Jericho

The combination of water, fertile ground and high heat makes it possible to grow tropical plants here. Today one sees papaya, mango, bananas and citrus, including pomelo. In the Roman period, the Jewish inhabitants grew spices and perfumes, including the balsam shrub, from which they manufactured a perfume of great aphrodisiac power whose secret, for better or worse, has been lost. The HasmoneansThe Hasmoneans: family of Judah Maccabee ("the hammer") and his brothers, who revolted successfully against the Greek Empire in 167 BC. They purified and re-dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem, establishing the festival of Hanukah ("dedication"). They ruled till 63 BC, and their domain extended almost as far as King David's. , followed by HerodHerod ruled the land under Roman auspices from 37 - 4 BC. After his death, the Romans called him "the Great" because of his building activities. Christians chiefly remember him, however, as the killer of the innocent children (Mt. 2: 16)., were eager to grow these plants, so they harnessed additional springs in the river beds to the west, leading the waters onto the plain. They thus turned the city into a garden which, JosephusJosephus Flavius (36 – 100 AD), Jewish general, one of two directing the revolt against Rome in Galilee. After Vespasian captured him, he prophesied the latter would be emperor. When this proved true, the Romans honored him. He then turned historian, writing The Jewish War, The Antiquities of the Jews and many other books. Because of a paragraph about John the Baptist (and maybe a sentence about Jesus), the Church preserved his works. tells us, was eight miles long and more than one wide. Jericho must have been an aromatic place: its Arabic name, ariha, means "scent."

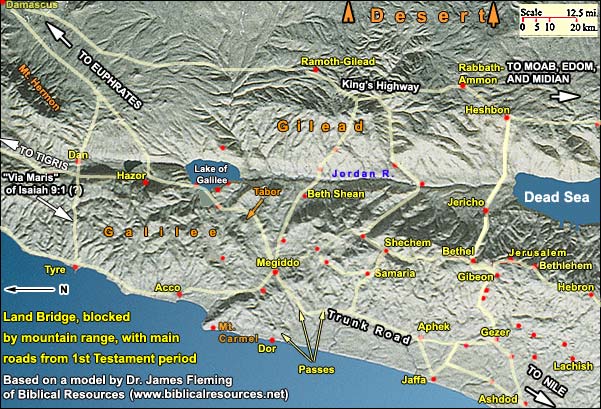

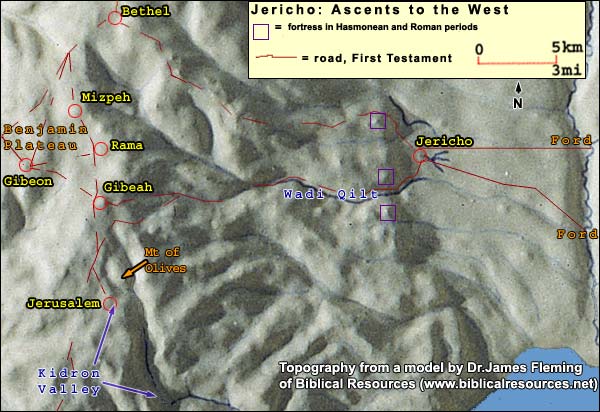

In addition to its natural graces, the city also had a good commercial position on the southernmost of the three major link roadsThere were three viable east-west link roads between the international highways. The northernmost went through the valley of Beth Shean, the middle one through the pass at Shechem, and the southernmost across the Benjamin Plateau just north of Jerusalem. South of the latter, the east-west crossing was difficult and hazardous. between the international trunks. Of all the links, this Gezer-Jericho road permitted the quickest access to the King's Highway at Heshbon 20 miles east. The city also sat on a north-south route stretching down the Jordan Valley. And once Jerusalem was established as a capital, anyone coming from the east would likely approach it through Jericho - as Jesus did (Luke 19:1He entered and was passing through Jericho.).

