Hazor: A brief stop at Canaan's largest city

Thanks to the new excavations at Hazor, this may soon change, especially if archaeologists discover the city archive. There must be an archive! At Mari on the Euphrates, a collection of almost 25,000 clay cuneiform documents turned up, dating to the 18th century BC. Most are commercial in nature. According to the Biblical Archaeology Review (May-June 1999), about twenty of these mention Hazor:

"We read of ambassadors coming and going from Hazor and of caravans, laden with gold, silver, textiles and various other commodities, traveling to and from the city. One tablet informs us that Babylon stationed officials in Hazor: 'Two messengers from Babylon who have long since resided at Hazor, with one man from Hazor as their escort, are crossing to Babylon.' Another tablet records several shipments of tin (used in making bronze) to the king of Hazor."

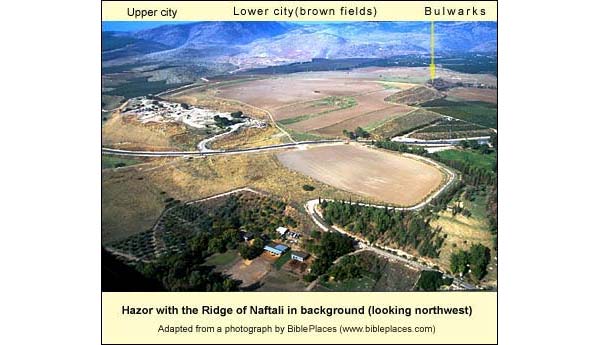

If Mari kept its documents, then surely Hazor kept some too. Excavating the Canaanite royal palace in recent years, archaeologists have found a few, but they still seek the big trove. Hazor was the land's largest Canaanite city. Its upper tellIn general, before the Roman period, a city needed a hill for defense, with a spring nearby. Certain proportions had to be right: the hill had to be small enough so that the population supplied by the spring would suffice to produce enough soldiers to defend a wall surrounding the hill. You needed enough good agricultural land to feed that population. (You also needed peasants in nearby villages to work the land – about ten for every aristocrat in the city.) If you wanted to engage in commerce, you had to be near a decent road. Only certain hills fulfilled these requirements, and therefore people kept building on them. That is why we find layer after layer on some few hills, called tells, while others remained unsettled includes 20 acres, which is not extraordinary. But from the 18th to the 13th centuries BC, Hazor had a lower city of 180 acres! (Compare Megiddo, with 18 acres above and 12 below in this period.) During the Late Bronze Age (1550-1200 BC), it ranked with the great city-states then found in Mycenean Greece, the Hittite Empire and Egypt. These were in frequent contact, sharing in material culture and literature. That is why we find, for example, very specific parallelsFor example, the parallel between the Gilgamesh-Enkidu story and the Achilles-Patroklos story, including the metaphor of the lion's cubs between the Gilgamesh epic of Mesopotamia and Homer's Iliad. The size and might of Hazor are reflected in the Book of Joshua (11:10), which says it "formerly was the head of all those kingdoms." But why did Hazor achieve such eminence?

If we stand on the upper tell, looking north and east, we can see part of the answer.

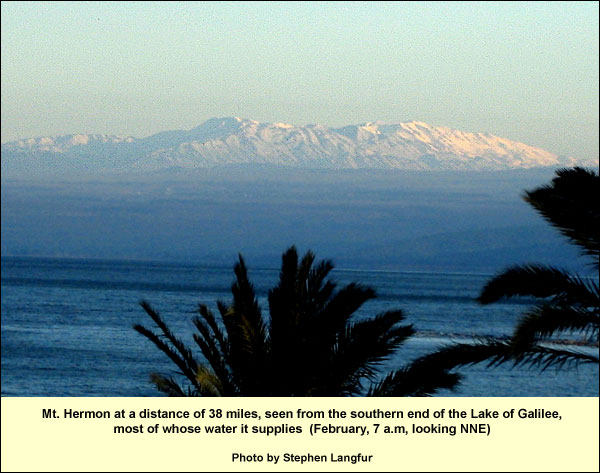

Stretching away from us to the north is the Naphtali ridge. To the northeast we see Mt. Hermon, rising 9146 feet above sea level. On the dimmer horizon to the east, beyond the canyon of the Upper Jordan, are the volcanic cones of the Golan Heights. Finally (and this is the last element we need) on a line between us and Mt. Hermon we see a large stretch of low-slung country; this was the Hula swamp, drained by Israel in the 1950s.

