Temple Mount

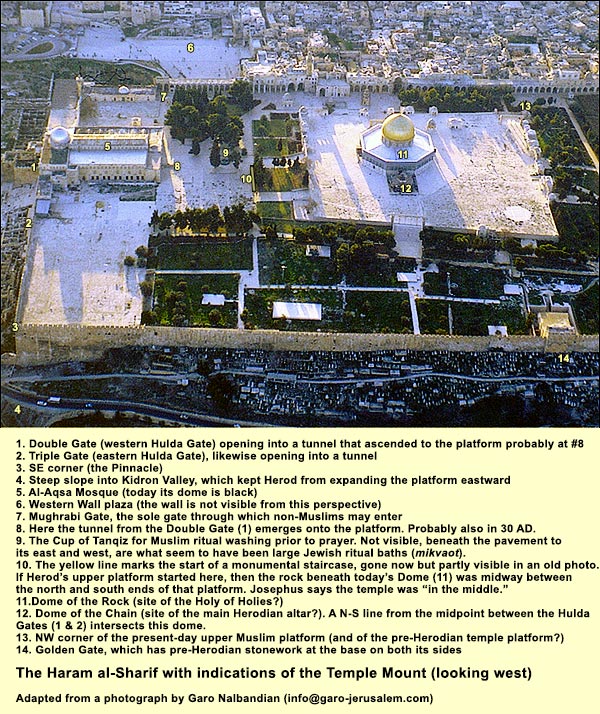

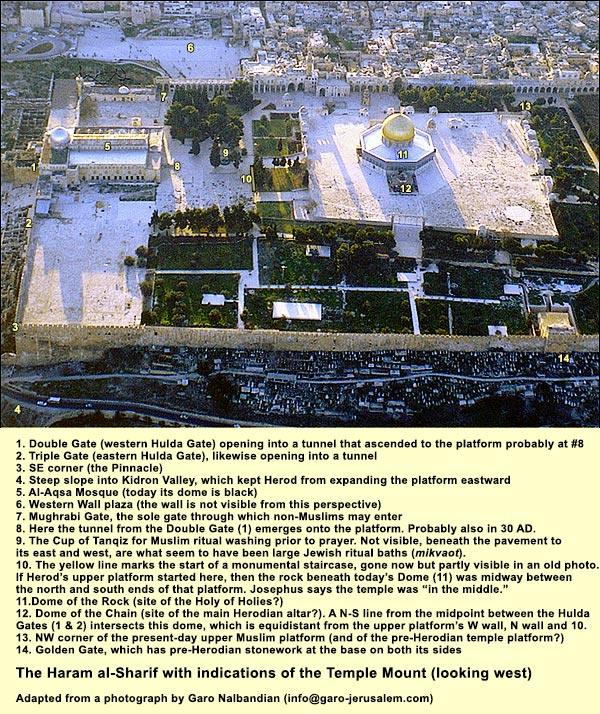

By enlarging the map on the right, you can get a better idea of the natural hill beneath the two platforms.The lower platform on which we stand corresponds in height to the level of the outer court in Herod's Temple. (JacobsonJacobson, David (1). "Sacred Geometry: Unlocking the Secret of the Temple Mount." Biblical Archaeology Review, July/August 1999., p. 60.) It was on this level that Jesus upset the tables of the money-changers (Luke 19:45-46Luke 19:45-46: He entered into the temple, and began to drive out those who bought and sold in it, saying to them, "It is written, 'My house is a house of prayer,' but you have made it a 'den of robbers'!"). E.P. SandersSanders, E.P. Judaism: Practice and Belief, 63 BCE – 66 CE, Philadelphia: Trinity Press, 1992. (pp. 113-114) has imagined what it was like for a Jewish family visiting the Temple. I shall follow his description, putting my additions in parentheses. First, they have money set aside for the pilgrimage: this is the "second tithe" (the first went to the priests). It amounts to a tenth of the year's produce. It is for their own use, but it must be spent in Jerusalem. Let us suppose a set of circumstances: during the year, the wife had a child; she went to her uncle's funeral; the husband cheated a neighbor financially. They cannot, under such conditions, enter the Temple. The woman became impure by giving birth, so she must wait the requisite period (40 days for a son, 80 for a daughter), then take a ritual bath. But she also has corpse impurity. Its removal takes seven days. We'll suppose a priest comes to her village and sprinkles her on the third and seventh days with the requisite mixture of water and ash. As for the man, he has repaid his neighbor and added a fifth. Under these conditions, and provided the wife isn't menstruating, they may take a ritual bath and enter the sacred precinct. They go, then, toward Jerusalem. Surrounded by higher hills, as reflected in Psalm 125:2"Jerusalem - mountains surround her, and YHWH surrounds his people - now and forever more.", the city and its temple come into view quite suddenly, arousing awe. The family sings Psalm 122. If they see the temple from the Mount of Olives in the morning, it blazes like the sun:It was covered all over with plates of gold of great weight, and, at the first rising of the sun, reflected back a very fiery splendor, and made those who forced themselves to look upon it to turn their eyes away, just as they would have done at the sun's own rays. But this temple appeared to strangers, when they were coming to it at a distance, like a mountain covered with snow; for as to those parts of it that were not gilt, they were exceeding white. ( WarWar= Josephus Flavius. The Jewish War. Translated by William Whiston. (Abbreviated in text as War.) V 5.6) Having found lodging or set up camp, the exemplary family members immerse in a public ritual bath and abstain from sex that night. The next day is not yet the festival itself. It is a day when people bring private offerings. In order to buy sacrificial animals, they must have acceptable coinage, namely, Tyrian shekels. Although these have the image of a god named Melqart, they are the coins the priests demand (Mishnah, Berakhot 8.7). Their silver content is over 90%. If you arrive with any other coinage, you have to exchange it for the Tyrian. Hence, the moneychangers. Outside, the family buys a ram for the man's guilt offering and a lamb as a thank offering. Then they approach from the south end, as most pilgrims do. (This is the traditional direction to come from, harking back to Solomon's Temple, when the Jerusalemites lived south of the building.) They go through one of the Hulda Gates and find themselves in a tunnel that leads beneath the Royal Portico and up onto the lower platform. Sanders here has them turn into the Royal Portico, which occupied the south end of the platform, and buy two unblemished doves for the woman's offering after childbirth. (Yet they might have brought them in from outside.) Now they proceed across the court to a balustrade, called the soreg, passing inscriptions warning Gentiles not to go closer on pain of death. One of these inscriptions has been found complete; there is also a fragment of another.