{mospagebreak title=The Oldest City}

The Oldest City Yet Discovered

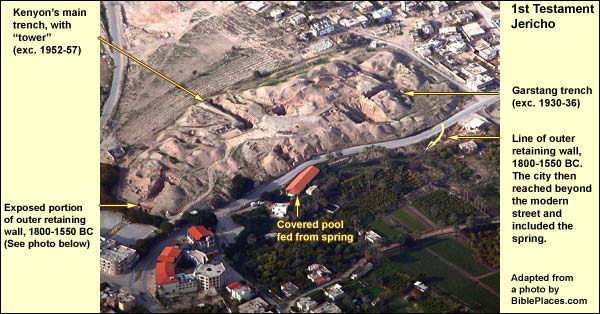

Today we climb seventy feet to the top of Jericho's tellIn general, before the Roman period, a city needed a hill for defense, with a spring nearby. Certain proportions had to be right: the hill had to be small enough so that the population supplied by the spring would suffice to produce enough soldiers to defend a wall surrounding the hill. You needed enough good agricultural land to feed that population. (You also needed peasants in nearby villages to work the land – about ten for every aristocrat in the city.) If you wanted to engage in commerce, you had to be near a decent road. Only certain hills fulfilled these requirements, and therefore people kept building on them. That is why we find layer after layer on some few hills, called tells, while others remained unsettled., but unlike other ancient cities in the land, Jericho was not founded on a hill. The whole mound consists of cities. Dame Kathleen Kenyon, digging here from 1952 through 1958, expected indeed to find a natural hill. Yet the deeper she went, the more cities she found. By the time she reached the level of the plain, she was back in what is known as the NeolithicThe Neolithic or "New Stone" Age, 8000 – 4500 BC. Human beings began to cultivate wheat and barley, at first in the steppes of Asia Minor (Turkey today). From about 5000 BC, they were making pottery. period. Since this preceded the invention of pottery (5000 BC), she had to use carbon dating. Testing samples of burnt grain from houses built against a stone tower, she put the age of the city at more than 9000 years (3000 older than any other known city).

The choice of this site for a city must have been influenced by the excellent spring (4.4 cubic metersOne cubic meter = 1000 liters. One liter = 1.056 liquid quarts. per minute). At one time purified by the prophet Elisha (2 Kings 2:19-22,The men of the city said to Elisha, “Behold, please, the situation of this city is pleasant, as my lord sees; but the water is bad, and the land miscarries.” He said, “Bring me a new jar, and put salt in it.” They brought it to him. He went out to the spring of the waters, and threw salt into it, and said, “Thus says Yahweh, ‘I have healed these waters. There shall not be from there any more death or miscarrying.’” So the waters were healed to this day, according to the word of Elisha which he spoke.) it is to be seen just east of the tell.

The tower had been adjacent to mud-brick houses, 12 - 18 feet in diameter, on the pattern of round tents. The floors were bedded with stone, topped by clay plaster. The residents kept groups of jawless skulls beside them in the house, burying the headless bodies under the floor. Perhaps this was a form of ancestor worship: once there is a house to bequeath, the beneficiaries venerate those who bequeathed it.

After ascending the tell, we can look down on the Neolithic tower. Its function isn't clear: a defensive tower would project beyond the city wall, but this did not. Below we can see its entrance. On the inside, twenty steps lead to the top, which shows no trace of a defensive barrier. Since the town was so low, this may have been a watchtower -- not just to warn against an enemy, but to guard the crops against thieves or animals.

On the tower's west side, Kenyon discovered a succession of massive protective walls, rebuilt several times. They may have circled the town for defense, or their function may have been to ward off silt from a wadi on the west.

The tower has not been reconstructed. Although modest compared with the pyramids, it pre-dates them by as much time as separates us from them: 4500 years. It is the oldest public structure known. Its existence implies a number of things. First, people had the means and leisure to build such a thing. It was the age of horticulture (farming with a flint hoe). The largest hunting and gathering societies, in the best environments, never number more than a few hundred people (LenskiLenski, Gerhard E. Power and Privilege. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1984., p. 98), but this city covered ten acres, room for a thousand or more. Nor would hunters have had the leisure to build this structure, which required the import of 1600 cubic meters of stone. It reflects "the existence of social organization and central authority which could recruit, for the first time in human history, the necessary means and manpower for such building operations." (Mazar,Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000 - 586 B.C.E., New York: Doubleday, 1990 p. 42.)

Underneath the level of the tower, Kenyon found a sequence of packed floors, on which hunters and gatherers had erected straw huts. Beneath them was the very first structure here: a mud platform with depressions around it (meant perhaps to hold cultic offerings), which she dated to 10,000 years ago. She also turned up a series of tools from the earliest level up through the time of the Neolithic town (on display at the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem). Studying them, one can trace the transition to agriculture: from the kind of flint that is suited for cutting grain stalks one by one (wild grain) to a sickle-type suited for cutting several together (cultivated). (When and where did people start farming?Agriculture did not begin in the luxuriant valleys of Egypt and Mesopotamia, where there would have been "too much competition from the natural vegetation. It originated in the wooded rocky hills where competition was less intense and where the ancestors of modern crops were already growing in the open spaces between the trees." (See F. Nigel Hepper, Illustrated Encyclopedia of Bible Plants, Leicester, England: Inter Varsity Press, 1992, p. 76.) The first evidence of farming appears, as far as we know, ca. 8000 BC at a place called Catal Hüyük, high up on what is today the Turkish plateau.)

In the first period ("A") of Neolithic Jericho, there were three major phases of cities, each maintaining the same urban culture for roughly a thousand years. According to the Italian expedition now digging at the site, a mud brick house cannot be relied on after twenty years: one must build a new one. The mud of dismantled houses became the ground on which the next group built, until the level rose 25 feet and buried the tower.

At the level of 6000 BC, a change appears. The houses become rectangular. People continue to keep skulls in their living rooms, but they fill out the features of some with clay, putting sea shells in for eyes and restoring the color with paint.

