Gamla

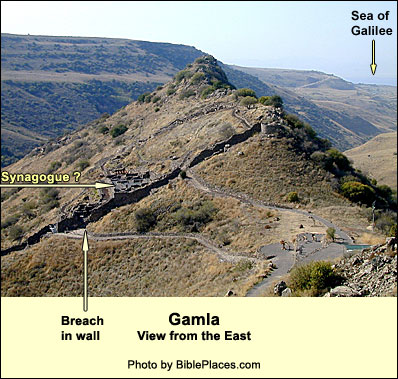

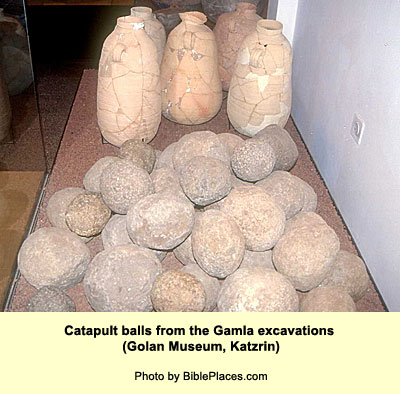

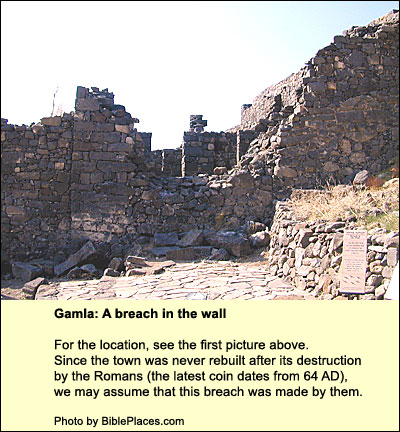

Gamla is on the Golan Heights, east of the Sea of Galilee. Josephus locates it "opposite Tarichea on the far side of the lake." Tarichea is often identified with Magdala , on the lake's western shore, but this identification cannot be maintained. The town was built on the southern slope, which included a large public building, probably a synagogue. The houses must indeed have seemed to hang in mid-air, and one wonders what might have led people to live at such a place. The strong defensive position must have been a major factor. In peacetime there was plenty of water: rivers flowed all year round on either side of the hill. In war the inhabitants relied on cisterns. We do not yet know what they did for a living. The hill was first settled, apparently, by Jews returning from the Babylonian exile. Then there is a gap in our knowledge, but Gamla probably fell to the forces of Alexander the Great around 332 BC. The HasmoneanThe Hasmoneans: family of Judah Maccabee ("the hammer") and his brothers, who revolted successfully against the Greek Empire in 167 BC. They purified and re-dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem, establishing the festival of Hanukah ("dedication"). They ruled till 63 BC, and their domain extended almost as far as King David's king, Alexander Yannai (aka Jannaeus), who ruled from 103 until 76 BC, included it among his conquests. Thousands of his coins have turned up in the excavations. Like the other Jewish cities east of the Jordan, it fell under Roman control after Pompey's conquest (63 BC), but four decades later AugustusOriginally Octavian, the adopted son of Julius Caesar. He became one of the triumvirate, along with Marc Antony and Lepidus, that ruled Rome after Caesar's assassination in 44 BC. At the Battle of Actium in 31, he defeated Antony and became the sole ruler of the Roman Empire, remaining in power until his death in 14 AD. The Senate awarded him the name Augustus ("revered"), Sebastos in Greek. The stability during his reign introduced a Roman peace (pax romana) upon the Mediterranean world (a factor that later helped make possible the rapid spread of Christian faith) gave it and the surrounding region to HerodHerod ruled the land under Roman auspices from 37 - 4 BC. After his death, the Romans called him "the Great" because of his building activities. Christians chiefly remember him, however, as the killer of the innocent children (Mt. 2: 16). From Gamla came a rebel leader named Hezekiah, whom Herod executed. This Hezekiah was the father of another proud Gamlan, Judah, founder of the Sicarii ("dagger men"), whose descendant was Eleazar Ben Yair, the Jewish leader at Masada. When the first great Jewish revolt broke out in 66 AD, Gamla belonged to the realm of Herod's great grandson, Agrippa II, a client king for the Romans whose capital was at Caesarea Philippi. (This is the Agrippa who heard Paul speak at Caesarea Maritima.) Josephus, the future historian, was one of two generals appointed to lead the revolt in the north. He claims that he built a wall around Gamla. One has been found, in fact, but just on the eastern portion, which was the only side that required artificial defense. (See picture above.) The rebellious cities of Galilee fell one by one to the Roman general Vespasian. Jewish refugees fled toward Gamla, but Agrippa (who had been besieging it for seven months) posted cavalry to block them. In any case the inhabitants could not afford to admit more people, because of the limits on space, food, and water. Vespasian came up with his legions from Hammat near Tiberias. He took a position on the hill overlooking the city, Josephus tells us - and Josephus was probably with him, for he had recently been captured. The best viewing point for telling Gamla's story, on a ledge southeast from the city, is perhaps the place where Vespasian stood. The Romans began building siege ramps on the eastern side, the only place where access was conceivable. Agrippas approached the wall to negotiate a surrender, but a slinger wounded him on the elbow and he withdrew. Then the Romans pressed the siege. Having completed the ramps, they brought up the battering rams. When the Jews tried to ward them off, they were met by volleys of catapult stones. (The excavators found vast quantities of these, as well as Roman arrowheads.)