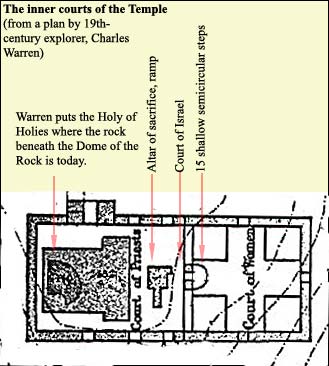

Our imagined family goes past the soreg and ascends the 14 steps. They are not yet at the level of today's upper platform. Not being priests, they head to the right. The woman enters the Court of Women through a gate in the southern protective wall, but here she need not ascend steps, because this far east the level inside is the same (and lower than today's upper platform). She gives her birds to a Levite, explaining that they are for a childbirth. Then she ascends perhaps to a gallery, from which she can watch what the Levite does with them. Her husband goes around the protective wall to the east and then through its eastern gate. He goes straight through the Court of Women, climbing fifteen steps to another gate. These steps, writes Josephus, were "shallower than the five at the other gates." ( Jewish WarThe Jewish War. Translated by G.A. Williamson. Penguin, 1981. V 188-212 [5.3].) They would have brought him to the higher level, corresponding to that of the upper platform today. He enters through the gate to the Court of Israel. Continuing with Sanders' Sanders, E.P. Judaism: Practice and Belief, 63 BCE – 66 CE, Philadelphia: Trinity Press, 1992. account: The man finds a Levite, who takes the lamb and holds it. He brings the ram to a priest, puts his hands on its head, confesses what he did, and explains that he has made restitution to the person he wronged. He and a Levite then lift the animal partly over the parapet dividing the Court of Priests from that of Israel. Josephus says this parapet was eighteen inches high. (The Mishnah puts it at 4.5 feet! Had its authors ever tried lifting an animal?!) The priest places a basin beneath its throat (to collect the blood, which he will pour around the base of the altar). The man pulls back the head of the ram and slits its carotid arteries. Sanders comments: [S]laughter was not an everyday experience. Many people ate fowl once a week, but red meat only a few times a year. Slaughter of a quadruped...was a special occasion: it was anticipated, the senses were sharpened, and the quick flood of blood evoked an emotional response.... The act was surrounded by mystery and awe, and in this respect the Jerusalem temple outdid its pagan counterparts. The days of purification in advance..., the majesty of the setting, the physical actions -- selecting fat, unblemished victims, seeing them inspected by experts, walking with them to within a few yards of the flaming altar, handing them over, laying hands on the head,confessing... dedicating the animal, slitting its throat, or even just holding it -- these guaranteed the meaningfulness and awesomeness of the moment. ( SandersSanders, E.P. Judaism: Practice and Belief, 63 BCE – 66 CE, Philadelphia: Trinity Press, 1992., pp. 114-116.) After pouring the blood at the altar, the priest takes the ram away to butcher. The man takes the lamb from the Levite. Another priest comes with a basin, and they slaughter the lamb. Meanwhile, the woman's Levite has found a priest to sacrifice the two birds. Perhaps ten minutes later, says Sanders, the priest who had taken the lamb, which was a thank offering, brings the meat back. The man waves its breast before the altar, then hands it together with the right thigh to the priest. He leaves with the rest of the meat, meeting his wife, who has been watching from the gallery. They go to the campsite and join their friends for the feast. {mospagebreak title=First Temple}Where was the First Temple?The Book of Genesis (22:7 -14) tells us that the near-sacrifice of Isaac occurred on the Mountain of Yahweh in "the land of Moriah": And Isaac said, "Here is the fire and the wood, but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?" And Abraham said, "God will provide [yireh] Himself with the lamb for burnt offering, my son. They come to the place. Abraham builds the altar, arranges the wood, ties Isaac up, and places him on the altar. He takes the knife. But the angel of Yahweh called to him out of the sky, and said, "Abraham, Abraham!" He said, "Here I am." He said, "Don’t lay your hand on the boy, neither do anything to him. For now I know that you fear God, since you have not withheld your son, your only son, from me." Abraham lifted up his eyes, and looked, and saw that behind him was a ram caught in the thicket by his horns. Abraham went and took the ram, and offered him up for a burnt offering instead of his son. Abraham called the name of that place Yahweh-yireh ["will provide"]. As it is said to this day, "On Yahweh’s mountain, yera'eh ["it will be provided"].” The Samaritans identify Yahweh's mountain with Gerizim, but the post-exilic writer of Chronicles (2 Chron. 3:1)Then Solomon began to build the house of Yahweh at Jerusalem on Mount Moriah, where Yahweh appeared to David his father, which he prepared in the place that David had appointed, in the threshing floor of Ornan the Jebusite. puts it in Jerusalem.

