Beth Shean

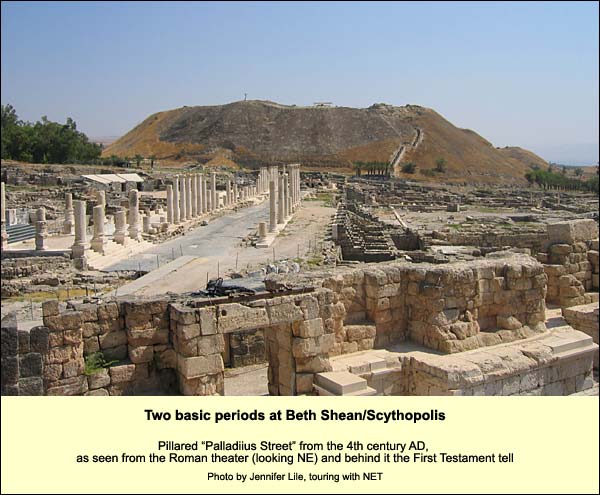

Several indicators show that the ancients appreciated Beth Shean's strategic importance: 1. In the mid-second millennium BC, it became the chief Egyptian military base in the area, as indicated by numerous Egyptian finds on the tell, more than anywhere outside Egypt. 2. Under its Greek name, Scythopolis, it was - according to Josephus (War: 3, 446) - the biggest city in the Decapolis. It was the only Decapolis city west of the Jordan, providing a key link between Caesarea Maritima and the rest of the league. 3. On again organizing the land in 400 AD, the Byzantines made Scythopolis the capital of Palaestina Secunda. Caesarea Maritima became the capital of Palaestina Prima, Petra (though some say Bostra or Elusa) of Palaestina Tertia. Very roughly speaking, two times are represented here: that of the First Testament and that of the Roman-Byzantine period. The usual way of visiting the site brings us first to the Roman-Byzantine city, and we shall follow that order here, moviing back in time to the First Testament and the story of Saul.

If you want to view this material on a live tour guided by Dr. Steve Langfur, please start here .

{mospagebreak title=Scythopolis} Scythopolis: the Roman-Byzantine City

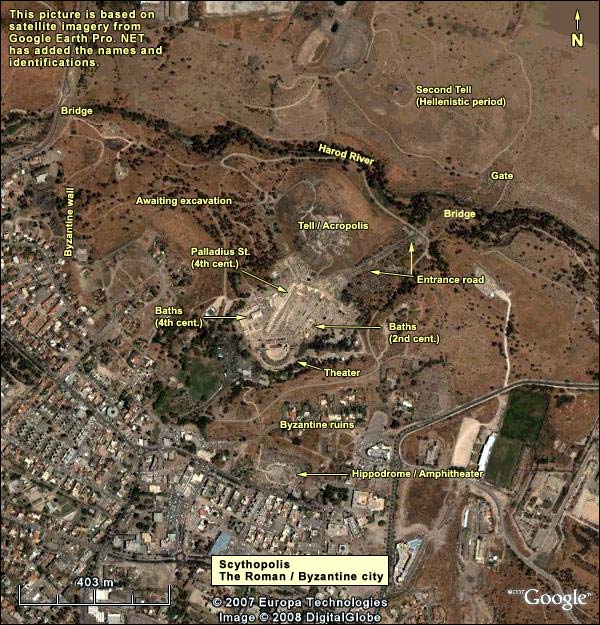

In the time of the First Testament, the city was confined to the tell. By the Hellenistic period (332 BC), however, the population was too large for this mound alone, so some people moved to the hill across the river. Eventually, under the pax romana, the sense of security increased, and most activities shifted to the valley below. The tell became the acropolis ("top of the city") with a temple to Zeus.

Before 1985 the entire area, except the theatre, was covered with eucalyptus trees. In that year the modern Beth Shean had a serious problem of unemployment. Archaeologists knew there was plenty waiting to be dug. Here was a major city of the Decapolis, but only the tell and the theatre had been excavated. Since Decapolis cities such as Jerash (Gerasa) in Jordan are splendid, this must be splendid too! And so they were able to put 200 breadwinners from Beth Shean to work.

