Via Dolorosa

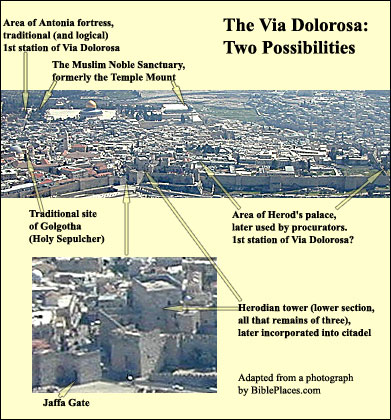

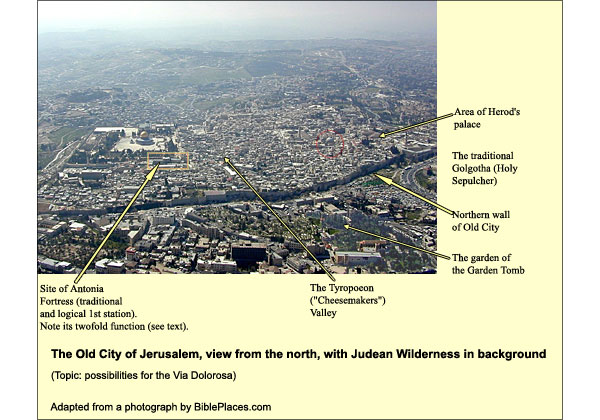

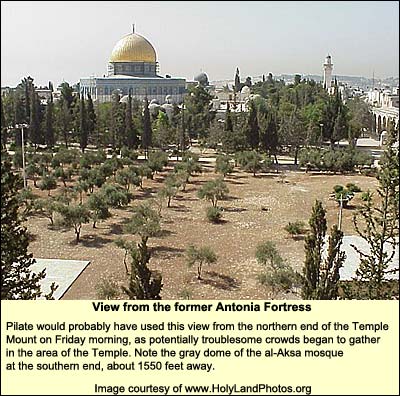

Some scholars favor the notion that Pilate interrogated Jesus on the west side of the Old City, near the Citadel south of today's Jaffa Gate. Southward from this Citadel spread Herod's palace, about 900 feet long. Here Pilate would have resided on coming up from Caesarea to oversee events during Jewish festivals (Philo, Delegation to Gaius, 38). John 19:13 places the encounter at Gabbatha, which means "high point," and this palace occupied the highest point in the city. Finally, the Gospels tell us that the trial took place "on the judgment seat" (Matthew 27:19). JosephusJosephus Flavius (36 – 100 AD), Jewish general, one of two directing the revolt against Rome in Galilee. After Vespasian captured him, he prophesied the latter would be emperor. When this proved true, the Romans honored him. He then turned historian, writing The Jewish War, The Antiquities of the Jews and many other books. Because of a paragraph about John the Baptist (and maybe a sentence about Jesus), the Church preserved his works. describes a hearing before the palace on such a seat in 66 AD; it too resulted in crucifixions: Now at this time Florus took up his quarters at the palace; and on the next day he had his tribunal set before it, and sat upon it, when the high priests, and the men of power, and those of the greatest eminence in the city, came all before that tribunal. (WarWar= Josephus Flavius. The Jewish War. Translated by William Whiston. (Abbreviated in text as War.) II 14.8) More from Josephus' account... Yet this tribunal sounds improvised. There is a good argument for locating the event in the Antonia Fortress. Part of its expanse is occupied today by the Omariyya School, site of the official "First Station." Pilate had come to Jerusalem to supervise events lest they get out of hand. His best observation point would have been the Antonia, for the Temple courts, where people gathered, lay below. The Antonia had been built by Herod with a double purpose: to guard against attacks from the north (where alone there was no protecting valley), but also as a fort from which the ruler might keep watch over the Temple.