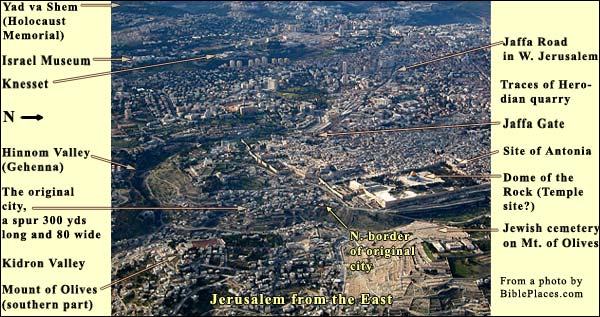

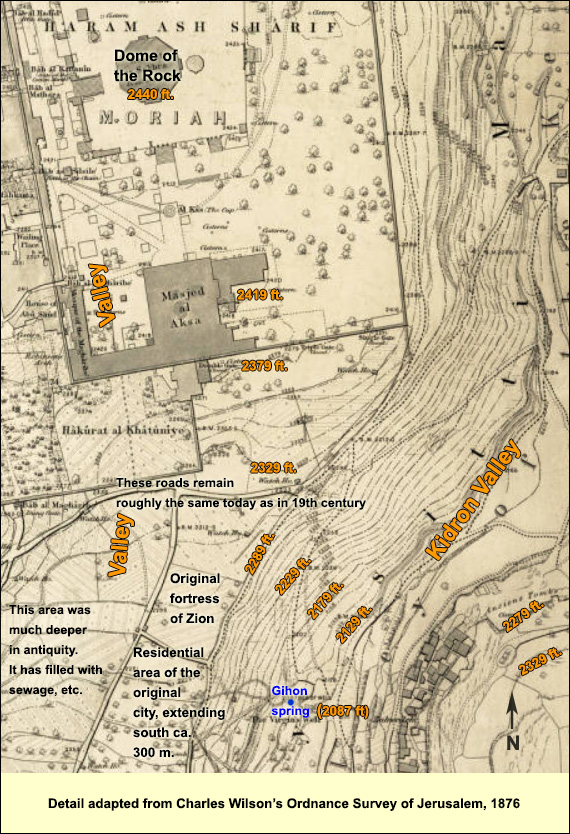

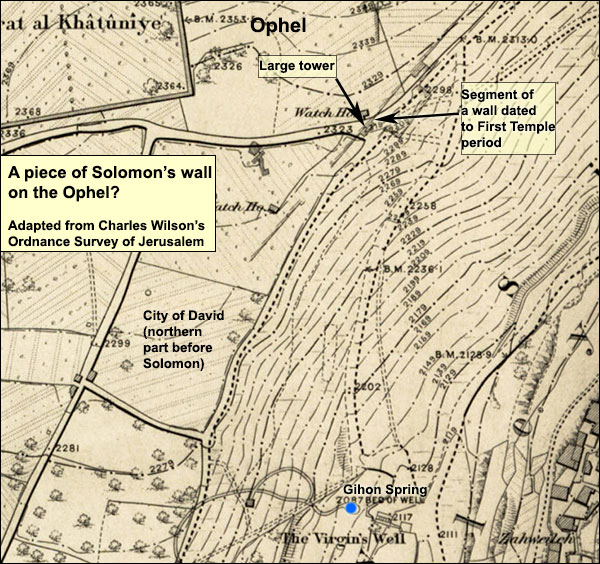

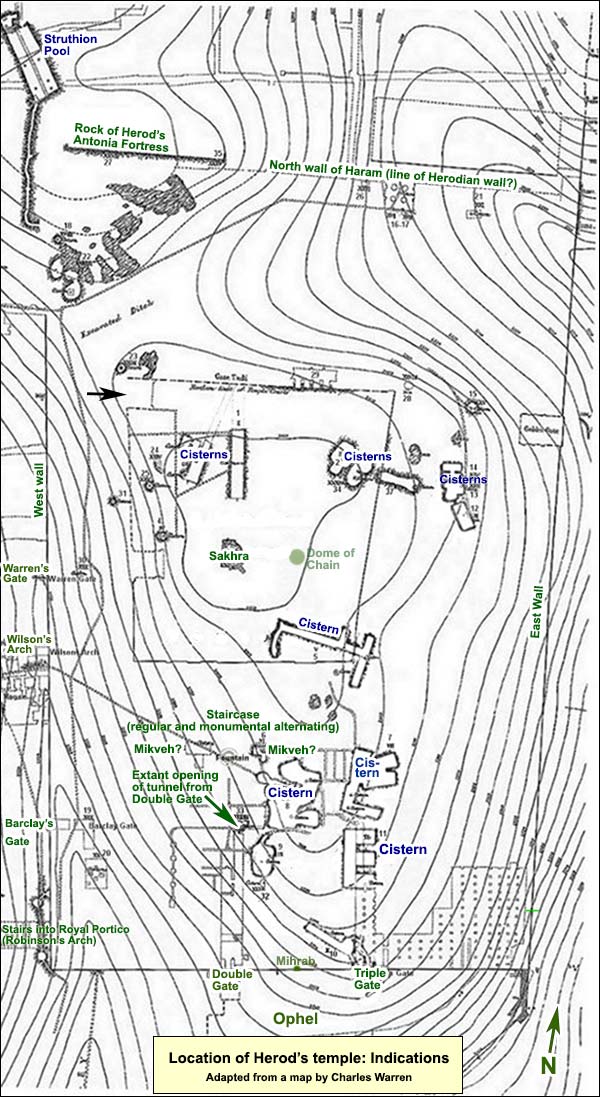

Whether or not we can relate Mount Moriah to Jerusalem, there were additional reasons to build the temple here. For during the city's first eight centuries, the Jerusalemites lived on this hill alone - albeit farther down, on the narrower spur to the south, near the spring. (Details) Here, however, on the peak, was the outcropping of bedrock that today gives the Dome its name. Perhaps it exerted a numinous power. Admittedly, though, the rock is nowhere mentioned in our sources until 333 AD, if then.In the Mishna, compiled in 200 AD, we read: "After the Ark was taken away, a stone [Heb. even, pronounced to rhyme with "heaven"] from the days of the Early Prophets was left standing there [in the Holy of Holies] three fingerbreadths above the ground, and it was called shetiyah [foundation], and on it the High Priest would place the pan of glowing coals." (Mishnah, Tractate Yoma 5.2.) But this stone was probably not the rock beneath the Dome. One would not say of bedrock (sela in Hebrew, not even) that it was "left standing there" or that it was "above the ground." Bedrock is part of the ground. Later, in 333 AD, the Bordeaux Pilgrim writes that in his time the Jews were allowed to enter the city once a year to weep for the Temple at a rock with a hole in it. The rock under the Dome does in fact have a hole that leads down into a cave. It is possible that the pre-Israelite denizens of the city worshipped from this hill, facing west as the Israelites later would. For the name "Jerusalem" means not "city of peace," as popular etymology has it, but a place "founded by Salem," the Canaanite god of the setting sun. KeelOthmar Keel, Die Geschichte Jerusalems und die Entstehung des Monotheismus, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007, pp. 274-75. proposes that, under Egyptian influence, the pre-Davidic Jerusalemites had an open-air sanctuary to the sun-god here; he also holds that the easterly orientation of Solomon's temple perpetuated this tradition.Indeed, David must have established an accord with Jerusalem's earlier inhabitants, the Jebusites, for he goes "up" and buys the threshing floor of Arauna the Jebusite, erecting a sacrificial altar there ( 2 Samuel 24: 24 - 25The king said to Araunah, "No, but I will most certainly buy it from you for a price. I will not offer burnt offerings to Yahweh my God which cost me nothing." So David bought the threshing floor and the oxen for fifty shekels of silver. David built an altar to Yahweh there, and sacrificed burnt offerings and peace offerings"). The passage does not say where this threshing floor was, but the area of the rock is windy enough. If we accept the account in 1 Kings 6 and 7, Solomon's palace was bigger than the temple. The palace was 100 cubits A cubit is about half a meter long, or the distance from the elbow to the edge of the fist; to be exact, in Egypt a short cubit was 45 cm., a royal cubit 52.5 cm. or 20.67 inches long, 50 wide, and 30 high, taking 13 years to build. The temple, by contrast, was 60 cubits long by 20 wide and 30 high, taking 7 years. (A note on the height.) The Hebrew of 2 Chronicles 3:4 (written centuries after Kings) puts the height of the temple's portico at 120 cubits, but this would have distorted the proportions; some Septuagint and Syriac manuscripts have "20" instead of "120": "20" is closer to 1 Kings 6:2, which should be preferred. The arrangement of these buildings is not stated, although it is clear from 1 Kings 7: 21 that the temple faced east. There would not have been space for such large edifices in the City of David, which was below to the south. Because of the deep valleys, the only room for that original city's expansion was to the north. No trace of palace or temple (or of anything, almost, from the First Temple period) has been found in the OphelThe area between the Temple Mount and the City of David. See below. excavations, so we are left with the space beneath Herod's temple platform. This is under the civil control of the Muslim Supreme Council (Waqf). Even if the Waqf permitted digging, however, it is doubtful whether any structural remains from the early time would turn up. The area underwent radical rebuilding by Herod. Furthermore, for centuries after the destruction of 70 AD - until the 7th-century Muslims cleaned it up and erected their sanctuaries - it was exploited as a source of building stones and as farmland.Before Solomon's palace and temple were built, the hill would have afforded an ideal place from which to attack the city, as we can see in the contour lines that Charles Warren and Charles WilsonCharles Warren received permission from the Ottoman vizier to dig vertical shafts and horizontal galleries between them, mostly on the Haram's perimeter. The meticulous drawings and descriptions by him and Charles Wilson (1867-70) are still our only source of information for many areas. were able to establish:

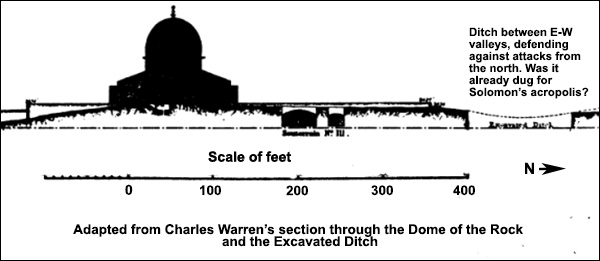

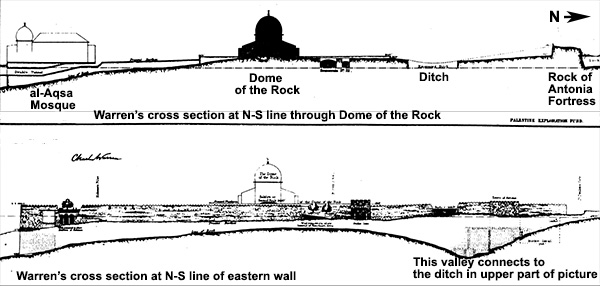

The building of the palace and temple near the peak may have been, in part, an act of fortification. The amply level area around today's Dome of the Rock was partly defended against attack from the north by valleys entering from east and west. You can see them by enlarging the map on the right, (which is mainly devoted to the cisterns and water supply). The valleys fail to unite, but precisely in the stretch between them, Wilson and Warren,Wilson, C. and C. Warren, The Recovery of Jerusalem: A Narrative of Exploration and Discovery in the City and the Holy Land. London: Richard Bentley, 1871, p. 13. saw that "the rock gives place to turf, and there are other indications which would lead us to believe that there was at one time a ditch cut in the solid rock.” The ditch would have helped to protect a pre-Herodian Temple. StraboGreek historian and geographer (64 BC-21 AD) mentions this ditch in his Geography XVI Par. 40, saying that Pompey filled it in order to conquer the temple in 63 BC. He tells us it was 60 feet deep and 250 feet wide. Josephus also mentionsWar I Ch. 7, Par. 3 Pompey's filling of the ditch, saying that the Romans did the work on the Sabbaths, when the Jews refrained from fighting if not attacked. (One wonders whether the same method might have been used by the Romans when they built the assault ramp at Masada in 73 AD.)Here is a cross-section of the Haram (with scale) by Warren:

And here are broader views, the first showing more of the natural hill as it appears at a N-S line running through the Dome, the bottom one showing the depth of the valley at a N-S line running through the Haram's eastern wall:

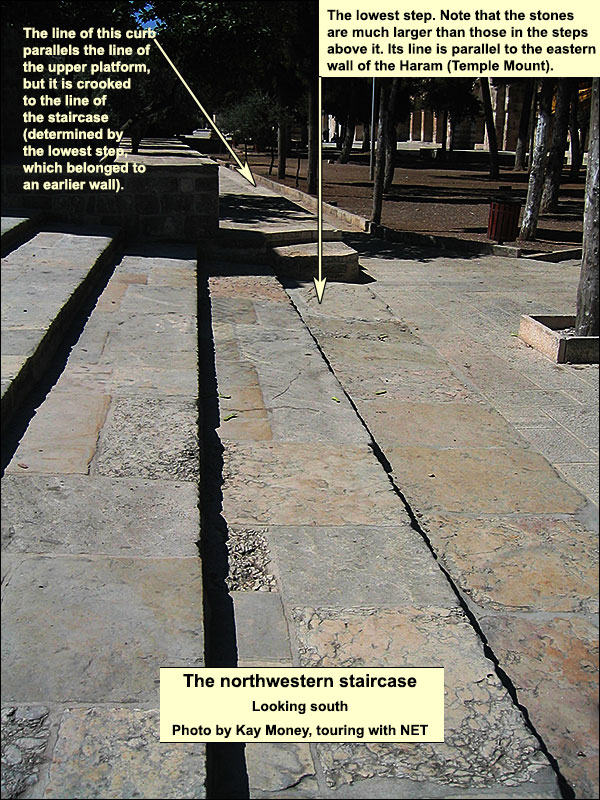

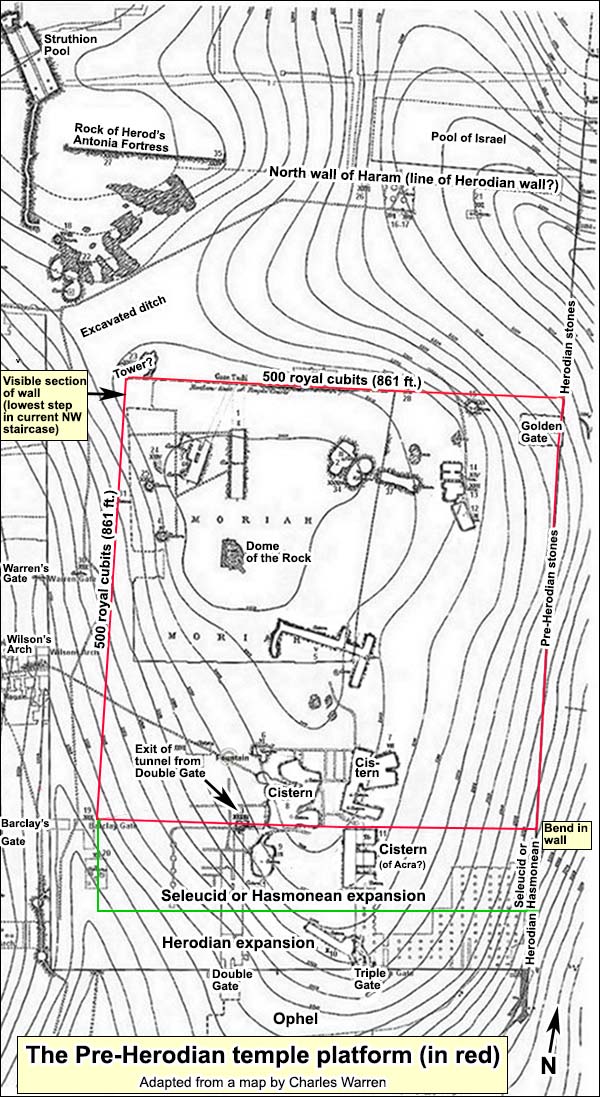

As to what the ditch defended, an ancient square platform has been discerned in the Haram by Leen Ritmeyer.Ritmeyer, Leen. “Locating the Original Temple Mount.” Biblical Archaeology Review, Mar/Apr 1992, 24-26, 29, 32-45, 64-65. http://members.bib-arch.org/publication.asp?PubID=BSBA&Volume=18&Issue=2&ArticleID=1. In order to link this platform with the First Temple, however, we must assume with Ritmeyer that those who built the Second, starting in 520 BC (66 years after the First was destroyed), would not have had the resources to erect the walls from scratch - rather they would have built upon what remained of the earlier walls. As said above, 1 Kings 7 indicates that the platform of the First Temple included a palace that was bigger than the temple. In his reconstruction (summarized below), Ritmeyer does not include the palace on the platform, apparently because he follows the account in the Mishna. But the Mishna purports to describe the Second Temple, not the First, and it was compiled around 200 AD, seven centuries after the palace had last been seen on the mountain. In short, if the following reconstruction pertains indeed to the First Temple period, then we should envision, on the platform, both palace and temple. Ritmeyer's reconstruction of the ancient platform begins about 15 meters south of the excavated ditch, at the lowest step in the northwest staircase leading down from the present-day upper platform. (To locate the staircase, consult the map below.) It was archaeologist Benjamin Mazar, Ritmeyer's mentor, who first noticed something peculiar about this step: its stones are much larger than those in the steps above it. On one of them, in fact, a margin and a protruding boss were once partly visible (they are no longer so, because the adjacent pavement has been raised). A colleague of Ritmeyer's also pointed out that this lowest step (and hence its whole staircase) does not line up with the wall of the present-day platform as do the other staircases. Instead, it is parallel to the Haram's eastern wall. Here is a photograph of the step in context, followed by a closer look at its ashlars:Rectangular dressed stones

For a closer look at the stones in the lowest step, please enlarge the photo on the right. At a point near the northern edge of this step, the big stones cease and we find small ones as on the steps above. Ritmeyer noted that "the northern end of the northernmost large stone of this step was exactly in line with the northern edge of the raised Muslim Platform." It is also in line with a cut scarp (observed by Charles Warren), on which the northern edge of the Muslim platform is built. If we continue this line to the east, we reach a point in the eastern wall a bit north of the Golden Gate. The distance from the stone in the lowest step to the eastern wall is 500 royal cubits (861 feet, such a cubit being 20.67 inches long). This is a remarkable finding, because in Ezekiel's vision of the future temple, as well as in the Mishnah, the temple platform is presented as a square with 500 cubits per side. Below is Ezekiel 42:15-20. Where I have put "cubits," the standard Hebrew version has the word for "reeds"; for this alteration, see Milgrom and Block, p. 101, n. 268.See Jacob Milgrom and Daniel I. Block, Ezekiel's Hope: A Commentary on Ezekiel 38 - 48. Cascade Books, 2012. Now when he had finished measuring the inner house, he brought me out by the way of the gate which faces toward the east, and measured it all around. He measured on the east side with the measuring reed five hundred cubits, with the measuring reed all around. He measured on the north side five hundred cubits with the measuring reed all around. He measured on the south side five hundred cubits with the measuring reed. He turned about to the west side, and measured five hundred cubits with the measuring reed. He measured it on the four sides. It had a wall around it, the length five hundred, and the width five hundred, to make a separation between that which was holy and that which was common.The 500-cubit line from the northwest staircase reaches the Haram's eastern wall at the point where, in the wall's lower parts, Warren saw the beginning of Herod's northward extension (see the map below). The stones in the lower levels south of this point belong to the older wall of the platform. Herod, be it noted, could not expand the platform eastward, because the slope of the Kidron Valley is too steep, so he used the older wall, extending it to the north and south.