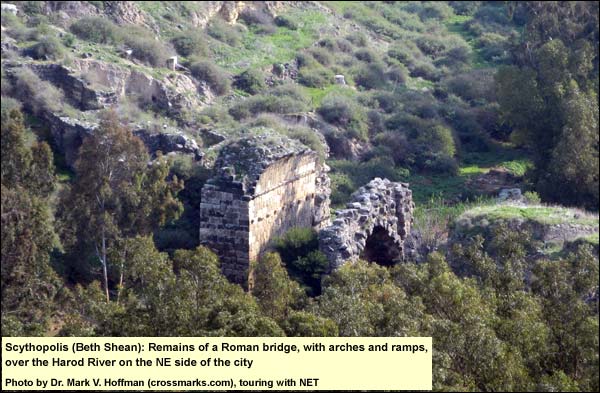

Over the Harod River, northeast of the tell/acropolis, are the remains of a triple-arched Roman bridge. (The Romans were the first to introduce bridges to the land.) Beyond it was the main entrance to the town.

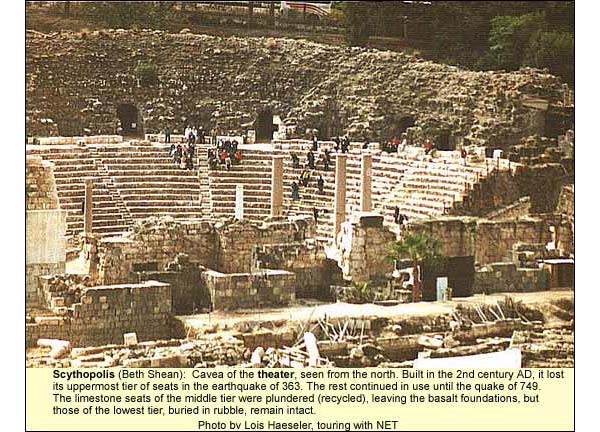

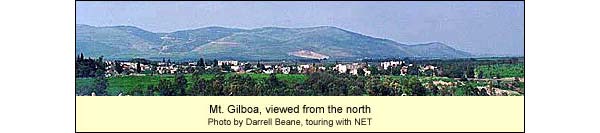

The tell's southern edge affords a grand view of the Roman/Byzantine ruins. The downtown area extended beyond the theatre to an amphitheater. (See the satellite photo above.) Indeed, the area of the Byzantine city was a square mile (Jerusalem's Old City is less, a square kilometer). The population, in the Roman period, may have been 20,000, in the Byzantine, 50,000. The theatre dates from the 2nd century AD. Today it has two tiers of seats, but then it had three. (The earthquake of 363 brought it down, and it was never repaired to its original height.) The seats were all of white limestone imported from Mt. Gilboa, and they were set at an angle to catch the natural rise of the sound waves from the stage. About 7000 people could fit inside. On hot or rainy days, the whole top would be covered with a canopy, made perhaps from the town's famous linen. The niches for the supporting posts are visible in the seats. This raised a problem of stuffiness, which the Romans solved (Oscar {jtips} Seyffert, Oskar. Dictionary of Classical Antiquities. Meridian|SeyffertA league of cities under Roman auspices. Sometimes ten are mentioned, sometimes more. They included Damascus (an honorary member), Hippos, Gadera, Gerasa (Jerash), Pella, Scythopolis and Philadelphia (Amman) . Other cities were later added to the original ten. In the first century AD, however, no coins minted in these cities mention a Decapolis. Matthew (4:25) and Mark (5:20, 7:31) write of Jesus' passing through it. All other historical references to the league date from after the outbreak of the Jewish revolt in 66 AD. (See Rainey and Notley, The Sacred Bridge, Jerusalem: Carta, 2006, pp. 361-362) informs us) by squirting a mixture of saffron and water into the air between acts. The alcoves beside the exits, unique to this theatre, may have held the spraying machines, especially needed in so hot a valley.