(Pilate had good reason to be nervous. According to Smallwood (in the Penguin Jewish WarThe Jewish War. Translated by G.A. Williamson. Penguin, 1981., p. 465), he couldn't have had a legion under him. The legate of a legion had to be of senatorial rank and could not serve under Pilate, a mere equestrian. Pilate's army consisted of 3000 soldiers, mostly local Gentiles -- not enough to rule Judaea. With no inkling of the Jewish covenant faith, the Romans had vastly underestimated the chances of unrest. A few years before, Pilate himself had learned otherwise. Philo reports that he was quick to crucify without judicial process.)

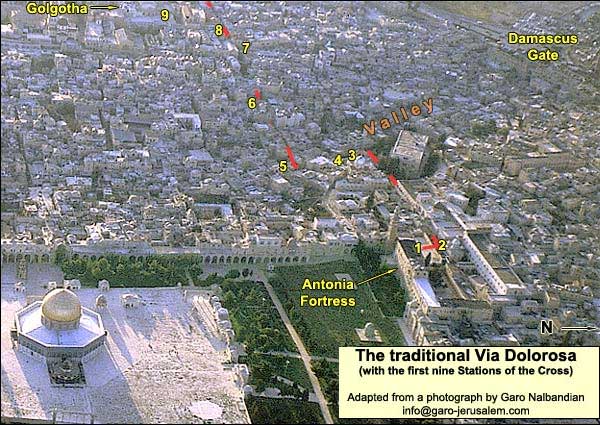

Apart from the Antonia, we have no other site that we can logically or historically connect to the Via Dolorosa. At one time it was believed that the ancient stone pavement or lithostrotos in the Convent of the Sisters of Zion had belonged to it. Likewise, the high arch we see on the street, just west of this pavement, was called Ecce Homo: pilgrims thought that Pilate had here presented Jesus to the people, saying "Behold, the Man!" (John 19:5). Since the late 1970's, however, archaeologists have established that Hadrian built both the pavement and the arch, probably after putting down the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135 AD. The pavement was part of his eastern forum (whose counterpart on the west was at the present Muristan, southeast of the Holy Sepulcher). Instead of walls, Hadrian built a series of monumental arches, one of which was later mistakenly dubbed the "Ecce Homo." As for the endpoint of the Via Dolorosa, the empty Sepulcher, was it the place? There are several arguments in its favor, we shall see, though none are decisive. {mospagebreak title=Stations of the Cross} The Stations of the Cross No matter where the historical route may have run, the fact remains that Jesus did walk through this city on his way to death. We can walk the Via Dolorosa while attempting to concentrate mind and spirit on that fact. One can join the Franciscan procession, which begins at the first Station of the Cross, the Omariyya School, on Friday at 15:00. (To double check on the time, call 02 - 627 2692.) The procession forms a world apart from the bustle of the markets, stopping and praying at each station. Peddlers and shopkeepers do not disturb it. (Or one can form one's own procession.) As the Franciscans visit the stations, they are as follows. 1. The Condemnation. The event is remembered in the courtyard of the Omariyya school, accessible only after 13:00 on school days. At that time it is usually quiet enough that one may read from the Gospel, e.g., Mark 15: 1-20. The place offers a good view of the Dome of the Rock, such as Pilate would have had from here when supervising the Temple and its courts.

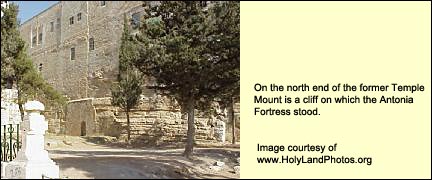

On this site stood part of the Antonia fortress. The cliff, 45 feet high above the Haram, may originally have extended southward -- and the fortress too. Standing below, one can see the cliff on which the Antonia stood. 2. Imposition of the Cross. We can remain out on the trafficked street or enter the Franciscan courtyard. Inside on the right is the Chapel of the Flagellation, renovated in 1929 on the basis of a medieval church, the first on the spot. To the left is the Church of the Condemnation of Christ and the Imposition of the Cross (1904). Inside one can see Hadrian's paving stones, which continue in the convent to the west. Some of the stones have grooves cut in them to keep people and animals from slipping. This grooved part must have been a street in 135 AD. The courtyard also contains a Franciscan museum. This includes the 175 fragments of graffiti found at the "House of Peter" in Capernaum. If the First Station is inaccessible, we can do the reading in this courtyard.