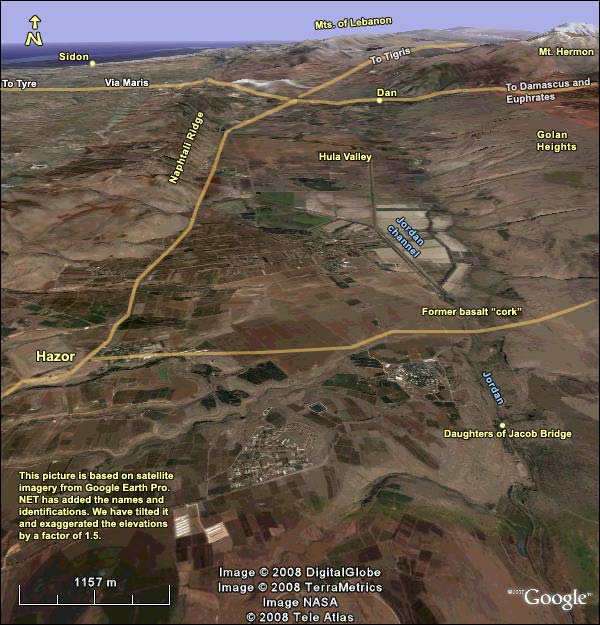

Suppose we are alive in the time of the First Testament (i.e. before the Romans built bridges in the land) and we want to reach Damascus or the cities of the Euphrates. Encountering a river like the Upper Jordan, we have only two options: to ford it or skirt its headwaters. The river lay in a deep canyon, difficult to cross. Ages ago, however, the volcanoes on the Golan Heights spewed out lava. This flowed into the riverbed, and at a certain point due east of us it cooled and formed a basalt barrier. The river water flowing south encountered this barrier, backed up and formed the swamp.

North of the basalt barrier, then, was swamp. South of it was a deep canyon. But the barrier itself served as a ford, over which one could go, continuing unhindered to Damascus. (The "Daughters of Jacob" bridge, named after the nuns of Jacobus (St. James) who used to collect the toll here for their convent in nearby Safed, lies just south of the old ford.)

The other option was to keep close to the Naftali ridge, skirting the swamp, then head east around the major springs of the Upper Jordan at Dan, continuing around the southern edge of Mt. Hermon and up to Damascus.

If the destination was a city near the Tigris, of course, the traveller would not turn east to Dan. Rather, he or she would continue north from Hazor toward Aleppo, Carchemish, Haran and Nineveh.

Both options met at Hazor. It was therefore an essential station on the Great Trunk Road.

As we noted above in connection with Mari, commerce from the Euphrates reached this far south in the 18th century BC. There was also contact from the Nile. Hazor was important enough to Egypt to come in for a curse in the Execration TextsExecration texts: The Egyptians wrote the names of their enemies on clay figures, which they then smashed or maltreated, hoping that a similar fate would befall those designated of the 19th century BC. At that time, then, Hazor alone, among all Canaanite cities, was of interest both to Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Recently the palace - or better, palace/temple - has been unearthed. It is an exciting reconstruction for anyone interested in the ancient world before the great upheaval that preceded Biblical Israel. This is the only instance we have in the land of a large Late Bronze palace that is partly restored and accessible, despite the archaeologist's necessarily destructive hand. Indeed, to excavate it the diggers had first to move a well-preserved Israelite building that stood above. (This four-space Israelite house is now visible north of us on the edge of the tell.)

The palace/temple was built in the 15th century BC and destroyed, along with the rest of the city (and most of civilization) in the 13th. Out front, to the east, are the remains of an open-air platform, probably the base of an altar. It was surrounded by dirt and animal bones. Looking west beyond the altar, we see the line of basalt slabs (orthostats) that surrounded the palace, and, just beyond them, two round basalt bases that supported pillars. The orientation toward the west, the placement of the altar, and the two pillars in front of the building all bring to mind the description of Solomon's Temple (1 Kings 7:15-22).

Yet it was a palace - or also a palace - with a big central hall (the throne room, probably) and rooms around it. On the floor the diggers found a thick layer of ash, thought to be of cedar. The basalt slabs above the foundation, inside and out, were cracked from fire that destroyed the entire city. The heat must have reached 1300 degrees. Above the slabs on the inside ran a line of cedar beams, and above this line, in turn, were mud bricks (no doubt plastered and painted). Those we see have been restored by mixing straw with the original mud. Four cuneiform documents have been found in the structure, two of which mention Mari. This is nowhere near the quantity we would expect, for LB palace officials elsewhere are known to have kept punctilious records. On the other hand, in the rooms on the right were found treasures of ivory (a box and plaques), small bronze statues and cylinder seals. These resemble items found in LB cities at Delos, Mycenae, Athens and Megiddo. The art, in other words, was international. Curiously, however, very little pottery from Mycenae or Cyprus has turned up so far at Hazor.