In one of the houses of this period ("Neolithic B"), there was a niche in a wall, with a flat stone at the bottom. Nearby Kenyon found a carefully hewn basalt pillar 17 inches high. With the flat stone as a base, it fit the niche precisely. Here then is a very early example of the matzeva, or standing stone .

From about 5000 BC (when pottery was invented), the settlement at Jericho dwindled to insignificance, reviving around 3200. The new culture was different, with distinctive pottery. People buried their dead in the slopes outside the city. Kenyon located their city wall, which was rebuilt at least seventeen times till destruction came around 2350 BC.

Logistics for a visit to the tell:

Opening hours:

April 1 through September 30, from 8.00 - 17.00. (Entrance until 16.00)

October 1 through March 31, from 8.00 - 16.00. (Entrance until 15.00)

{mospagebreak title=Joshua's Jericho? }

Joshua's Jericho?

A new culture springs up abruptly at Jericho in the first part of the second millennium BC. The many finds from Jericho's graves show an Egyptian connection.

Since we are deep in the Dead Sea Transform,This rip in the earth's crust belongs to the divergence of the Asian and African tectonic plates. The Transform extends about 600 miles from the southern edge of Turkey to the Red Sea, reaching its deepest point – indeed, the deepest point on the face of the earth – at the Dead Sea (about 414 meters below world sea level). the area is subject to earthquake. At some stage, around the 17th century BC, a gas arose and destroyed decay-causing bacteria in one of the family graves. Some organic materials survived, including wooden furniture and boxes. (The contents of the grave have been moved to the Rockefeller Museum, where they are displayed as found.) The style seems very similar to that of Egypt, though simpler.

It was a time when people from this part of the Levant were settling in the Nile delta. They eventually took it over -- and were dubbed by the Egyptians "Hyksos,"Hyksos: In the 18th and 17th centuries BC, Canaanites settled massively in the eastern Nile delta, eventually seizing dominion over lower Egypt. The Egyptians called them "Hyksos" ("foreign rulers") – and managed to throw them out after a century. The ceramic remains, scarabs and weapons at the Hyksos capital of Avaris (biblical Zoan) are very similar to those found in contemporary Canaanite sites. In the century before this Canaanite conquest of lower Egypt, the major cities in Canaan received massive systems of fortification, including huge earthen ramparts, which gave many of the tells the shape they hold to the present day. foreign rulers. Hundreds of "Hyksos scarabsThere is a family of beetles called the Scarabaeidae, which includes June bugs and dung beetles. The ancient Egyptians regarded the latter as sacred, because of their behavior: they roll little dung balls, and this brought to mind a divinity rolling the sun each day across the sky. They sculpted them in stone and ceramic, using the result as a talisman or a seal, as on a ring. The base often contains hieroglyphics or images of gods, humans, animals and plants. Scarabs served both the living and the dead; when they are found, it is often in graves." were also found in the Jericho graves.

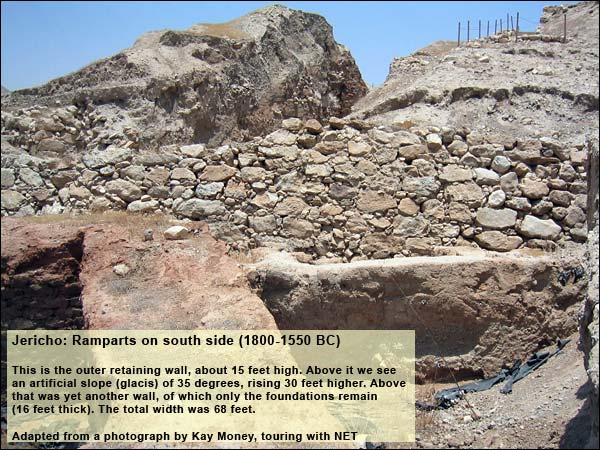

The city of this time included between ten and twelve acres, though a large part consisted of ramparts. Its wall extended eastward (beyond the modern road) to include the spring. (A section of the tell was removed to construct the reservoir and the road.) Because of the new technology of war (horses and chariots), this wall was also more massive than earlier ones. Thanks to a recent excavation, we can view it today on the south side of the tell, as well as the north. Its outermost section is a retaining wall of large stones rising about fifteen feet. Then comes a glacisAn artificial slope, steep enough to keep attackers from reaching a city wall on top., sloping up at 35 degrees, to a line about 30 feet above the top of the outer wall. Upon this bulwark stood yet another wall, 16 feet thick and of undetermined height (for only the stone foundations remain). The whole complex was 68 feet thick. It must have made an impression.

According to Kenyon, this city was destroyed (along with many others in the country) when the Egyptians established control in Canaan after driving out the Hyksos -- an event usually dated to 1550 BC, long before the time of Joshua. She finds no city at Jericho again until the 11th century, well after the time of Joshua.

