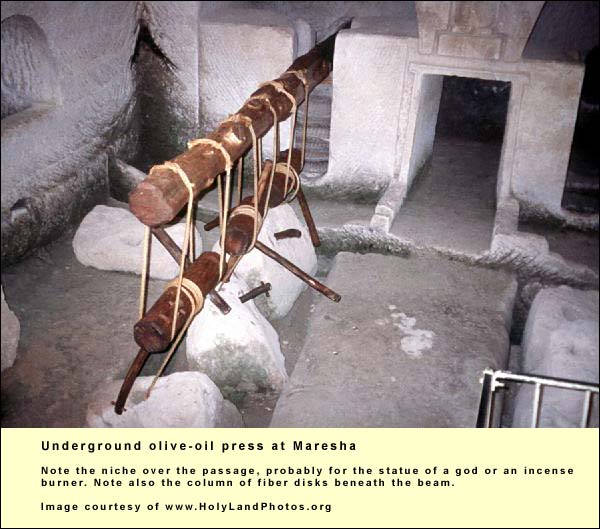

Production occurred in two stages, both of which are illustrated in this cave. First, after washing the olives, one placed them in a circular stone trough called a crushing mill and wheeled a millstone over them for half an hour. The olives need to be thoroughly crushed in order for large oil drops to form, and in order for the fruit enzymes to produce the desired aroma and taste. Then the top layer is skimmed off. This is the best oil, for use in ceremony and with food.

A second stage begins. The paste is scooped from the trough and spread on the surfaces of fiber disks. These are heaped in a column on which pressure is then exerted. In the photographs you can see the method that was used at Maresha. A large wooden beam (reconstructed) was placed over the column of disks, its end held by a niche in the wall. A stone weight (330-550 lbs.) was then hung from the beam, giving about 3 tons of pressure. Liquid percolated through the pores of the fiber disks into a basin below. After separation, which took an hour or so, the top 70% was oil, the next 27% water and the rest sediments. The workers scooped out the oil, discarded the rest, and then hung a second weight from the beam, etc. The heavier the pressure, the lower the quality. The last batch was used for ordinary lamps.

All this took place during the olive harvest in October and November. Too green, the olives gave a bitter oil, too ripe, a rancid. The process was delicate and difficult. One wanted divine protection. Over the gateway in another of the Maresha oil presses (below) appears a niche – probably occupied by the statue of a deity or an incense burner.

{mospagebreak title=Burial caves} Burial caves

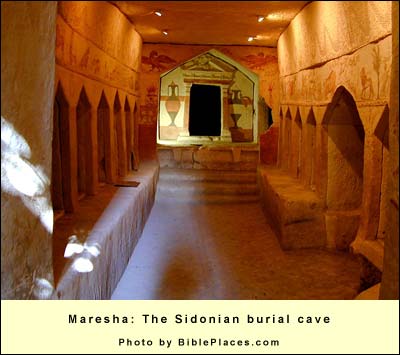

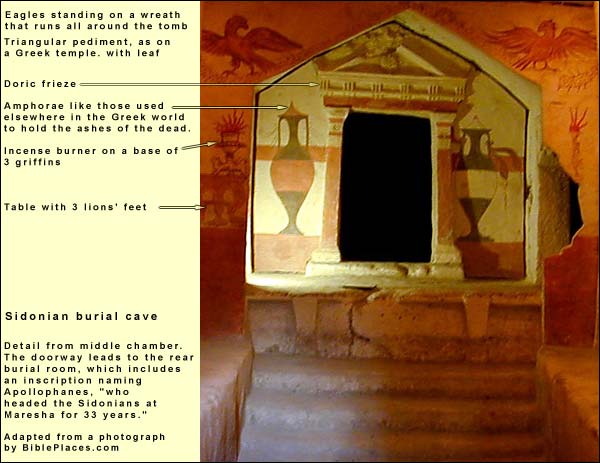

The Egyptian connection went beyond olive oil to the grave. Sixty underground tomb complexes, all from the 3d and 2d centuries BC, have been found around the lower city of Maresha. The most striking of these lies just southeast of the tell. It contains forms and motifs that seem transplanted from Hellenistic tombs in Alexandria. Over one of its chambers, the British archaeologists found the following inscription (now vanished):

"Apollophanes, son of Sesmaios, who headed the Sidonians at Maresha for 33 years. He was treasured as the best and as one who loved his kindred exceedingly. He died after living 74 years."