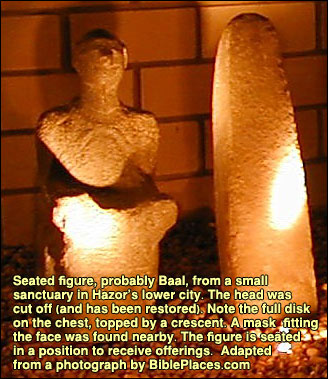

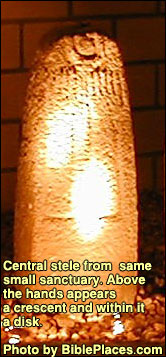

Just inside the palace door, the excavators discovered, in pieces, a basalt statue of Baal (head missing) that is more than three feet tall. It is the largest Bronze Age statue of a god yet found in the land. He is seated, and before him is a huge bowl or vat for libations. We can identify the image as Baal because of the insignia on his chest: a full disc and a crescent, like sun and moon. The same design was found on the chest of a seated deity in a contemporary miniature temple in the lower city (see photo, left), as well as on a stele from an LB temple down there. It recurs in fact throughout the ancient world for at least a millennium.

Why do we start out with something that resembles a temple and then find ourselves in a palace - but with a statue of Baal? Because in the Late Bronze civilizations that we have been talking about (1550-1200 BC) - stretching from Greece to Mesopotamia and Egypt - the king was believed to be divine or semi-divineIn Mycenean Greek, for example, the king was called wanax, a term used later only for gods, and his land was called temenos, a term used later only for land sacred to the gods; basileus was used for a much lower rank. On the ivory panel of a 14th-century couch from Ugarit, the king is shown drinking from the breast of a goddess. The Hittite kings, after 1460 BC, had the title "Hero, beloved of the god (or goddess)." See T.B.L. Webster, From Mycenae to Homer, New York: Norton, 1964, p. 11 and lived with a deity.

In mentioning the might of Hazor, "formerly head of all those kingdoms," the Bible tells us the name of its king: Jabin (Joshua 11:1, Judges 4:2). He would have been the last to sit on the throne of this palace. A palaceThe Late Bronze palace at Pylos in Greece also had a large square throne room surrrounded by smaller rooms and fronted by two narrow forecourts, then a larger court; it also had two pillars before the entrance. that is similar in layout at Pylos in Greece yielded a great many documents, which enabled WebsterT.B.L. Webster, From Mycenae to Homer, New York: Norton, 1964, p. 285 to imagine everyday life there. His description can probably be applied as well to this palace at Hazor:

The palace of Pylos was, therefore, one of a number of Mycenaean palaces which communicated not only with each other but also with Egypt, Syria, and Asia Minor, including Troy (until Troy was sacked). In spite of the difference of scale, landscape, types of manufacture, religion, and language, many elements of life at Pylos would not strike a visitor from Asia Minor as strange: the palace itself with its costly furniture and precious objects of ivory, gold, silver, and lapis lazuli, gifts received and gifts to be dispensed, the archive room with its minute records of every department of life in war and peace, the divine King with his special estates and his Companions, partly military leaders and partly administrative officials, the wider circle of nobility who formed the chariotry and provided the mayors responsible to the palace for the surrounding towns and villages, which were centres for the craftsmen and land workers of the different districts. The King of Pylos sat on his throne 'tippling like an immortal'. The brightly colored frescoes of his palace had as their subjects the griffins and lions, which gave him divine protection and symbolized his power, the seated goddess, who lived in his house and gave him instructions, the legend of the Siege [basis for the Iliad - SL] which his poets sang... At the appointed times he caused offerings to be made to the gods...

Near the palace the expedition found a huge lion carved in relief in basalt. Its mate had earlier been discovered deliberately buried in a pit near a temple a kilometer away in the lower city. The two originally formed the jambs of a gate, perhaps of that lower-city temple. On the other hand, a monumental staircase has been discovered connecting the mounds, and the two Hazor lions may well have formed part of a gate there.

All this came to an end with the great upheaval that overthrew the civilizations of Mycenae, Asia Minor and the Levant, down to the borders of Egypt - from Pylos to Ugarit, from Hattusas to Hazor. The tell of Hazor remained empty for more than a century, until the first modest Israelite settlement appeared. Even Solomon, whose construction at Hazor wins Biblical mention,"This is the reason of the levy which king Solomon raised, to build the house of Yahweh, and his own house, and Millo, and the wall of Jerusalem, and Hazor, and Megiddo, and Gezer." (I Kings 9:15) did not develop the entire upper mound, and the enormous lower city was never inhabited again.

Logistics:

Telephone (04) 693 7290 Nature Reserves and National Parks (Main office: 02/500-5444) Opening hours: April 1 through September 30, from 8.00 - 17.00. (Entrance until 16.00)*

October 1 through March 31, from 8.00 - 16.00. (Entrance until 15.00)* *On Fridays and the eves of Jewish holidays, the sites close one hour earlier. For example, on a Friday in March one must enter by 14.00 and leave by 15.00.