In the early eighties, a few years after Kenyon's death, her detailed reports were published. Bryant G. Wood took a new look at her findings and re-evaluated them in the Biblical Archaeology Review (March-April 1990). The city with the impressive ramparts, he holds, endured all through the Middle Bronze Age (2100-1550 BC) and was destroyed in a period called Late Bronze IIA: about 1400 BC.

Wood's revision caused a stir, because it appeared to bring the city of massive walls two centuries closer to Joshua and the Israelites -- indeed, to the date that a chronology based purely on the Bible would suggest. Yet most archaeologists do not accept Wood's re-dating. Apart from that, they discern no trace of Israel in the land as early as 1400 BC. To this debate we now turn.

{mospagebreak title=Archaeological Debate}

When Did What Walls Fall?

The Archaeological Debate Over Jericho

In the first half of the second millennium BC, Jericho encompassed ten or twelve acres, though much consisted of ramparts. According to Kathleen Kenyon, this city was destroyed (along with many others in the country) when the Egyptians established control in Canaan after driving out the Hyksos - an event usually dated to 1550 BC, long before the time of Joshua. She finds no city at Jericho again until the 11th century, well after the time of Joshua.

In the early 1980's, a few years after Kenyon's death, her detailed reports were published. Bryant G. Wood took a new look at her findings and re-evaluated them in the Biblical Archaeology Review (March-April 1990). The city with the impressive ramparts, he holds, endured all through the Middle Bronze Age (2100-1550 BC) and was destroyed in a period called Late Bronze IIA: about 1400 BC. This would fit the date of Israel's entry into Canaan, if that date is reckoned by adding up the years in the Bible since Creation.

n the 1980's, Israeli archaeologists carried out surface surveys in the hill country between the Jezreel Valley and Beersheba. They found 248 sites in the Middle Bronze Age (2100-1550 BC), then a sudden drop to a mere 29 in the Late Bronze (1550-1200 BC) followed by an upsurge to 254 in Iron Age I (1200-1000 BC). (The upsurge reflects a great upheaval that took place throughout the Eastern Mediterranean in the late 13th and early 12th centuries BC.) These Iron-Age settlements were mostly small. They "possessed an overall material culture that led directly on into the true, full-blown Iron Age culture of the Israelite Monarchy" (DeverDever, W.G. "Cultural Continuity, Ethnicity in the Archaeological Record, and the Question of Israelite Origins." Eretz Israel, 24). Using the pottery and architectural styles of the Late Bronze period, it is impossible to distinguish the Israelites from other ethnic groups. One thing, however, does seem to work: the study of animal bones. At Ashkelon, Ekron and Timna (Timna in the Shephelah), three Philistine sites, between 8% and 18% of the animal bones belonged to pigs. These were popular at other lowlands sites as well. At Heshbon in the highlands of Transjordan, 5% of the bones belonged to pigs. At Ebal and Raddana, two Israelite sites, the percentage of pig bones was zero, and at Shilo, 0.1 (someone noshing on the sly). "(Pigs) disappear from the faunal assemblages of the hill country... The faunal assemblages of Iron II [1000-586 BC -- SL] reflect the same traits." (FinkelsteinFinkelstein, Israel. "Ethnicity and Origin of the Iron I Settlers in the Highlands of Canaan: Can the Real Israel Stand Up?", Biblical Archaeologist 59:4 (1996)., p. 206.) citing B. HesseHesse, B. "Pig Lovers and Pig Haters: Patterns of Palestinian Port Production." Journal of Ethnobiology 10: 195-225., pp. 217-218.

For the Cisjordanian highlands, William Dever"Save Us from Postmodern Malarkey," Biblical Archaeology Review 26:02, March/April 2000. writes:

Population estimates, based on site size and well-developed ethnographic parallels, indicate a central hill-country population of only about 12,000 at the end of the Late Bronze Age (13th century B.C.E.), which then grew rapidly to about 55,000 by the 12th century B.C.E. and then to about 75,000 by the 11th century B.C.E. Such a dramatic population explosion simply cannot be accounted for by natural increase alone, much less by positing small groups of pastoral nomads settling down. Large numbers of people must have migrated here from somewhere else, strongly motivated to colonize an underpopulated fringe area of urban Canaan, now in decline at the end of the Late Bronze Age. Here is the view of A. F. Rainey:"Israel in Merneptah's Inscription and Reliefs," Israel Exploration Journal, 51: 68 (2001) The Egyptian records reveal that the Shasu pastoralists were becoming more numerous and troublesome during the thirteenth century BCE. The archaeological surveys in the central hill country indicate that the Iron I settlements initially sprang up in marginal areas where pastoralists could graze their flocks and engage in dry farming. Later they spread westward, cleared the forests and began building agricultural terraces. Nowadays there is no compelling reason to doubt the general trend of the Biblical tradition that those pastoralists were mainly immigrants from Transjordan. Yet some of these new settlers may have come from within Canaan itself. In the 13th century BC, the Egyptians strengthened their hold on the lowlands. They took power from local notables and put it in the hands of Egyptian officials, imposing new laws on everyone. To escape the central authority, some probably shrank back into the hill country where they could be free.Conclusion: the Israelites first settled in the central highlands toward the end of the 13th century BC. This fits the first mention of Israel in an extra-Biblical document, namely the stele of Pharaoh Merneptah, which is dated to ca. 1205 BC.