3. Jesus Falls for the First Time. (Not in the Gospels.) We descend the hill to the Cheesemakers' Valley. Turning left, we step on some ancient paving stones, discovered while renovating the sewage system a few decades ago. On the east side of the street, above, a relief shows Jesus falling under the weight of the cross. If the gate is open, we may enter the courtyard of the Armenian Catholic chapel to find some peace and read. 4. Jesus Meets His Mother. (Not in the Gospels.) On the street, this station is visible just south of the third. But if we can find the attendant in the courtyard of the Armenian chapel (see above), we can gain admission from there to the Armenian Church of our Lady of the Spasm. It contains a simple, powerful mosaic.

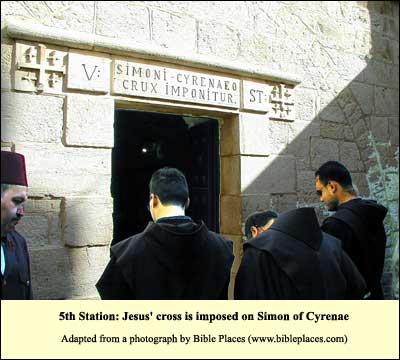

5. Simon of Cyrene. "They pressed into service a passer-by coming from the country, Simon of Cyrene (the father of Alexander and Rufus), to bear His cross." (Mark 15:21.) (Since Simon's sons are named without further identification, they were probably people familiar to the congregation that Mark was addressing.) A short distance from where we turned into the Cheesemakers' Valley, there is an alley on the right leading up the western hill. This station is marked at its corner. The location fits the account: Jesus, exhausted from abuse, now faces this formidable ascent. The Romans judge it will be too much for him and impose the cross on Simon. 6. VeronicaAfter putting down the first Jewish revolt, Titus carried on a torrid love affair with the beautiful Hasmonean princess, Berenike (Bernice), at Banias (Caesarea Philippi). He wanted to make her Empress, but the people of Rome wouldn't stand for it, so he sent her back to her country to wait -- and never called.Eusebius of Caesarea Maritima, in the fourth century, recorded seeing at Banias a piece of bronze statuary in which a woman bending on one knee extended her hand as a suppliant to a standing man whose hand reached toward her. This may have been a local memory of the Titus-Berenike affair. Or it could have been related to Hadrian's coins, which showed the Emperor in a similar gesture, restoring rights to his provinces. The Christian citizens of Caesarea Philippi (Banias), however, interpreted the pair of statues as representing Jesus healing the woman with an issue of blood. By the fourth century they were calling her Berenike!According to another legend, current by 400, Jesus sent his portrait to a princess of Edessa named Berenike. The two or three Berenikes were then identified. B became V and we got Veronica. In medieval legend, she acquired her picture of Jesus not from correspondence with him, but rather from the cloth she used to wipe his face on the Via Dolorosa.. (Not in the Gospels.) About 40 yards up the hill, the side of a small pillar protrudes from the wall on the left, containing the name Veronica. Legend has it that one of the women lining the road reached out with a cloth and wiped the blood and sweat from the face of Jesus. His image appeared on the cloth. The name of the woman may be derived from this event: vera icona, true image.