This inscription, by the way, is a rare piece of direct evidenceThere is also a Roman-Byzantine ruin one kilometer west of the tell, called the ruin of Merasch.that the city was Maresha. For the name has not been preserved in that of the tell, which was called by the local Arab population Sand'hanneh.The reason may be seen just east of the tell and north of this tomb: there stands the lone apse of a Byzantine basilica, which the Crusaders incorporated into a Church of Saint Anne.

From the words about Apollophanes, it seems the cave served descendants of the Sidonian colony. Its 30 inscriptions and 5 graffiti indicate that the fathers generally bore Semitic names, as did the Phoenicians of Sidon, but they gave Greek names to their sons. Some of these Sidonian descendants, however, had Idumean (Edomite) names, indicating assimilation to the main part of Maresha's population.

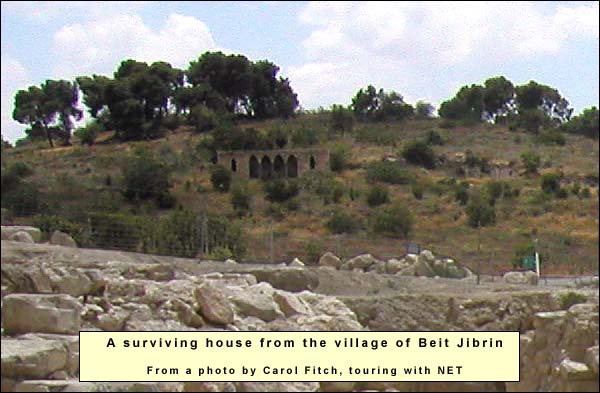

Shortly after the tombs of Maresha were discovered in 1902, iconoclasts from the nearby village of Beit Jibrin eradicated the faces of any human images they saw. The archaeologists rushed back and made copies of all that remained. These became the basis for the reconstruction, on metal sheets attached to the rock, that we see today in the middle chamber of the Sidonian tomb. On the right door jamb, as we enter, is Cerberus, the three-headed dog that guarded the entrance to the Greek underworld. In the middle chamber are seven gabled openings, loculi, on either side. (The whole cave has 41 of these.) The corpse was laid in a loculus, and this was sealed. When all loculi were filled and a new death occurred in the extended family, a loculus was opened (preferably one that had been sealed for at least a year) and the bones were removed to another loculus, which served as a repository for many.

The evidence is for burial, not cremation, but at the far end of the tomb, flanking the entrance into the more elite chambers, are two amphorae such as the Greeks had long used for the ashes of the dead. Thus the Greek influence came through, despite the difference in custom. Its immediate source was Alexandria, whose architecture inspired the same motifs on the tombs of Petra during this period – see, for a supreme instance, the "Treasury" there.

