Emmaus

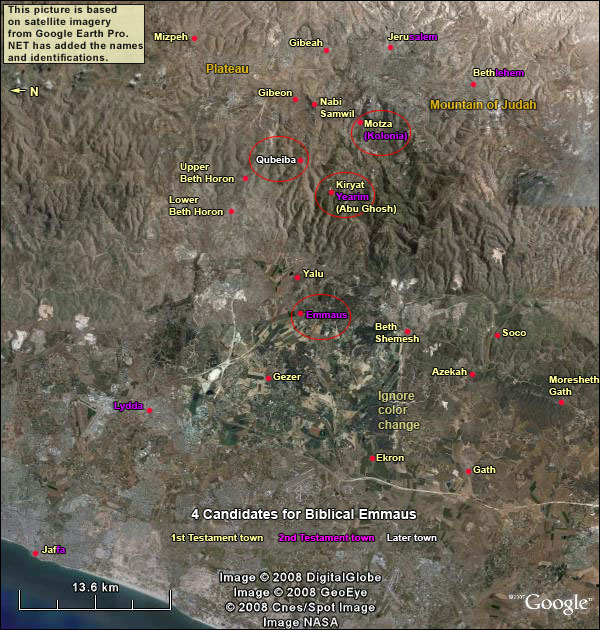

The two tell the third how their hopes have been dashed. Jesus, whom they had thought to be the Messiah, was crucified three days earlier. They mention reports of his having risen from death, but these are mere rumors. After reaching Emmaus, they invite the stranger to eat with them. When he breaks the bread, they recognize Jesus. They return to Jerusalem and report this to the eleven. Soon Jesus appears and greets the assembled disciples. The location of Luke's Emmaus is a puzzle. Until the War of 1967, an Arab village named Imwas stood in the Valley of Ayalon, at a strategic point on the southernmost ancient link road between the international highways. "Imwas" preserved the name "Emmaus." Ancient references fit the location of Imwas. For example, 1 Maccabees 3:40 says of the Seleucid army, which in 165 BC was trying to defeat the rebellious Maccabees in the highlands: "Setting out with all their forces, they came and pitched their camp near Emmaus in the plain." Emmaus-Imwas stood indeed on a slight rise above a plain, for the Valley of Ayalon is broad at this point. The place controlled three routes up to the highlands near Jerusalem, including the best for an army: the Beth Horon ridge, This was the only ridge in the area that was not broken by a wadi.

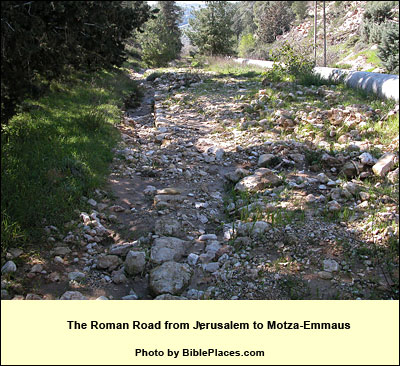

This Emmaus-Beth Horon route was the northernmost part of a system that is replicated southward through the Shephelah. The pattern is as follows. Starting from a city or cities on the coastal trunk road, a broad valley leads eastward to a point where there begins a narrow ascent to the central mountain range. If we confine ourselves to the northernmost part of this system in the Greek and Roman periods, three cities on the coastal road connected to the Valley of Ayalon: Jaffa (Joppa), Lydda and Antipatris. Emmaus stood at the transitional point. From it one climbed the Beth Horon ridge to the plateau lying north of Jerusalem.

Yet here's the rub: this Emmaus was 160 stadia from Jerusalem, about 22 Roman miles. (A stadium is 582 feet.) That's three times the distance given in Luke!

The only other Emmaus we hear about in ancient sources, in a lone mention by Josephus, was up in the mountain, a mere 30 stadia (3.5 miles) from Jerusalem. That's half the distance in Luke. Nearby was a village called Motza, where the Jews of Jerusalem would gather willow fronds for the Feast of Tabernacles (Mishnah, Sukka 4:5).