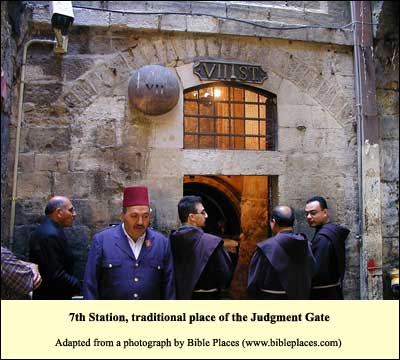

7. Jesus Falls a Second Time. (Not in the Gospels.) At the top of the hill, this station may mark the western limit of the city on that day in 29 or 30 AD. Tradition places a gate here, with a copy of the death sentence posted on it. Christians later called it the Judgment Gate. Jesus is thought to have fallen here a second time. A little more than a century later, one of the two main north-south streets of Jerusalem (then Hadrian's Aelia Capitolina) ran here. It was called the Cardo MaximusThe Cardo was the main north-south street in Roman urban planning, the "hinge" on which the life of the city revolved. . The current alley, known as Suk Khan e-Zeit, occupies only a sliver of this, for the Cardo was a broad pillared street. Its southern extension, Byzantine periodThe Byzantine period – that is, the period of the Eastern Christian Roman Empire –may be dated from 330 AD, when Constantine re-named the city of Byzantium "Constantinople" and dedicated it to the God of the Christians. Its end, in this land, came in 638, when the Muslims took Jerusalem. Elsewhere it lasted much longer: Constantinople finally fell to the Turks in 1453., is exposed in the Jewish Quarter. 8. The Women Weep. Just to the left (south) of Station VII, there is a lane going uphill. Taking it, we leave the city of that time. A few steps up, on the left, is a small stone in the wall, with a cross and an inscription including the letters NIKA, referring to the victory of Jesus Christ. Here tradition places Luke 23: 27-31 And following Him was a large crowd of the people, and of women who were mourning and lamenting Him. But Jesus turning to them said, "Daughters of Jerusalem, stop weeping for Me, but weep for yourselves and for your children. For behold, the days are coming when they will say, 'Blessed are the barren, and the wombs that never bore, and the breasts that never nursed.' Then they will begin to say to the mountains, 'Fall on us,' and to the hills, 'Cover us.' For if they do these things when the tree is green, what will happen when it is dry?" 9. Jesus Falls for the Third Time. (Not in the Gospels) A Greek convent blocks the approach to this station, so we have to retrace our steps to the street of Station VII, Suk Khan e-Zeit (on the line of the ancient Cardo), and head south. After a trek through the market, which serves the local people, we arrive at a staircase on the right, next to Zalatimo's Sweets. In the terms of 135 AD, we are standing before the entrance of Hadrian's Temple to Venus (or possibly Jupiter), built not quite perpendicular to his Cardo. In the terms of 336 AD, we are standing before the triple gate of Constantine's Church of the Resurrection. We ascend the steps and head west, but before the gate of an Ethiopian monastery, we turn north and then west again. In front of us is the gate of the Coptic Patriarchate. In the left corner, tilted, a pillar marks the Ninth Station, where Jesus is thought to have fallen a third time.

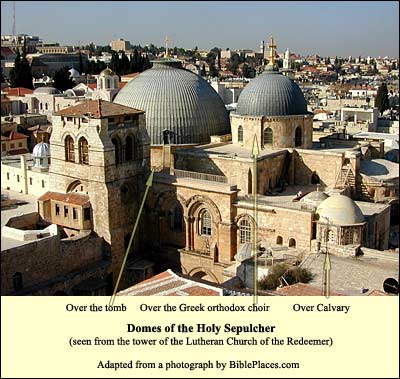

Walking through a gate beside the pillar, we find ourselves on a roof with a dome. The latter was built by the Crusaders. Its windows let light into a large crypt below, called the Chapel of St. Helena, near the pit where the knights thought Constantine's mother had found the true cross. If we were here in the Crusader period, we would see church walls to the north, east and south (there is a remnant, still, on the south). They belonged to the convent of the Latin clergy, who officiated in the church. Ethiopian monks live here today, although the Copts claim the place. To the southwest, on the roof, is a small white dome. Beneath it is an outcropping of bedrock, which tradition identifies as Calvary. This roof is usually a quiet place. We can sit and read the Gospel account through the burial. The remaining Stations of the Cross are inside the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. We can reach it in two ways. (1) We can head through a small door SW of the dome. This leads through the Chapel of the Ethiopians, then down a staircase to the Coptic Chapel of St. Michael, and out into the courtyard. Or (2) we may head back the way we came, to the lively Khan e-Zeit, then keep turning right (west) until we reach the same courtyard. For Stations 10-14, see Church of the Holy Sepulcher.