If we now follow this eastern wall to the south for 500 royal cubits, we come to a slight bend (not visible from a distance), which is 240 feet north of the southeast corner (again, see the map below). South of this bend, in the lower parts, is masonry usually identified as Hasmonean, although Yoram Tsafrir"The Location of the Seleucid Akra in Jerusalem" (in Hebrew). Cathedra, Jerusalem: Yad Yizthak Ben-Zvi, 14: 17–40. suggests that it belonged to the wall of the Seleucid Acra.The location of this citadel is disputed. The Acra was a nuisance for the Hasmoneans: even after they had reconquered Jerusalem and rededicated the temple in 164 BC, the Seleucids continued to hold it. Only in 141 BC did Simon Maccabee starve them into leaving. Like Tsafrir, Ritmeyer proposes that the Acra was just south of the then temple platform (in red below) and that the E-shaped cistern belonged to it. In any case, it is evidence of expansion in the 2nd century BC, and it is followed by Herod's extension, which stretches southward 106 feet to the present-day corner. We do not know whether the masonry changes north of the bend, because in the lower level, where the Seleucid or Hasmonean stones are, Warren did not penetrate far enough to the north, and the political situation has precluded further underground exploration. Nevertheless, Ritmeyer has managed to study two visible stones that are just above ground slightly north of the bend, and he dates them to the time of Hezekiah.

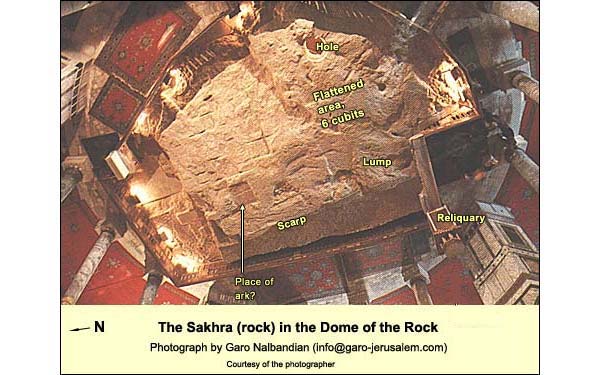

From the bend we go west, keeping parallel to the northern line and staying ever so slightly north of the E-shaped cistern (which Ritmeyer suggests belonged to the Acra). At 500 cubits we reach a point intersected by a 500-cubit-long line from our starting point (namely, from the lowest step of the northwest staircase). This point (see the map above) is situated where the eastward ascent to Herod's platform from Barclay's Gate made a 90 degree turn to the south. Ritmeyer proposes that Herod's builders did not want to break through the Seleucid or Hasmonean wall (in green on the map) and so they built the turn. In this way we complete a square of 500 royal cubits on each side. As said above, that is exactly the number given in Ezekiel 42:15-20. Was this vision inspired by the exiled prophet's memory of the First Temple? Or should we suppose, contra Ritmeyer, that the platform did not belong to the First Temple at all, but rather that it was built by the returnees, starting in 520 BC, in deliberate accord with Ezekiel? This too is possible.The 500-cubit square is also present in the Mishnah. Its authors were presumably describing the last temple (they do not say otherwise), whose Herodian sides were much longer than 500 cubits. Perhaps they meant the part of Herod's temple into which only Jews were permitted, and perhaps this coincided with the older 500-cubit square described above. We note at the bottom of the above map, in this connection, that the tunnels from the double and triple gates emerge into daylight precisely on the southern line of the 500-cubit platform. Perhaps these gates were intended only for Jews who, having just taken the obligatory ritual bath, wanted to enter directly into the pure area. Gentiles could have entered the impure area by the western gates. But can we get any closer to the First Temple? Josephus (War V 5.1Josephus Flavius. The Jewish War.) ) indicates that Solomon's temple was built on the top of the hill: Now this temple, as I have already said, was built upon a strong hill. At first the plain at the top was hardly sufficient for the holy house and the altar, for the ground about it was very uneven, and like a precipice; but when king Solomon, who was the person that built the temple, had built a wall to it on its east side, there was then added one cloister [portico] founded on a bank cast up for it, and on the other parts the holy house stood naked. But in future ages the people added new banks, and the hill became a larger plain.Yet how did Josephus know where Solomon's temple was? He doesn't say. He may have been "reading back" from Herod's, which he did know. We might attempt to justify this method as follows: Between the first temple, destroyed in 586 BC, and the second, commenced in 520, there were always Jerusalemites living hereSee for instance Oded Lipschitz, The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem: Judah under Babylonian rule, Eisenbrauns 2005 who could point to the site. When the Jews began building the Second Temple, they would presumably have done so on the place of the First. In turn, that would have been the site of Herod's grander version, which Josephus knew. There is a hitch in the logic, however. If 1 Kings 6 and 7 are accepted as historical, then the king's palace overshadowed the temple. (Note that Josephus does not locate Solomon's palace on this hill.) After the return from the Babylonian exile, Jerusalem had no king - hence no need for a palace. Only a temple was built. This major change might well have occasioned a corresponding change in the layout. As to the 500-cubit-square platform, supposing that it did belong to the First Temple, the question remains as to which king of Judah built it - and dug its defensive ditch. In his book The Quest, Ritmeyer nominates Hezekiah, allowing, however, that a definitive answer requires excavation.The Holy of HoliesThe Holy of Holies may have been where the Dome of the Rock is. From 1 Kings 6:16, we know it was at the western extremity of Solomon's temple. As the contour maps show (see above), you could not go more than a few yards west of the rock without sliding downhill.Leen Ritmeyer has noticed a few tantalizing features of the rock. There are cuttings all over: perhaps the rock was quarried for building stones. Yet several cuttings may be ancient, and these arouse special interest. Let us stand near the reliquary, on the western side looking east (use the picture below); between us and the hole in the rock (which Ritmeyer calls Crusader, ignoring the Bordeaux pilgrim of 333), we see sections that someone cut flat. The total width of these flat sections, north to south, is 10 feet, 4 inches: 6 royal Egyptian cubits. Ritmeyer thinks that these were foundation trenches for building stones. According to the Mishnah, the walls of the Holy of Holies were 6 cubits thick.