At last the combination of Roman might was too much. The defenders began to flee to the upper parts of the town, and the Romans, breaking through, surged after them. This proved to be a mistake. The Jews, with nothing but the sky above and the enemy below, had no choice but to turn and fight, and this they did with ferocity. Against their fury, the pursuing Romans found themselves in a trap. For the houses at Gamla were built very close together on the slope, joined by the narrowest possible alleys. (This too the archaeologists could confirm.) Caught between their own forces charging up the hill and the desperate Jews above them, the soldiers found no recourse but to jump onto the roofs of the houses at their feet. These collapsed beneath the armored weight, leaving many Romans caught beneath timber and stones, while others were choked by dust. When one house fell it knocked down those beneath, so that to an observer the effect must have been as if the camel had shuddered, shedding its load. The rebels, for their part, saw in this turnabout the hand of God and redoubled their efforts. "The debris furnished them with any number of great stones, and the bodies of the enemy with cold steel: they wrenched the swords from the fallen and used them to finish off those who were slow to die. Many flung themselves to their death as the houses were actually falling. Not even those who fled found it easy to get away; for unacquainted with the roads and choked with the dust, they could not even recognize their friends, but in utter confusion attacked each other." (WarThe Jewish War. Translated by G.A. Williamson. Penguin, 1981 IV, 27) Among the beleaguered Romans near the top of the hill, Josephus tells us, was none other than Vespasian himself! Moved by the plight of his soldiers, reports the bootlicking historian, the great general had "forgotten his own safety." Now seeing the danger he was in, he remembered his long life of battle and his reputation for courage. Cool-headedly, he bade the soldiers beside him to link their shields with his. Then they held together like a tortoise,The Roman shields were designed in such a way that some soldiers could link their shields around their group while others used theirs to make a roof, so that the whole formation resembled a tortoise; this could be used not only for protection, but also as a bridge withstanding the barrage of spears and stones. When the barrage weakened a little, they carefully stepped backward, picking their way among the debris and the bodies, always keeping formation. Then the barrage came again, and they stopped and waited until it slackened. In this way, foot by foot, barrage by barrage, they made their way backwards down the slope and out through one of the breaches. The Romans had suffered a disastrous defeat. Vespasian assembled the survivors and spoke to them, gently reprimanding them for having charged so recklessly up the hill. (But what was he doing up there?) "Such crazy impetuosity," he said, "is foreign to us Romans, who win all our victories by efficiency and discipline."