Wood is aware of these arguments, but he holds to his position. One who agrees with it, David Livingston, proposes that the Israelites arrived around 1400 BC but that they lived for 200 years in tents, which leave no traces, until at last they decided to build houses. Yet why would they not build houses soon after arrival? They had no venerable tradition of living in tents. There was plenty of building material. Anyone who has braved the winter in the highlands of Cisjordan would use that material as quickly as possible.

Thus, even if Middle Bronze Jericho lasted till 1400 BC, as Wood maintains, we would still have a problem of two centuries. To eliminate them would require a major revision of archaeological analysis at several sitesEspecially at sites which, on the current reckoning, underwent destruction both in 1550 BC and again in 1300 BC, namely Aphek, Gezer, Timna (Tell Batash) and Tell Beit Mirsim.. The motive for such a revision would have to be a new chronology. Future work in radiocarbon dating and the counting of tree rings may supply such a motive, but so far it has not. In addition to the results from the Cisjordanian highlands, we have evidence from Egypt, again pointing to the end of the 13th century BC. For this, see our page on the exodus, entitled From Egypt to Canaan. Contrast, however, this article by Wood, which suggests the HyksosHyksos: In the 18th and 17th centuries BC, Canaanites settled massively in the eastern Nile delta, eventually seizing dominion over lower Egypt. The Egyptians called them "Hyksos" ("foreign rulers") – and managed to throw them out after a century. The ceramic remains, scarabs and weapons at the Hyksos capital of Avaris (biblical Zoan) are very similar to those found in contemporary Canaanite sites. In the century before this Canaanite conquest of lower Egypt, the major cities in Canaan received massive systems of fortification, including huge earthen ramparts, which gave many of the tells the shape they hold to the present day. period as the time of slavery in Egypt. When was the last Bronze-Age destruction of Jericho? If we leave the question of the Biblical story aside, we still have Wood's points dating a destruction of Jericho to 1400 BC. Do these points hold water? Should we revise the dating of Kenyon? 1. Imported Cypriot and Mycenean pottery constitute a clear and firm ceramic indicator for the existence of a city in the Late Bronze Age.(See MazarMazar, Amihai. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000 - 586 B.C.E.. New York: Doubleday, 1990., pp. 218, 261- 264.) Kenyon asserted that there was no city here in the Late Bronze period (1550-1200 BC) because she found no Cypriot ware. According to Wood, however, her predecessor, Garstang, did find Cypriot ware, though he did not recognize it as such. 2. Wood points out that in a cemetery just northwest of the tell, Garstang found scarabsThere is a family of beetles called the Scarabaeidae, which includes June bugs and dung beetles. The ancient Egyptians regarded the latter as sacred, because of their behavior: they roll little dung balls, and this brought to mind a divinity rolling the sun each day across the sky. They sculpted them in stone and ceramic, using the result as a talisman or a seal, as on a ring. The base often contains hieroglyphics or images of gods, humans, animals and plants. Scarabs served both the living and the dead; when they are found, it is often in graves. with the names of pharaohs from the Late Bronze period. But since such items were passed through the generations as heirlooms, they could have been laid in the grave in the Iron Age. Also, during times of pastoral nomadism, people sometimes buried their dead near tells that were not in use. (MazarMazar, Amihai. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000 - 586 B.C.E.. New York: Doubleday, 1990., p. 279.)3. In his article from 1990, Wood mentioned some charcoal that had been dated by the Carbon-14 method to around 1400 BC, but this dating was later corrected. All Carbon-14 dates from the last Bronze-Age destruction support Kenyon's dating. Since the amount of C-14 in the atmosphere varies at different times, raw C-14 dates are calibrated to actual dates by checking the C-14 in trees, whose rings can serve as an independent indicator. Wood cites studies showing regional differences among trees with respect to the quantity of C-14 at given times. Since there is not enough data from local trees to calibrate raw C-14 dates, Wood refuses to accept the above findings for Jericho. (For more, see dating.) Wood has made further arguments: 4. If Jericho was destroyed in 1550 BC, who would have done the deed? This was the time when the Egyptians drove the Hyksos out. It does not make sense that the fleeing Hyksos would have destroyed the town. As for the Egyptians, their records show them pursuing the Hyksos only as far as Sharuhen, a city in the Negev.