Here, wrote JosephusJosephus Flavius (36 – 100 AD), Jewish general, one of two directing the revolt against Rome in Galilee. After Vespasian captured him, he prophesied the latter would be emperor. When this proved true, the Romans honored him. He then turned historian, writing The Jewish War, The Antiquities of the Jews and many other books. Because of a paragraph about John the Baptist (and maybe a sentence about Jesus), the Church preserved his works. (War VII 230), the Roman Emperor Vespasian settled 800 veterans after putting down the first great Jewish revolt. The name of Motza-Emmaus then changed to kolonia. (The Arab village of Kolonia stood until 1948.) In antiquity, this change in nomenclature left only one place called Emmaus: the too-distant city in the Valley of Ayalon.

All other mentions of Emmaus in the ancient sources, except Luke, fit the Ayalon Emmaus, site of the later Imwas. We know from Josephus that a band of Jews attacked a Roman cohort at Emmaus in 4 BC, on the occasion of Herod's death, and the town was burned by the Romans as punishment. A Roman legion spent two years there before marching up to take Jerusalem from the Jewish rebels in 70 AD.

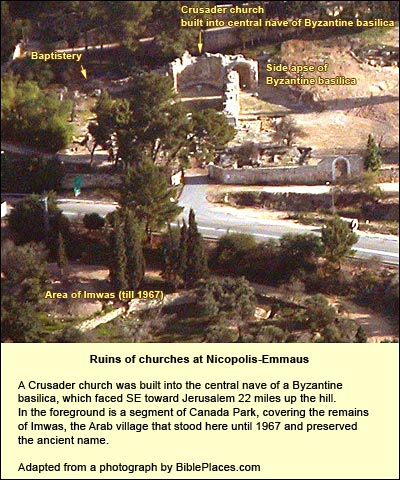

The great theologian OrigenOrigen (ca. 185-254 AD). A Christian thinker, the greatest to appear after Paul, who thought through the Christian faith from what he called "First Principles." He did most of his work at Caesarea Maritima. favored identifying the Ayalon Emmaus with the village mentioned in Luke. By that time it had long been the only location called Emmaus (except for a town on the far-away Lake of Galilee). In 221 the city sent a friend of Origen's, Julius Africanus, with a delegation to the Roman emperor. Africanus asked permission to rebuild Emmaus as a new entity with the rights of a Roman city and a new name: Nicopolis, City of Victory. The delegation succeeded. Eusebius,Eusebius (ca. 263-339 AD), Bishop of Caesarea Maritima,was a historian of the early Christian church at the time of Constantine. in his Book of Names (Onomasticon 90:15), reported that Luke's Emmaus "is now Nicopolis, a famous city of Palestine." JeromeJerome (a.k.a. Hieronymus) (ca. 347 – 420 AD), the learned Church father (and favorite saint of Christian painters after the Holy Family), spent the last 34 years of his life in Bethlehem, where he translated both the Hebrew First Testament and the Greek Second Testament into Latin, the so-called "Vulgate." It remained the authoritative version of the Bible for Western Christendom for a thousand years. He took part in the great theological controversies of his day, and his influence was tremendous. From what remains of his vast correspondence, he appears to have kept his faith at the cost of struggle with his own impulses; his bitter, combative disposition (perhaps a result of that struggle) often seems far from the teachings of tolerance found in Jesus, Paul and Origen. concurred.

Eusebius, Jerome and other ByzantinesThe Byzantine period – that is, the period of the Eastern Christian Roman Empire –may be dated from 330 AD, when Constantine re-named the city of Byzantium "Constantinople" and dedicated it to the God of the Christians. Its end, in this land, came in 638, when the Muslims took Jerusalem. Elsewhere it lasted much longer: Constantinople finally fell to the Turks in 1453. found no problem in the distance from Jerusalem. A local scribe (Origen himself?) had changed the figure in Luke from 60 to 160. (The change appears in a few ancient manuscripts, but these are not considered the best.) The scribe, who knew but the one Emmaus, probably thought that the 100 had been dropped by mistake. The Byzantines, known for their stamina (they could stand five hours straight through each worship service), could envision Cleopas and his companion, accompanied by the third man, descending the 22 miles and then – in exultation of spirit – retracing their steps as if the ascent were nothing.