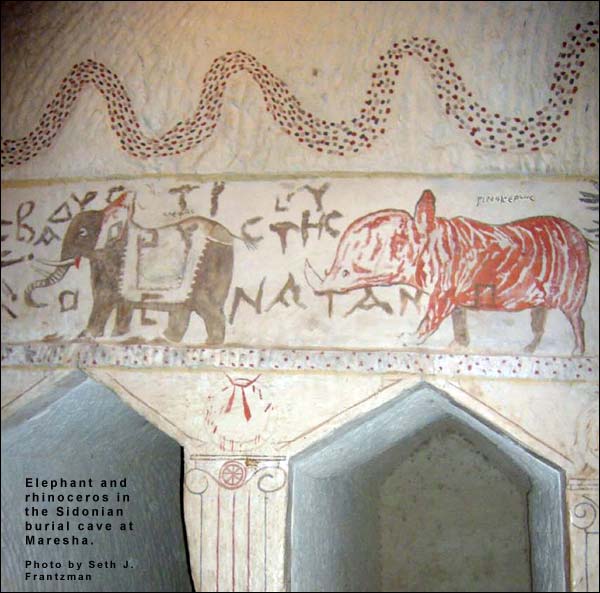

In this middle chamber, above the gables of the loculi, are pictures of animals, including (on the right as you enter) a leopard, a lion, a snake, a giraffe (designated here as a camel-panther), a wild boar, a griffin (legendary), an oryx, a rhinoceros, an elephant, and a figure representing Africa. In the northwest corner are two fishes, one with an elephant trunk while the other has a large head with a snout like a rhinoceros. More animals follow. "The animal frieze," writes Kloner,Amos Kloner, "Maresha (Marisa):The Lower City," The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, Jerusalem, 1993, pp. 955-56"is undoubtedly influenced by the Ptolemaic menagerie drawings, which are known to have existed in Alexandria in the Hellenistic period. Under Aristotle's influence, there was much popular interest in the natural sciences at that time. From descriptions of the menagerie of Ptolemaeus II…we know that it included lions, leopards, other felines, rodents, buffaloes from India and Africa, a wild ass from Moab, large snakes, a giraffe, a rhinoceros, and various birds – these are in fact some of the very animals represented at Marisa. … The fishes with elephant face and rhinoceros face are taken from the legends based on the belief of Greek scholars that an exact correspondence existed between land and marine animals. …The animal frieze at Mareshah is a unique document of its kind in the Hellenistic world. Only Roman mosaics show influences from the Hellenistic-Egyptian sources from which the artist at Marisa drew his inspiration."

The Sidonian cave is famous for one particular graffito. Found on the right of the entrance to the middle chamber, it seems to be a note left by someone making an illicit appointment. One possible translation goes as follows: "I can neither suffer anything for you nor give you any pleasure. I lie with another, although I love you. But truly, by Aphrodite, I am exceedingly glad that your cloak lies as security. Don't knock on the wall. That makes noise. Rather [give a sign] through the door with a nod. Arranged!"

A few yards south we can visit another burial cave, called the Tomb of the Musicians: it includes a male flautist and female harpist descending a slope – apparently to the realm of the dead. {mospagebreak title=Beit Guvrin} Beit Guvrin/Eleutheropolis