However, since Kenyon's dig at Jericho, archaeologists have found evidence of numerous destructions throughout the country, all dated to around 1550 BC. (To name just some of the better-known cities that fell: Hebron, Shiloh, Jerusalem, Gezer, Aphek -- in addition to Sharuhen.) The destroyers may have been local people, taking advantage of the collapse of Hyksos control. Or they may have been, pace Wood, the Egyptians, who established control over Canaan during the next hundred years. (See Mazar,Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000 - 586 B.C.E., New York: Doubleday, 1990. pp. 226-27.)

In this connection, one discovery is puzzling. In the destruction layer of the last Bronze Age Jericho, Kenyon found storage jars containing six bushels of grain. Wood dwells on this point. The find speaks against a long siege, for the grain would have been eaten. It also speaks against a conquest by the Egyptians, who preferred to attack before the harvest, taking the crops for their troops and laying siege to the cities.The presence of grain suggests that the harvest was recently past, which could indicate springtime, as fits the Biblical account. Moreover, one would expect the conquerors to eat the grain - unless they were prohibited by God from taking anything, as the Israelites were. Puzzling as the find may be, however, we have already seen that the Israelites would not have been here either in 1550 or in 1400 BC - unless, of course, we accept the suggestion that they lived in tents for 200 years.

{mospagebreak title=Mount of Temptation }

The Mount of Temptation

After baptizing Jesus, John is arrested. Jesus, taking over from him, does not immediately go up to Galilee to start his public mission. Rather, he is led by the spirit into the desert, where the devil tempts him.

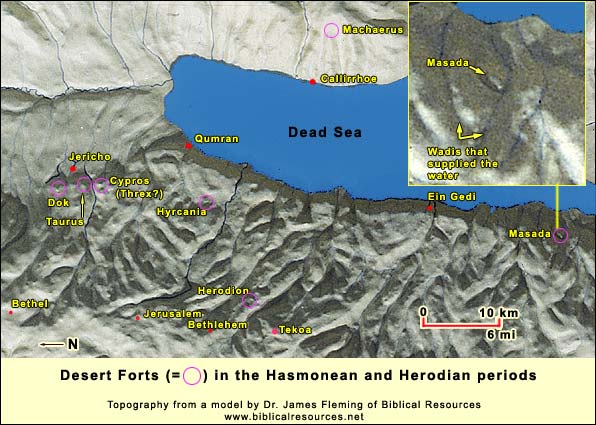

Standing on the tell of ancient Jericho and looking west, we see a cliff. A monastery is built into it. This is Qarantal ("the forty"), the Monastery of the Temptation. In its present form it dates to 1887. Byzantine monks first founded a monastery here, which they named "Dakun," after the earlier Hasmonean fortress here, called "Dok" (Aramaic for "viewing point"). In the chapel near the altar is a rounded piece of the bedrock, resembling a loaf of bread. It was this, perhaps, that attracted the tradition of Matthew 4:1-3.Then Jesus was led up by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil. When he had fasted forty days and forty nights, he was hungry afterward. The tempter came and said to him, “If you are the Son of God, command that these stones become bread.”

Six Greek Orthodox monks live in the monastery today. As the name implies, the view is grand. One might see "all the kingdoms of the world." Check the opening hours on the sign below before you climb. The monastery requires modest dressShoulders covered, legs covered below the knees..

Above Qarantal, on top of the cliff, is a wall. Because the first temptation was already located here, the place also attracted the third, in which "the Satan" (meaning, in Hebrew, the adversary) shows Jesus the kingdoms. The Greek Orthodox built this wall in the hope of founding a monastery here, but their money came largely from Russia, and in 1917 it dried up.

The wall, however, sits on the ruins of the HasmoneanThe Hasmoneans: family of Judah Maccabee ("the hammer") and his brothers, who revolted successfully against the Greek Empire in 167 BC. They purified and re-dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem, establishing the festival of Hanukah ("dedication"). They ruled till 63 BC, and their domain extended almost as far as King David's. (later Herodian) fortress, Dok. Its function was to guard the link roadThere were three viable east-west link roads between the international highways. The northernmost went through the valley of Beth Shean, the middle one through the pass at Shechem, and the southernmost across the Benjamin Plateau just north of Jerusalem. South of the latter, the east-west crossing was difficult and hazardous., for beneath it an unbroken ridge leads up toward the central plateau of the hill country. Dok was the scene of a gruesome event during the reign of the Hasmoneans, as reported in Josephus.

To the left of Qarantal, we see caves. Here archaeologists found the skeletons of 38 Jewish rebels, all sharing a genetic defect in the teeth (hence probably relatives) who had taken refuge in the caves at the end of the Bar Kokhba revolt. The Romans probably built a fire in the mouth of the cave and smoked them to death.

Above these caves are the antennas of Israel's army, performing the same guard duty as the ancient fortress. In the words of George Adam Smith, "History does not repeat itself without explaining itself, and the explanation is usually geographical."