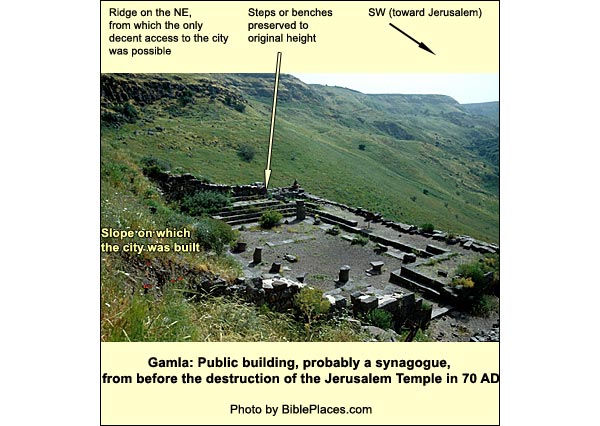

Perhaps the defeat was even graver than Josephus reports, for the Romans delayed attacking again, and they did not (or could not) prevent most of the rebel fighters from escaping out of the hungry, thirsty city. Vespasian waited until his son Titus arrived. After choosing a force of 200 cavalry and some infantry, Titus noiselessly entered Gamla. Those who remained were no match for him. Avenging the deaths of their comrades, the Romans slaughtered young and old. Blood, writes Josephus, flowed down the slopes. Some of the defenders managed to make it to the peak, where, like the first time, it was a choice between one death and another. Vespasian had rejoined the fray, and it was he who led the assault on the camel's neck. Boxed in, the Jews rolled down rocks, causing heavy casualties, "while they themselves on their lofty perch were almost out of reach. But to ensure their destruction they were struck full in the face by a miraculous tempest, which carried the Roman shafts up to them but checked their own and turned them aside." Despairing, the Jews flung their wives and children, and finally themselves, into the immense ravine far below. More leaped than died by the sword. The surrounding landscape is every bit as dramatic as the story. Dramatic too is the hike down to the city for a hands-on visit, and even more dramatic for some of us will be the hike back up (about 700 feet). Recently, however, the Parks Authority has paved a road thereto (not to be used in the rain). But remembering the putative valor of Vespasian, and given time, one can visit the breach in the wall, pictured above, and just beyond it a large public building (20 meters by 16). In order to get enough level space for this edifice, the Gamlans had cut back into the hillside on the west, while building a terrace on the east.