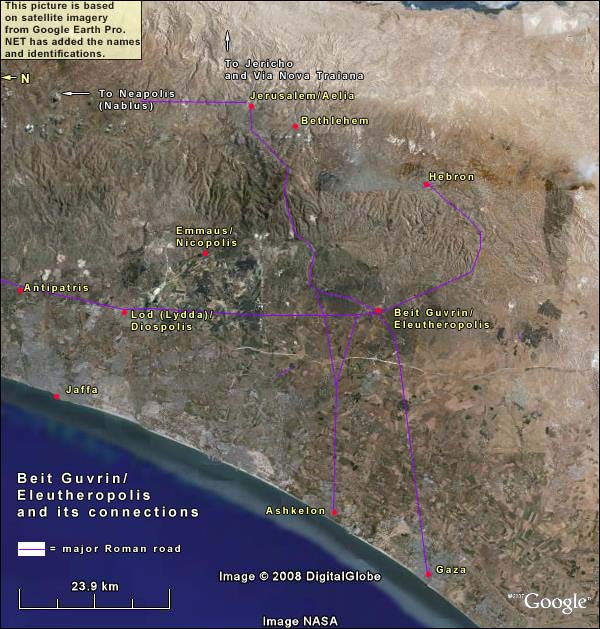

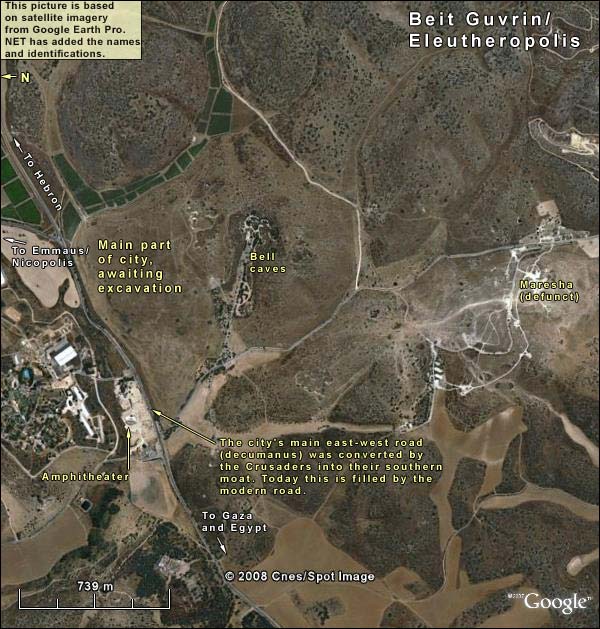

After the destruction of Maresha by the Parthians in 40 BC, this strategic spot – on the crossroads joining Gaza, Ashkelon, Lydda, Hebron, and Jerusalem – was bound to be repopulated. By the 1st century AD, a village named Beit Guvrin had risen less than a mile from the ruin of Maresha, sitting smack on the junction.

Why the name "Beit Guvrin"? No one can be sure. In Hebrew the words mean Place of Men or Heroes – and this can be extended to Giants. Perhaps the tremendous height of the many abandoned caves suggested that giants had once lived in them.

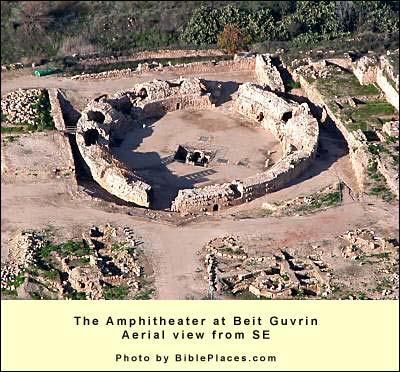

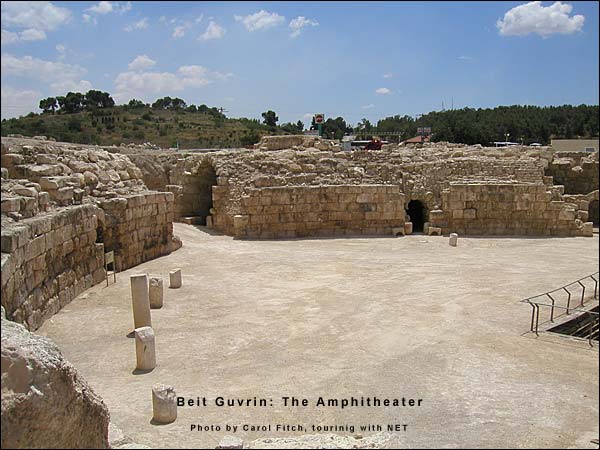

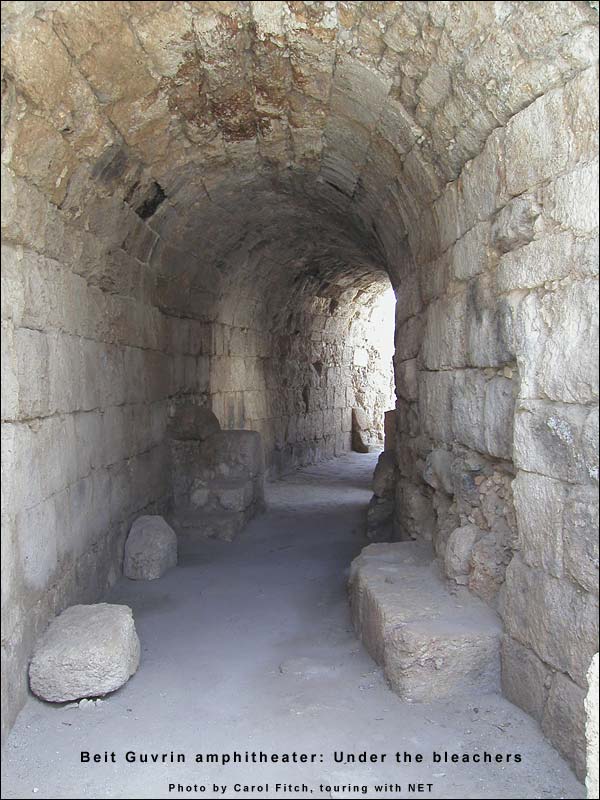

The Shephelah played a major role in the Bar Kokhba revolt. After quelling it, Hadrian probably stationed a legion here. Indirect evidence is the amphitheater,An oval or circular theater in which the spectators sat on both {amphi-) sides built on the northwest fringe of the city in the 2nd century AD.