In testimony to the Byzantine belief that the Ayalon Emmaus was the village in Luke, we find on the spot the remains of a large basilica from that period. The Crusaders built a church in its nave, but the remains of the two older side aisles are visible. Nearby is a Byzantine baptistery, and extending from it is the ruin of a structure that may have been a later Byzantine church, erected after the first was destroyed. All of these buildings were oriented southeast toward Jerusalem, rather than the usual east.

Just northwest of the churches is the mosaic floor of a 4th century villa. About 250 yards northeast of them are remains of a three-room bathhouse built around 221 AD during the city's reconstruction as Nicopolis.

In the 13th century, the Mamelukes transformed this bathhouse into a shrine commemorating Abu Ubaida. Six hundred years earlier, the Muslim general of this name had commanded the Arab armies that conquered the land from the Byzantines. Because of its position, Emmaus was at that time (637 AD) the largest Arab military and administrative base in the country. In 639, however, plague struck the city, killing most of its population and spreading throughout the land. "The plague of Emmaus" it was called. One of the victims was Abu Ubaida himself. As a city, Emmaus never recovered. Instead, a village grew here.

The Crusaders built a church in the nave of the Byzantine basilica, although they also built an Emmaus church at "Abu Ghosh," a name from the 19th century. Before that, this village preserved the name of Biblical Kiryat Yearim, where the Ark of the Covenant was kept1 Samuel 6:21 - 7:2 They [the men of Beth Shemesh, after receiving the ark back from the Philistines] sent messengers to the inhabitants of Kiriath Jearim, saying, “The Philistines have brought back the ark of Yahweh; come down, and bring it up to yourselves.” The men of Kiriath Jearim came, and fetched up the ark of Yahweh, and brought it into the house of Abinadab in the hill, and sanctified Eleazar his son to keep the ark of Yahweh. It happened, from the day that the ark stayed in Kiriath Jearim, that the time was long; for it was twenty years: and all the house of Israel lamented after Yahweh. for twenty years, until a dancing King David brought it into Jerusalem. The place is the proper distance (7 miles) from Jerusalem, and it had a caravenserai - but no early Emmaus tradition! After the Mamlukes expelled the Crusaders from the Judean hills in 1244, Christian pilgrims to Jerusalem no longer had access to the spot. They were obliged to travel by way of a village called al-Qubeiba, which also lay 7 miles from the Holy City. The Crusader tradition for Emmaus shifted, therefore, to al-Qubeiba, and here another Emmaus church was built. (There is no basis for the occasional claim that a "Castellum Emmaus" existed in al-Qubeiba since Roman times.) Let us return, therefore, to the site by the plain. The Crusaders may have been naïve as archaeologists and Biblical scholars, but they knew a strategic spot when they saw one. In 1133 they built a fortress, Castellum Arnaldi, to control the passage to the Beth Horon ridge. Between 1150 and 1170, the Templars added another fort a few hundred yards to the west. They named it Toron of the Knights. "Toron" was probably the source of the name "Latrun," which is applied to the area today. (Local guides in the 15th century, however, traced the name "Latrun" to the Latin for "thief," latro, claiming that the better of the thieves who died beside Jesus had his hometown here.) From these fortresses Richard the Lion Hearted vainly attempted to regain Jerusalem for the Crusaders in the summer of 1192.

The Mamlukes came next. As mentioned above, in the 13th century they set up the shrine to Abu Ubaida. Murphy-O'ConnorJerome Murphy-O'Connor, The Holy Land, Oxford Univ. Press, 1998 (pp. 321-22) suggests that they may have intended by this act to establish a religious claim to the strategic place, where Christians had interests.

An active Cistercian monastery, famous for its wines, today stands beside the ruins of Toron. Nearby the British built a fort in the Mandate Period, following the geographical logic that had guided the Greeks, the Romans, the early Muslims, the Crusaders and the Mamlukes. The same logic led to a famous battle at Latrun between the Israelis and the Arabs in the 1948 War. In the words of George Adam Smith (p. 153)George Adam Smith, The Historical Geography of the Holy Land, Jerusalem, Ariel, 1974 (30th edition) "History never repeats, without explaining itself."