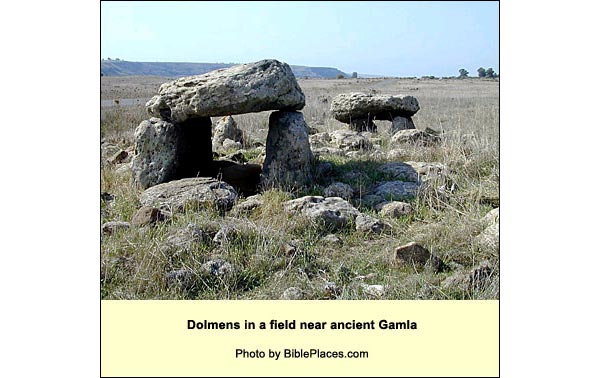

If this building was a synagogue, it is among the earliest yet found. For Gamla never rose again. (The latest coins unearthed at the site date from 64 AD.) A number of features are similar to those of later ancient synagogues: It was the only large public building. The main entrance was in the SW wall, facing Jerusalem, and just beyond it was a ritual bath. There were benches all around. The lintel had an engraving of a rosette pattern flanked by palm branches. There was a niche in the western wall (for scrolls?). All that is missing to nail the matter home is a seven-branched candelabrum or a religious inscription. There are trails leading to the top of the camel's hump; special caution is required as one gets closer to it. The peak is a good place to read Josephus' account concerning the end of the battle. After leaving the city and making the climb back up, we may pause at a special observation point to take in a very different feature of Gamla. The cliffs in its canyons provide nesting places for the land's largest flock of Griffon vultures. (The flock was severely diminished, however, after many died from eating wolves that had been poisoned by farmers.) In the afternoon these stately scavengers cruise back to their nests. The platform brings you as close to vultures as you will ever hope to be. There is much else to visit in the nature reserve. For example, the well-preserved houses of an abandoned village (near the parking lot), which includes one from the ByzantineThe Byzantine period – that is, the period of the Eastern Christian Roman Empire –may be dated from 330 AD, when Constantine re-named the city of Byzantium "Constantinople" and dedicated it to the God of the Christians. Its end, in this land, came in 638, when the Muslims took Jerusalem. Elsewhere it lasted much longer: Constantinople finally fell to the Turks in 1453 period. One can examine the use of long basalt slabs for roofing. There are also the ruins of a monastery, but one is not allowed inside. A short walk takes us into a field of dolmens. A dolmen ("table" in the Breton language of France) is a structure made of two large upright stones and a flat capstone. These probably date from the late third millennium BC, when the megalithic culture was flourishing in the Golan. A hint as to their use comes from the islands of Malekula near New Zealand, where the dolmen functioned (well into the 20th century and perhaps still today) as the gate through which the soul was to go after death. The problem was that the goddess of death would stand in front of the gate like a goalie in soccer to catch the soul. Each family had a dolmen, and periodically it would come to sacrifice a pig on the "table" above. The idea was to spoil the goddess with pork. When a family member died, the others would again sacrifice a pig, and while the goddess was gorging herself on the table above, the soul of the dead would scurry through the gate to eternal life. (For a detailed account, see LayardJohn Layard, The Stone Men of Malekula, London: Chatto and Windus, 1942).

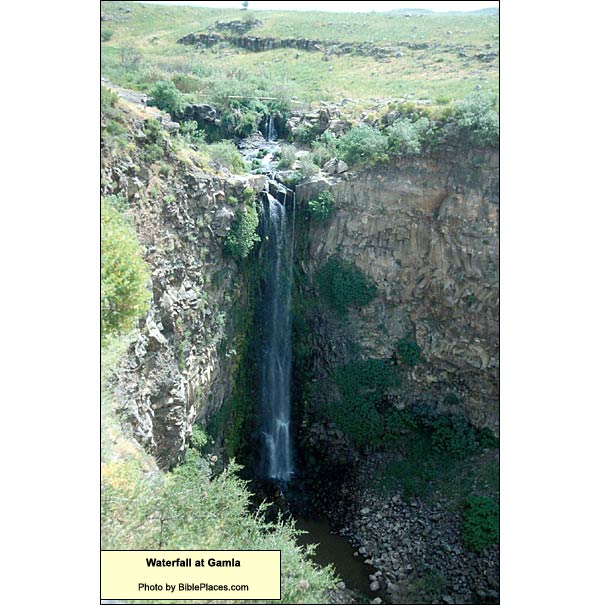

A longer walk (about half an hour) brings us to an overlook, from which we can see a waterfall tumbling 50 meters into the Gamla River.

Logistics: It is important to phone Gamla in advance, because there are days when the army trains here and the site is closed. Gamla's phone: 04-682-2282. Gamla is a national park and nature reserve. If you want to do the overview plus a visit to the fabled Jewish city and back, reckon on about 4 hours at the site. There is now a paved road to the city. The entrance has a gate that can be opened by the Parks Authority. This road is not to be used in the rain. Nature Reserves and National Parks (Main office: 02/500-5444) Opening hours: April 1 through September 30, from 8.00 - 17.00. (Entrance until 16.00)* October 1 through March 31, from 8.00 - 16.00. (Entrance until 15.00)* *On Fridays and the eves of Jewish holidays, the sites close one hour earlier. For example, on a Friday in March one must enter by 14.00 and leave by 15.00.