{mospagebreak title=2nd Testament City }

Second Testament Jericho

According to JosephusJosephus Flavius (36 – 100 AD), Jewish general, one of two directing the revolt against Rome in Galilee. After Vespasian captured him, he prophesied the latter would be emperor. When this proved true, the Romans honored him. He then turned historian, writing The Jewish War, The Antiquities of the Jews and many other books. Because of a paragraph about John the Baptist (and maybe a sentence about Jesus), the Church preserved his works., the Jericho of his day was a garden city, eight miles long and more than one wide, irrigated by Elisha's spring. In fact, the HasmoneansThe Hasmoneans: family of Judah Maccabee ("the hammer") and his brothers, who revolted successfully against the Greek Empire in 167 BC. They purified and re-dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem, establishing the festival of Hanukah ("dedication"). They ruled till 63 BC, and their domain extended almost as far as King David's. and Herod Herod ruled the land under Roman auspices from 37 - 4 BC. After his death, the Romans called him "the Great" because of his building activities. Christians chiefly remember him, however, as the killer of the innocent children (Mt. 2: 16).brought water from many springs, because under the tropical conditions, they could grow the costliest spices and perfumes, especially balsam (Jewish War,Josephus Flavius, The Wars of the Jews, translated by William Whiston IV 8.3). For this reason Cleopatra of Egypt coveted Jericho, doing all she could to get it from Herod. Eventually she succeeded, and he had to lease it back from her until her suicide in 31 BC.

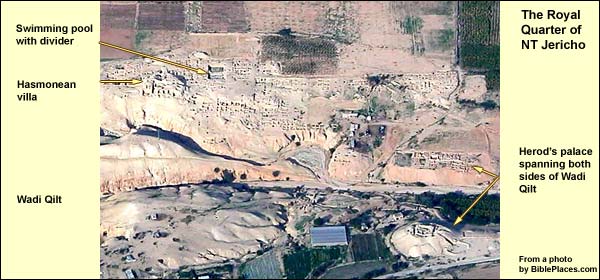

Heading south from Tell e-Sultan, we take a brief look at one of the three surviving fig sycamores in Jericho (Zacchaeus! Luke 19:1-8.He entered and was passing through Jericho.There was a man named Zacchaeus. He was a chief tax collector, and he was rich. He was trying to see who Jesus was, and couldn’t because of the crowd, because he was short. He ran on ahead, and climbed up into a sycamore tree to see him, for he was to pass that way. When Jesus came to the place, he looked up and saw him, and said to him, “Zacchaeus, hurry and come down, for today I must stay at your house.”He hurried, came down, and received him joyfully. When they saw it, they all murmured, saying, “He has gone in to lodge with a man who is a sinner.” Zacchaeus stood and said to the Lord, “Behold, Lord, half of my goods I give to the poor. If I have wrongfully exacted anything of anyone, I restore four times as much.”). We then continue south. Crossing a riverbed (Wadi Qilt), we make the next right. We are now following the line of the old Roman road toward Jerusalem, with the riverbed on our right. After a kilometer, we see a small mound before us and pull off to the right in front of it. This was part of Herod's winter palace. A bridge crossed the river to the main part of the palace on the other side, the outlines of which are clearly visible.

Here Herod died, at the age of 69, in 4 BC. Josephus tells the story

Today the water of Wadi Qilt is led to the fields before it reaches this point, but Herod had the river flowing through his palace.

Before Herod's time, this area was the royal quarter of the HasmoneansThe Hasmoneans: family of Judah Maccabee ("the hammer") and his brothers, who revolted successfully against the Greek Empire in 167 BC. They purified and re-dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem, establishing the festival of Hanukah ("dedication"). They ruled till 63 BC, and their domain extended almost as far as King David's.. North of the palace, near the foot of the cliff, is a small excavated hill. It was the palace-turned-villa of Alexandra, mother of Mariamne, whom Herod fiercely loved. Alexandra had a 17-year-old son named Aristobolus. She got Mariamne to pressure Herod to appoint him High Priest. As soon as he had done so, however, Herod rued the decision. For the youth soon proved very popular (he had the blood of the freedom-fighting Hasmoneans in his veins) and for the last hundred years the high priest had also been king. Herod, on the other hand, was a "mere" Edomite, whose paternal grandfather had converted to Judaism, and his fellow Jews considered him a collaborator with Rome.

Fearing a coup, Herod decided to cut his losses. When Alexandra invited him to Jericho after the Feast of Tabernacles, he ordered his courtiers to drown the boy, as if by accident, in the swimming pool. This is visible just east of the villa (one must visit by foot in order to see it). See Josephus (Antiquities,Josephus Flavius, Antiquities of the Jews, translated by William Whiston XV.3.3.

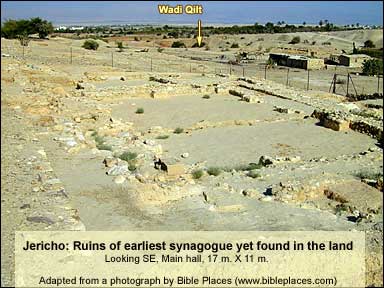

East of the pool, in 1998, archaeologist Ehud Netzer found remains of a colonnaded hall that may have served as a synagogue. If so, it is the earliest yet discovered; it was built in the time of the Hasmoneans, between 75 and 50 BC and destroyed in the earthquake of 31 BC.