Amphitheaters were intended for the bloodiest spectacles. In the Roman provinces, we find them only at places where the army was stationed. After the revolts against Rome in this land, they appeared at Scythopolis, Neapolis, Caesarea Maritima and here. The first three were adapted from hippodromes. Only the one at Beit Guvrin was originally built as an amphitheater. It is the best example in the country.

The closest survival in today's world is the bull ring, but even that is a step removed, because the ancient audience entered the amphitheater knowing that they were about to watch human beings die violent deaths. In a famous passage from his Confessions (VI 8), Augustine describes what happened to a friend who went to Rome:

"He, not relinquishing that worldly way which his parents had bewitched him to pursue, had gone before me to Rome, to study law, and there he was carried away in an extraordinary manner with an incredible eagerness after the gladiatorial shows. For, being utterly opposed to and detesting such spectacles, he was one day met by chance by various of his acquaintance and fellow-students returning from dinner, and they with a friendly violence drew him, vehemently objecting and resisting, into the amphitheatre, on a day of these cruel and deadly shows, he thus protesting: Though you drag my body to that place, and there place me, can you force me to give my mind and lend my eyes to these shows? Thus shall I be absent while present, and so shall overcome both you and them. They hearing this, dragged him on nevertheless, desirous, perchance, to see whether he could do as he said. When they had arrived thither, and had taken their places as they could, the whole place became excited with the inhuman sports. But he, shutting up the doors of his eyes, forbade his mind to roam abroad after such naughtiness; and would that he had shut his ears also! For, upon the fall of one in the fight, a mighty cry from the whole audience stirring him strongly, he, overcome by curiosity, and prepared as it were to despise and rise superior to it, no matter what it were, opened his eyes, and was struck with a deeper wound in his soul than the other, whom he desired to see, was in his body; and he fell more miserably than he on whose fall that mighty clamour was raised, which entered through his ears, and unlocked his eyes, to make way for the striking and beating down of his soul, which was bold rather than valiant hitherto; and so much the weaker in that it presumed on itself, which ought to have depended on You. For, directly he saw that blood, he therewith imbibed a sort of savageness; nor did he turn away, but fixed his eye, drinking in madness unconsciously, and was delighted with the guilty contest, and drunken with the bloody pastime. Nor was he now the same he came in, but was one of the throng he came unto, and a true companion of those who had brought him thither. Why need I say more? He looked, shouted, was excited, carried away with him the madness which would stimulate him to return, not only with those who first enticed him, but also before them, yea, and to draw in others." (Translated by J.G. Pilkington.)

Such spectacles aroused the sex drive. Prostitutes waited outside the arena to make another kind of killing.

When the show was over, the crowds streamed out through gates called vomitaria, so named because they appeared to be puking the people out. There were up to 14 rows of seats, the lowest just above the reach of the leaping lion. Underground tunnels led to a hole in the center of the arenaArena means sand in Greek: the floor consisted of sand to absorb the blood. (see the last two pictures above) – perhaps the beasts emerged into light there. Beneath the bleachers is a hall where the gladiators waited their turns. For a chilling reconstruction of a moment beneath the stands, see Livia's speech to the gladiators in the TV series I Claudius, based on Robert Graves' historical novel of that name.