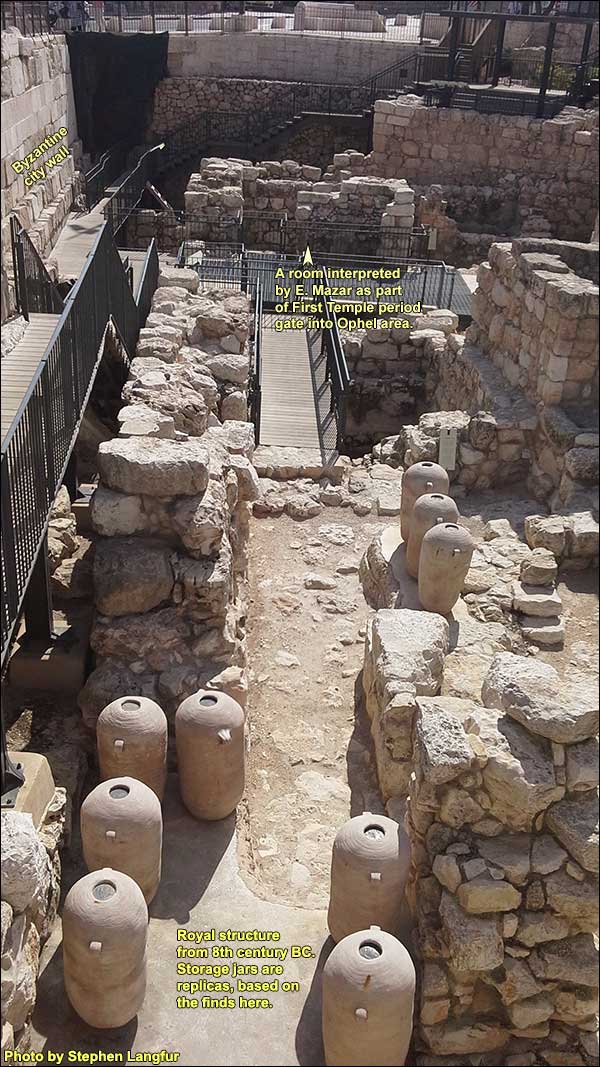

Still using the picture above, let us try to imagine this wall. Note that the "foundation trenches" do not continue all the way to the point where the western wall of the Holy of Holies would have been. There is an awkward upwelling of stone just east of the reliquary. On Ritmeyer's theory, this area too should be flat.Apart from that, the theory works nicely -- and harbors another surprise. Having imagined this southern wall of the Holy of Holies, let us picture its western wall (starting about where the reliquary is) and its northern one, of equal length, as well as the curtain on the east. The result is the biblical square with 20 cubits on each side. Looking at the rock from above, we find in the center a rectangular cut, perpendicular to the western scarp. Ritmeyer estimates it as 1.5 by 2.5 royal cubits. These are the dimensions of the Ark of the Covenant (Exodus 25:10Exodus 25:10:“They shall construct an ark of acacia wood two and a half cubits long, and one and a half cubits wide, and one and a half cubits high.”).Ritmeyer's theory is at once exciting and exasperating. He may have found the place of the ark. There remains the problem of the awkward lump, mentioned above. And the rock has been so chipped away! Beginning a few feet to the east of the putative "cutting for the ark," we can see, as the rock slopes down, the traces of a series of cuttings with a similar form and axis. Along with the supposed "foundation trenches," these traces leave the impression of quarrying. So does the sudden drop on its north side. The "cutting for the ark" may be the impression left by a quarried stone. Or perhaps it was the cutting for the ark.At the time of the Second Temple (515 BC - 70 AD), no ark was present in the Holy of Holies. Furthermore, if the Second Temple was built here, then according to the height-measurements in Josephus and the Mishna, the rock would have been beneath the floor (see David Jacobson.)(See Jacobson, David (1). "Sacred Geometry: Unlocking the Secret of the Temple Mount." Biblical Archaeology Review, July/August 1999. This would indicate that the builders had no scruples about placing pavement over the rock, so perhaps it did not exert such numinous power as to determine the site of the temple, First or Second. We recall that the rock goes unmentioned in the sources before 333 AD. Why then should we believe that the temple or altar were ever built on it? More puzzlesConsider the area of the Ophel by enlarging the picture on the right. Extensive excavations were carried out on the Ophel for a decade after the 1967 War, yielding very little from the First Temple period, although much from Herod's time and later. Nevertheless, a few First Temple vessels did turn up at the bottom of a cistern near the Second Temple's southern retaining wall. Another exception was in the area near the modern road. Here in 1976 archaeologists Benjamin Mazar and Meir Ben Dov found part of a public building, pictured here, containing vessels that had been charred in the destruction of 586 BC. A decade later Mazar's granddaughter, Eilat, continued the dig. On the basis of the pottery, she dated the floor to the end of the 8th century. This floor had been preceded by an earlier one. The fill beneath the latter yielded very little pottery, but between two foundation stones she found a black juglet, intact, that fits into the palm of a hand. Its type was used in the 10th and 9th centuries BC. It may have been an heirloom, placed between the stones as a kind of votive offering. On this basis, she first dated the lower floor - and the original building - to the 9th or early 8th centuries. This does not bring us back as far as Solomon, but she has since revised her view, taking the juglet as evidence for a 10th century - Solomonic - date.

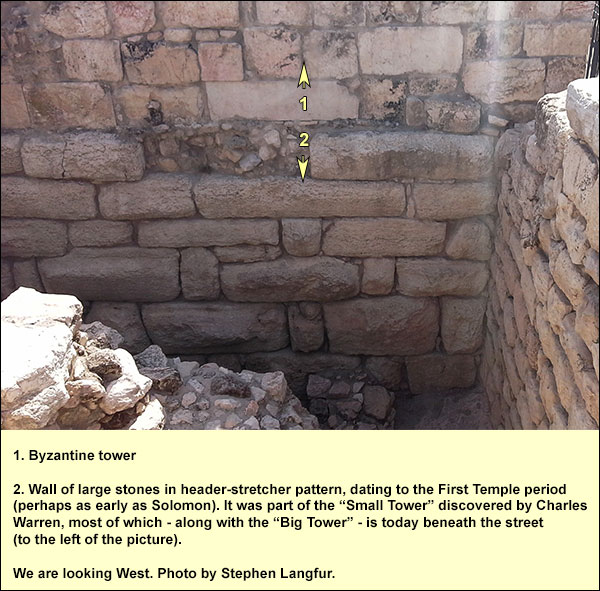

A few meters to the south and east, furthermore, are two towersThe towers are still mostly underground, the larger of them stretching to the other side of the modern road. discovered by Charles Warren in the 19th century. Beneath the smaller of them, in 1967, Kathleen Kenyon found masonry consisting of large stones laid in a header-stretcher pattern, pictured here as "2":

Eilat Mazar interprets this segment as part of the wall attributed to Solomon in 1 Kings 9: 15.And this is the levy that King Solomon raised in order to build the House of Yahweh and his own house and the Millo and the wall of Jerusalem, as well as Hazor, Megiddo, and Gezer. The segment was not necessarily part of a tower, although the smaller tower later incorporated it. The larger may be the "projecting tower" referred to in Nehemiah 3: 24-27.After him Binnui the son of Henadad repaired another portion, from the house of Azariah to the turning and to the corner. Palal the son of Uzai repaired opposite the turning and the tower that projects outward from the upper house of the king, which is by the court of the guard. After him, Pedaiah son of Parosh repaired. And the Nethinim used to live in the Ophel, to a point opposite the Water Gate on the east and the projecting tower. After him the Tekoans repaired another portion, from opposite the big projecting tower until the wall of the Ophel.

If we grant a Solomonic date for some of the sections that the Mazars and Ben Dov uncovered, we still have the question as to why the rest of the Ophel is so scarce on remains from before the 8th century BC. One does not like an argument from silence, but given the amount of digging that has been done in the Ophel, the silence here is deafening. Strategically, it would not have made sense to build the palace and temple above, where the Dome of the Rock is today, while leaving an empty space between the acropolis and the rest of the city. An enemy could easily take the waterless acropolis and use its buildings as fortresses while attacking the City of David. In favor of the biblical account, we may raise two observations. First, yes, the silence is deafening, but in a mountain city like Jerusalem - to quote the adage - "Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence." The intensive building activity on the Ophel under Herod and later the Omayyads might well have shaved away any First Temple foundations and with them any chance of finding First Temple pottery in situ. (Some was found in earth-fills between later walls, but this is not evidence, for it could have been carted in.) Second, the old fortress of Zion, south of the Ophel, apparently became irrelevant in the 10th century BC, so the city probably expanded northward then, as implied by the biblical account together with geographical logic. {mospagebreak title=Second Temple}Where was the Second Temple?We cannot be sure whether the square of 500 royal cubits per side belonged to the First Temple, but we may be confident that it belonged at least to the pre-Herodian Second. The reasoning is simple: (1) The Mishna describes a square of 500 cubits on each side, and it can hardly be a coincidence that if we draw a line from the present-day platform's northwest step, which has exceptionally large stones, to the Haram's east wall, the length turns out to be 500 royal cubits. (2) The literary sources indicate nothing, after the time of the First Temple, to which this square could have belonged - except the early Second Temple. Besides, we have read that Pompey, in order to conquer the temple in 63 BC, had to fill a moat on the north side. If this was the ditch detected by Warren (see his map), it was exactly in the right position to defend the 500-cubit platform. We have also seen that the platform was expanded to the south either by the Seleucids or the Hasmoneans. In the portion south of this expansion, however, we encounter a problem:

In 2011, archaeologists Eli Shukron and Ronny Reich dug down to bedrock near the southwest corner of the Temple Mount. They discovered various rock-cut installations that had belonged to buildings earlier than Herod's temple. One of them was identified as a ritual bath, in Hebrew a mikveh. The temple builders had filled it, topped it with three large flat stones, and laid the western wall's first course over part of it. The archaeologists of 2011 removed fill from the part of the mikveh that was not beneath this wall's foundation stones. They unearthed three clay oil lamps that were typical of the 1st century AD. They also found coins, of which the latest four had been minted by the Roman prefect Valerius Gratus in 17 - 18 AD. (For an account by the Israel Antiquities Authority, see here.) The excavators concluded that this section of the Western Wall could not have been built under Herod, who died in 4 BC. This conclusion, which received worldwide publicity, would imply a post-Herodian date not only for the southern end of the western wall, but also for the royal portico that stretched eastward for 920 feet from this southern end. Josephus wrote,Antiquities XV Ch. 11, Par. 5 "this cloister deserves to be mentioned better than any other under the sun." Its roof would have been about as high as the top of the dome of al-Aqsa today. It had four rows of columns, 162 in all, making three aisles. On either side of the middle aisle, the columns were 27 feet high and so thick that it took three adults to surround them. By comparison, the columns of Italian marble in al-Aqsa, including the capitals, rise 15 feet; the central ceiling, however, is about as high as the original pillars would have been. In accordance with the coins of Gratus, we would also have to redate the Double and Triple ("Hulda") Gates in the southern wall, as well as the grand staircase. The redating would undermine Josephus' account,Antiquities XV, Chapter 11, Paragraphs 3, 5, and 6; see also his The Jewish War I Ch. 21 Par. 1for he tells us that Herod celebrated the completion of the temple, including the magnificent royal portico on the south. Finally, one may question whether so huge a structure could have been built during the rule of a Roman procurator. And why, in such a case, would Josephus have called it "royal," given that the last king, Herod, had died more than 20 years earlier? If the portico's funder had been a Jewish ruler, namely, Herod's grandson Agrippa (r. 40 - 43 AD) or his son Agrippa II (who was made responsible for the temple in 48 AD), surely Josephus, born in 36 AD, would have known as much and said so.Admittedly, we read in John 2:20 that the construction of the temple, which began ca. 20 BC, took 46 years, and Josephus reportsAntiquities, Book XX, Ch. 9, Par. 7that it was completed in 63 AD. This left 18,000 workers idle, he says, and Agrippa II had the city repaved in order to provide jobs. (As often with Josephus, one suspects that a copyist added a zero to the demographic data.) But we have always had these passages, and they never stopped us from attributing the main structures to Herod, including the royal portico. Do the coins of Gratus compel a redating?These coins, as said, were not found under the wall's foundation stones. In a recent comment, Leen Ritmeyer notes: "Actually the coins prove nothing at all, as the mikveh only project[s] a few centimeters under the wall. The coins came probably from a later repair." For instance, the street beside the wall shows no sign of use, so it was probably one of those repaved by Agrippa II, seven years before the temple's destruction. Given these doubts about the proposed re-dating, I shall continue to assume that the temple's main structures were Herodian, including the royal portico and the outermost southwest corner. This assumption guides the following text.What then do we know about the location of Herod's temple? There is no doubt that the great surrounding walls belonged it, for the following reasons. Apart from Josephus' description, there is a Hebrew inscription carved into a stone from the uppermost southwest corner (i.e., found lying directly on the pavement, hence among the first stones to have been battered down). This reads, "For the place of the trumpeting." It corresponds to a passage in Josephus,War IV Ch. 9 Par. 12 who wrote of a place at the top of the temple "opposite the lower city," where "one of the priests stood of course, and gave a signal beforehand, with a trumpet at the beginning of every seventh day, in the evening twilight, as also at the evening when that day was finished, as giving notice to the people when they were to leave off work, and when they were to go to work again."

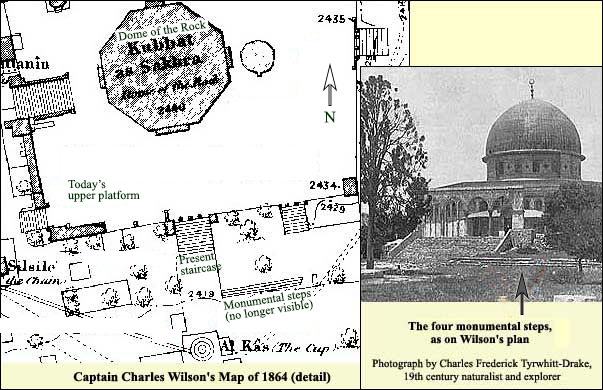

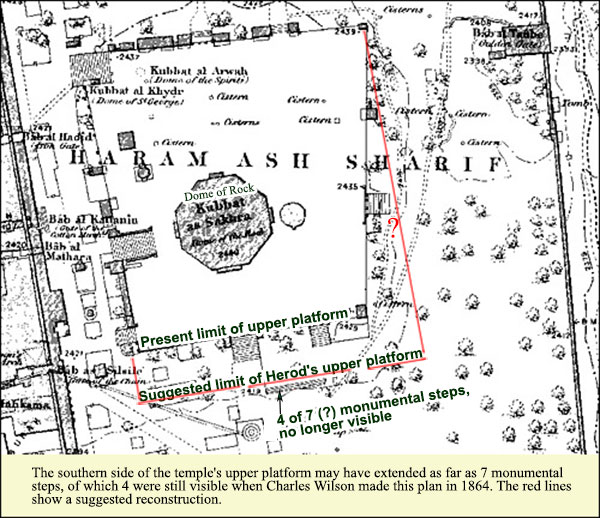

The walls compose an irregular quadrilateral of 920 feet on the south, 1590 on the west, 1033 on the north, and 1509 on the east. They enclose 36 acres (144,000 square meters or 20 soccer fields by the FIFA standard). In its time this was the largest temenossacred enclosure ever built. It took up a fifth of the city before 66 AD. Judging from the stones that were batterred down (found on the ancient street beneath the western retaining wall), we may conclude that the design was similar to that of the much smaller temenos in Hebron, which is also attributed to Herod (although Josephus does not mention it).Within the great walls, then, where would the temple have been? We may assume that the builders of the first Second Temple, who started work in 520 BC, would have known the location of the First and would have set their version in the same area. As we have seen, this would have been in the broad level area near the present Dome of the Rock. In the time of the First Temple, however, the king's palace was also here, and it, not the temple, was the dominant building. Since the lack of a king made a palace irrelevant in 520 BC, the temple had this area to itself, and so the builders probably placed it more centrally. We are aided, on this question, by an old photograph and a map. (For what follows, see Jacobson,Jacobson, David (1). "Sacred Geometry: Unlocking the Secret of the Temple Mount." Biblical Archaeology Review, July/August 1999.to whom I am indebted for much of this description. -- SL) Charles Wilson made a map of the Haram in 1864, and on it we can see a flight of 4 steps that has since disappeared. There is also an old photograph showing these steps.

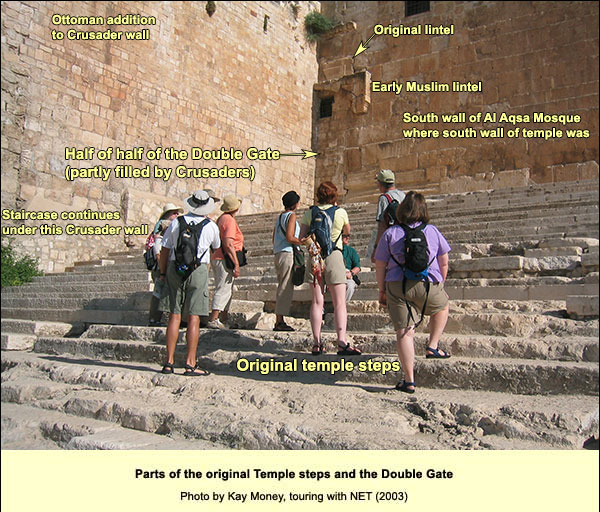

To judge from the photograph and Wilson's map, the steps were probably too high for human comfort. There are examples in classical Greek temples of such high steps (perhaps for the god); the pattern is typically interrupted by flights of shallower steps, friendly to mortals.A broad Herodian staircase has been unearthed before the Double Gate (the westernmost of the two Hulda Gates) in the southern retaining wall. Its steps are parallel to the four on Wilson's plan. They are, however, mortal-friendly.