{mospagebreak title=Jericho Road}

The Jericho Road

On leaving Jericho, Jesus healed the blind Bartimaeus (Mark 10:46-51).

Heading south from Tell es-Sultan, we cross a riverbed (Wadi Qilt) and make the next right. We are now following the line of the old Roman road toward Jerusalem, with the wadi on our right. After one kilometer we shall spot, across the river, Herod's winter palace. (See Second Testament Jericho.)

(Note: The ascent from here is hazardous, a two-way street. Drive with care -- and not at all when it's wet.)

When Jesus climbed this road toward Jerusalem in 30 CE, he did not see palaces. All had burned down in the brief revolt that followed Herod's death.

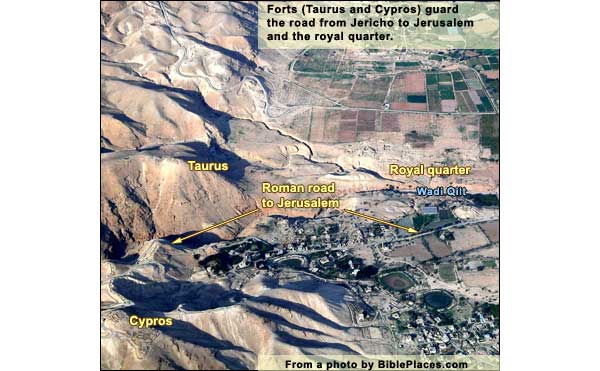

To our west yawns the canyon of Wadi Qilt, guarded by two fortresses. There is the cone of Cypros on the south bank. (Cypros was Herod's mother; this may have been the HasmoneanThe Hasmoneans: family of Judah Maccabee ("the hammer") and his brothers, who revolted successfully against the Greek Empire in 167 BC. They purified and re-dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem, establishing the festival of Hanukah ("dedication"). They ruled till 63 BC, and their domain extended almost as far as King David's. fortress, Threx.) On the north is the half-cone of Taurus. In the region east of Jerusalem, this wadi is the only natural opening in the cliff along the Jordan Valley.

In First Testament times, before there was an aqueduct along the bank of the wadi, people would take the upper, easier road (the one we are on) in winter and spring, drinking from the cisterns. In summer and autumn, they would stay in the canyon, drinking from the springs and resting in the shade. The Hasmoneans put in the first aqueduct from springs to the west. Then there was always water available on this upper road, and it became the only one.

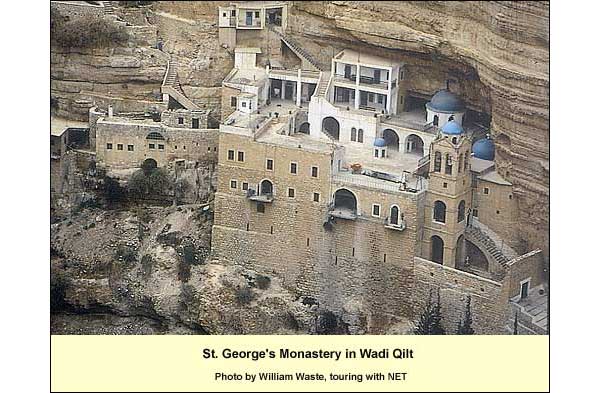

In the face of the north bank, as we drive, we can see the caves of Byzantine monks. We come to a large gate and continue about 200 yards. Here we stop and climb to a cross, from which we can see St. George's monastery, nestled in the northern cliff face. To its left and ours, a functioning aqueduct (1945) crosses the wadi, bringing water to the fields around Jericho.

St. George's shares a number of traits with Qarantal. It is Greek Orthodox. It too contains just a few monks today. In its present form it dates from the nineteenth century, but with traces of Crusader and Byzantine predecessors. Although founded by Syrian monks in the fifth century AD, the monastery takes its name from a great teacher, George of Kosiba, who lived and taught here in the sixth and seventh centuries, dying seven years after the Persian conquest of 614.

This is a good place to consider the road on which we are driving. We can measure the 13 miles from Jerusalem to Jericho, because to the west we can see a tower on Mt. Scopus overlooking the city beyond, while on the right we can see the wall of Dok. Surrounded by desert, this was a dangerous road. Outlaws could get control of the watering places. An army might come to try and bring order (think of Saul chasing David) but it could not long endure on limited water supplies. (The exception was Masada). Once the army went back to the city, the outlaws returned to their posts. (In the nineteenth century, pilgrims had to travel in groups from Jerusalem to the Jordan, paying protection money to the Beduin.) It is not a coincidence, then, that Jesus sets the Parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10: 25-37) on this road.