In 200 AD, the Roman emperor Septimius Severus made a journey through the land, distributing gifts to his hosts in the form of new rights and privileges. On Beit Guvrin he conferred the ius italicumAn honor given by Roman emperors to certain cities outside Italy, treating them as if they were on Italian soil. They were governed under Roman law, had a degree of autonomy in relation to provincial governors, and those born in the city automatically received Roman citizenship., renaming it Eleutheropolis, "city of freedom" or "city of free men."Othmar Keel (Orte und Landschaften der Bibel, II, p. 856) suggests that the name Eleutheropolis too may have derived from the many caves – that is, holes – in the neighborhood. In Hebrew the word for holes is horim, but this is also plural for "free." Keel mentions the additional possibility that the local Idumeans – the Edomites of the First Testament – were identified with their ancestors, the Horites (Genesis 14:6). The Edomites had lived east of the Dead Sea in earlier times, but the Idumeans were now living here. It was natural to think that the Horites had lived here too. Then Horites could have been associated with horim, free men. Eleutheropolis had more territory under its jurisdiction than any other city in the land. It was bigger than Jerusalem. A 4th-century historian, Ammianus Marcellinus,Res Gestium, XIV, 8: 11-2numbers it among the country's "Five Cities of Excellence."

The built-up urban area amounted to 163 acres. So large a town required much water. The Shephelah gets 17 inches of rain per year, but the rock surface (nari,The nari may have formed as follows: during the winter rains, water quickly percolated into the porous chalk. In the long hot summer, as the surface dried out, the moisture below the surface rose, carrying dissolved minerals from the lower layers up with it. Evaporating, the moisture left these minerals behind. Added to the calcium carbonate already in the surface stone, these minerals formed a dense, less porous, brittle layer, effectively sealing the moist stone below and impeding further percolation from above.) prevents percolation, so springs are scarce. Most of the Hellenistic cisterns were probably out of use, although the inhabitants dug new ones. In addition there was the typical Roman solution: aqueducts. Eleutheropolis had at least two. A duct 15 miles long came from the vicinity of Hebron. A second, not 2 miles long, came from Tel Goded (Moresheth Gath). Near it is a well, though it is lower than the duct. The operators may have used a kind of wheel, like a small Ferris wheel with buckets attached, each of which in its turn lifted water from the well and poured it into the duct.

Only a small northern extension of the Roman city has been excavated, including the amphitheater and a bathhouse. The large hill south of the modern road contains the ruins of Eleutheropolis. Looking at Scythopolis or Gerasa, one can imagine what splendor may be waiting here.

In the 8th book of his Church History, Eusebius records the names of Christian martyrs – "our Savior's athletes" – including three from the Shephelah. One was Zebinas of Eleutheropolis. Around 310 AD, when Emperor Maximinus renewed the decrees against Christians, Zebinas stepped forward with two co-believers and boldly preached to the Roman governor of Palaestina, who was in the act of making a pagan sacrifice. The governor had them executed.

By 325 AD, Christianity was legal, and Eleutheropolis had become a bishopric, represented at the Council at Nicaea.It passed the Nicaean Creed, attempting to resolve doctrinal differences on the status of Jesus that threatened to sunder the early church. We know from the Talmud that there was also a Jewish community here, including scholars.

Its position on the Gaza-Jerusalem road ensured the city's survival through the ages. After the Arab conquest (636-640 AD), the inhabitants reverted to a version of the name Beit Guvrin: Beit Jibrin. Its quarries, known as the Bell Caves, were then at the height of production, no doubt enriching the area. The head of the conquering Rashid army chose to live in Beit Jibrin. Christian influence must have remained strong, however, for in 796 an anti-Christian Bedouin group destroyed the town.

It recovered. Two centuries later, we have this descriptionQuoted in Guy Le Strange, Palestine Under the Moslems, 1890, p. 412 from the Muslim geographer, al-Muqaddasi:

"[Beit Jibrin] is a city partly in the hill country, partly in the plain. …[T]here are here marble [sic] quarries. The district sends its produce to the capital [Ramla]. It is an emporium for the neighbouring country, and a land of riches and plenty, possessing fine domains. The population, however, is now on the decrease and impotence possesses the men." Despite the Crusader conquest in 1099, the Muslims managed to hold Ashkelon, from which they made attacks on the Shephelah. In order to check them, the Crusaders circled that city with a ring of castles , starting with Beit Jibrin (which they thought was Beersheba). They dug the southern moat where the modern road is (and where a major east-west road of Eleutheropolis had run). The fort was finished in 1136. In 1153 a triapsidal church was built up against it. Three restored arches of the church's north end catch the eye as one enters the site.