Near the four high steps on Wilson's map, there must also have been a staircase of mortal-friendly steps. Josephus wrote there were 14 steps from the lower platform to a terrace or rampart (hel ). (The Mishnah said 12.) These would have been the friendlier steps.The terrace was 15 feet deep, says Josephus (and the Mishnah too). Then, he writes, came a high protective wall with gates in it. One ascended to these gates by another 5 steps. That would bring us to the level of the Court of the Priests, but still not to the height of the upper platform as it is today. Another 12 steps led up from the Court of the Priests to the floor of the sanctuary, which (figuring half a cubit per step, as the Mishnah has it) would have been slightly higher than the present platform.If we look at Wilson's map of the Haram (below), we see that the Dome of the Rock appears off center. If it is standing where the Herodian temple was, the latter must have seemed central enough for Josephus to remark that it was "in the middle" (Jewish WarThe Jewish War. Translated by G.A. Williamson. Penguin, 1981.V 188-212 [5.4]). Supposing therefore that the southern edge of the upper platform was south of where it is today, namely, at the top of the staircase that included the four steps on Wilson's plan, we would have indeed a more symmetrical impression, in keeping with Josephus.

There is another interesting feature. Of the great walls, the eastern and the western are not parallel. This is because the major part of the eastern wall goes back (probably) to the time of the First Temple (and certainly to the pre-Herodian Second). Herod could not build a new wall further to the east, because the Kidron Valley was too steep and deep (serving as a natural glacis). He therefore adopted the existing eastern wall, which makes an angle of 92 degrees to his new southern wall (rather than 90 degrees as in all the corners of the Hebron temenos). But why didn't he place the southern wall differently in order to get a perfect right angle? The answer has to do with his plan for the city as a whole: the streets appear to have been in a grid pattern,See John Wilkinson, Jerusalem as Jesus knew it: Archaeology as evidence, London: Thames and Hudson, 1978, pp. 53-65. i.e., either parallel or perpendicular to one another. The temple mount's southern and western walls were built in accordance with the grid, but the eastern wall, as said, could not be changed. And the north wall of the temple mount? Here we lack the courses of stone that enable identification with Herod. The north wall might have stretched along the line of the present-day Haram wall, or it might have kept to the grid pattern, intersecting the east wall at a point north of where the Haram wall does. At this point, Charles Warren noted, the Herodian courses in the eastern wall come to an end! I am tempted, therefore, to follow Jacobson in moving the north wall a bit. On the other hand, the change would leave the southeast corner of a great block of bedrock sticking awkwardly into the temple area. This is the block on which the Antonia Fortress had been built by Herod, probably a decade or so before he started rebuilding the temple.Mark Antony, enemy to Octavian (later called Augustus), died after being defeated at Actium in 31 BC; following that date, Herod could hardly have built the fortress and given it the name of his patron's dead enemy. Such an eyesore seems un-Herodian. In short, when Herod cut the block on which he built the Antonia, he did so on a line which, when extended, met the old east wall at a perfect right angle. There were, we see, two conflicting units for determining the lines of Herod's temple platform: (1) the old east wall along the Kidron, and (2) the grid pattern of the city as a whole. Since the ancients did not do flyovers, and because of the enormous size, the irregularity of the temple platform probably went unnoticed, at least by hoi polloi.Given, then, that the outermost east and west walls are not parallel, we cannot construct a north-south line midway between them, as we would like to do in an attempt to find the north-south axis on which the temple was built. On the other hand, following Jacobson, we can take the midpoint between the two Hulda Gates (the Double Gate and the Triple Gate), and then we can construct a line parallel to the west wall. This line crosses through the present-day Dome of the Chain (see No. 12 in the photo above, as well as the enlargeable map above.) Furthermore, if we revise the line of the mount's north wall in accordance with Jacobson, so that it is parallel to the south wall, we can then construct an east-west line midway between them. It too cuts through the Dome of the Chain! On this basis, Jacobson suggests that something important from the time of the temple must have stood at this point. It could not have been the Holy of Holies, because that would have left insufficient space on the east for the Court of Women (where both men and women were permitted, in contrast with the Court of Israel on a higher level to the west, where only men were permitted). But the main sacrificial altar would have fit well here. This would imply, however, that the memory of the altar's position was somehow preserved from the destruction of the temple (70 AD) until the Muslims built the Dome of the Chain about 600 years later. It seems unlikely that this memory would have survived the Roman and Christian centuries when Jews were not allowed into the city (except, for a part of that time, for one day each year) and when the former temple mount served as farmland and as a source of stones. The following seems a likelier tale. We have evidenceMax Kuechler, Jerusalem: Ein Handbuch und Studienreisefuehrer zur Heiligen Stadt, 2., vollständig überarbeitete Auflage, Goettingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2014), pp. 179-184.that the Muslims built a mosque on the south end of the platform, the end closest to Mecca, around 640 AD, soon after conquering the city. The midpoint in the south wall was lined up exactly between the Hulda Gates, which were then open and active (as we infer from the early Muslim lintel over the Double Gate). At this midpoint was a mihrab,A niche, in a wall or freestanding, indicating the direction of Muslim prayer, namely, toward Mecca called Omar's mihrab (still visible, and see the map at the bottom of this page). It was probably the line from this mihrab, parallel to the western wall, that formed one of the two axes determining the site of the Dome of the Chain. Slightly west of the latter, in 688 - 691 AD, the Dome of the Rock was built; it determined a new north-south axis, on which the Al Aqsa Mosque was centered in 711. So what do we know about the location of Herod's temple? It was within the four great walls, and we can be confident that it was on the upper platform, where the underlying bedrock is level for a goodly stretch. If a Jewish pilgrim entered through the Double Gate, she had a chance to immerse herself in a mikveh shown on the map below. (There were two mikvehs on either side, no doubt to separate the sexes.) She then ascended a staircase of normal steps, which was surrounded on both sides by higher, monumental steps like those in the old photo. (Perhaps there was such an arrangement of steps on all four sides of the upper platform.) She now found herself either in the high, broad, level area or in a slightly lower one, built over the gentle slope to the east. We cannot pinpoint Herod's temple more closely. If it was built directly over the series of cisterns that appear on an east-west axis in the map below, then it was north of today's two Domes. Note too that these cisterns were dug into the broadest east-west stretch of level bedrock on the uppermost part of the hill.

{mospagebreak title=Red Heifer}The Red HeiferThis term designates a cow with a reddish coat. As ordained in Numbers 19, its ashes (mixed with spring water, cedar wood, crimson stuff and hyssop) provided ritual purity to Jews who had entered a cemetery or otherwise made contact with corpses. (It was a religious duty to wash, attend and bury the dead, but the act rendered one impure for visiting the Temple.) Purification took a week. A priest would sprinkle you with the mixture on the third and seventh days. Then you would take a ritual bath and be pure. The red heifer had to be without defect (Numbers 19:2). The Rabbis were quite specific about features that could disqualify it. According to Tractate Parah ("Cow") of the Mishnah, no more than nine were sacrificed from the time of Moses till the Temple's destruction in 70 AD. Today none exists, and attempts to breed it have failed. All Jews who have been in some kind of contact with a cemetery or corpse are ineligible, therefore, to enter the precinct of the Temple. Since the Temple precinct, according to a ruling by Maimonides, retained its holiness after the destruction, the ineligibility applies today. There is another restriction as well. Only the High Priest, if there were one, would be allowed to enter the area of the Holy of Holies. But no one is sure where it was.Thus the non-existence of a perfect red heifer and our archaeological ignorance contribute to the peace of the sacred precinct. That said, as of July 2014 there is a movement among a minority of orthodox Jews to prepare for the day of the temple's rebuilding. They do enter the Haram, but most remain on the lower platform, apparently in the belief that the holy place would have been on the upper. Their entry has become a source of friction with the Muslims, who see it as the harbinger of an Israeli takeover.