In 1153 Ashkelon fell to the Crusaders. The strategic value of Beit Jibrin declined. Nevertheless, writes BenvenistiMeron Benvenisti, The Crusaders in the Holy Land, Jerusalem, Israel Universities Press, 1970 (p. 186), "it continued to be an important crossroads where, according to a Moslem traveler of the time, taxes were levied on passing caravans."

During the War of 1948, Palestinian refugees from Jaffa took shelter in the bell caves. Six months later, in October, the town's strategic position attracted the attention of Israel's army. The Jaffan refugees moved again, this time toward Hebron, joined by Beit Jibrin's 2000 villagers. Kibbutz Beit Guvrin arose near the site in 1949.

{mospagebreak title=Bell Caves}

Bell caves

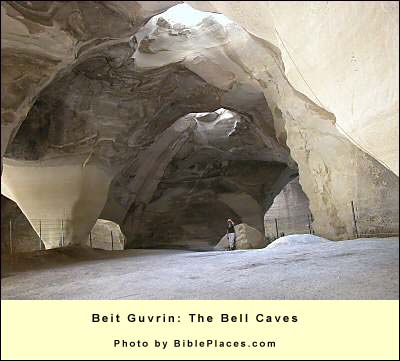

Until the 1990s, the main attraction of Beit Guvrin was a series of caves whose vaulted heights lift the visitor's spirit as in a cathedral. They were quarries.

Starting perhaps in the late Roman period and continuing through the 10th century, people removed the soft limestone here, burning it to get lime for cement. Yehoshua Ben Arieh,Israel Exploration Journal, 12, 1962, pp. 47-61) who studied these caves, found heavy use of cement in the former Arab houses of the Shephelah. There was also much use in the ancient coastal cities. For instance, Ashkelon's Roman-Byzantine city wall had a huge amount (Keel,Othmar Keel, Max Kuechler and Christoph Uehlinger, Orte und Landschaften der Bibel, Koeln: Benziger and Goettingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1984, Volume II p. 868). By contrast, people on the mountain of Judah preferred to build dry, using well cut stones, as in the mighty retaining walls of Herod's temple-enclosure.

The Beit Guvrin quarriers started from the surface. They dug a meter-wide cylinder through the brittle crust of the nari.The nari may have formed as follows: during the winter rains, water quickly percolated into the porous chalk. In the long hot summer, as the surface dried out, the moisture below the surface rose, carrying dissolved minerals from the lower layers up with it. Evaporating, the moisture left these minerals behind. Added to the calcium carbonate already in the surface stone, these minerals formed a dense, less porous, brittle layer, effectively sealing the moist stone below and impeding further percolation from above. It was important to keep this opening small, so that the underlying chalk would not become nari itself – rather, remain soft and moist.

After a yard or two, the quarriers reached it. Here they began chiseling downward and outward, leaving enough of a vault to support the upper surface against collapse. They quarried chunks of 10 – 14 pounds each. These could be transported to the building sites or burned right here. (Beside most of these caves, traces of kilns were found.) The burning of limestone required much wood. No doubt it was a factor in the land's deforestation.

Sometimes the quarriers chiseled a figure or an inscription, which can with luck be discerned today from below. Among the symbols are crosses.These gave rise to the notion that Christians sought refuge here during times of persecution. The records do not indicate, however, that Christians tried to avoid martyrdom. As the cave deepened, it took the shape of a bell. When very deep, an alternative entrance would be made from the side.

There are at least 800 of these quarry caves within a two-mile radius of Beit Guvrin, and about 3000 in the Shephelah as a whole.

{mospagebreak title=Logistics} Logistics

Beit Guvrin/Maresha is a National Park. Hours: April – September: 0800 – 1700 October – March: 0800 – 1600 On Fridays and eves of Jewish holidays, the site closes one hour earlier. Arrive at least an hour before closing time.

Phones: 08 681 1020

Best time to visit: February or March, when the wildflowers are at their peak. Equipment: There are electric lights in the caves, but it is a good idea to bring flashlights just in case. Outdoors there is no shade, so take a hat and water. Good walking shoes are a must.