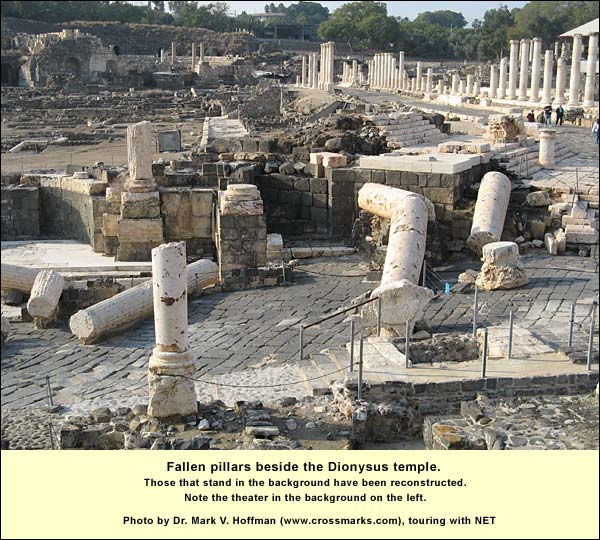

East of the theatre, a 2nd-century Roman bathhouseBefore the Empire, Roman baths were for bathing. After undressing, the bather would carry his towel, oil and scraper (strigil) into the warm room (tepidarium), to adjust for the torments ahead. Then he would enter the hot room (caldarium), heated by a hypocaust: oven-heated air flowed between two floors, one half a meter or so above the other. Here he would rub himself with oil, wait a while, and scrape it off. Then he would cross to the frigidarium, plunging into cold water stretched all the way to a porch or stoa, now indicated only by its line of impressive pillars. We may visit the public restroom. On a close-up view, we note beneath the rows of seats a ditch, through which was channeled the southern river of Scythopolis, taking the waste to the Jordan. Men and women used the restroom at different times. There were no dividers between the seats. It was a favorite place for conversation. Returning to the line of impressive pillars at the eastern end of this bathhouse: originally, between them and the street, there was a shallow reflecting pool, so that one saw them twice. The Byzantines filled the pool and built shops, calling the street "Sylvanus Street" after the Samaritan lawyer who financed its reconstruction in 515. On January 18, 749 an earthquake brought the city down, including these pillars. One covered the skeleton of a man reaching for a bag of coins. This quake devastated much of the country, especially cities in the Syro-African rift valley. We have literary records of many Jewish casualties in Tiberias. Scythopolis never recovered, although a small town was built over part of the ruins, incorporating pillars in the foundations. We follow Sylvanus Street toward the tell, encountering next on our left a square platform. This supported a monument that greeted those coming from the main gate. It included statues made of green Athenian marble. Next we find a nymphaeum (a public fountain with statues of nymphs), and next, at the corner, a temple to Dionysus, patron god of the city. Today we see the steps of this temple, along with the huge pillars of its facade that fell in the earthquake (above). The Byzantine Christians got rid of its inner chamber (cella), but left the facade. Here then we encounter, as at Sepphoris, the cult of Dionysus.

A ceremonial staircase connected the Dionysus temple with a Zeus temple on the acropolis. For Zeus was the father of Dionysus. The mother, however, was not Hera, his wife, but Semele, a mortal. Disguised as an old woman, Hera wheedled the pregnant Semele into wheedling Zeus to show himself in his true form. This was the lightning stroke, which turned Semele to a crisp. Zeus saved the embryo and sewed it into his thigh, out of which, at term, burst the god of flowing wine. The columned street coming down toward the tell, intersecting Silvanus at the temple, is called Palladius, after its 4th-century funder. (See photo above.) In a mosaic inscription, Palladius assures us that he donated the money for the street from his own pocket. (He does not say how the money got into his pocket, but that would take too long for a mosaic inscription.) To the south of this street was the agora or marketplace, including some striking animal mosaics. To its north is an open semicircle with small rooms radiating off it. In one of them we find a 6th-century mosaic showing a rather unhappy looking Tyche (the luck of the city), with the urban wall on her head for a crown. She holds a cornucopia. We may wonder what a goddess like this is doing in a Christian city, but then we see that the date palm growing out of the horn is a cross.

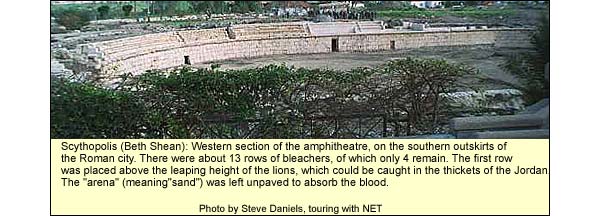

Several of the floors in the rooms of this semicircle have mosaics containing erotic poems in Greek. Continuing westward on Palladius street, we find a 4th-century bathhouse on the north side. Since the reconstructers did not know what the roofs looked like, they made roofs they were sure would not resemble the originals. Inside, however, we find the country's best-preserved saunas (calidaria). We have seen two bathhouses. Five have been found, including one for lepers. We have not, however, seen the remains of churches. There was one on the acropolis. But the Byzantines wanted the downtown area for bathing and commerce, shunting religion to the margins. On the hills north of the Harod River are the remains of a 6th century monastery, as well as Jewish and Samaritan synagogues. The monastery, built by "the lady Mary" (perhaps the wife of a Byzantine official) includes a large mosaic. The months are depicted, each "represented by a man equipped for an occupation typical of the season." (Murphy-O'ConnorMurphy-O'Connor, Jerome. The Holy Land: An Archaeological Guide, 4th edition. London: Oxford, 1998 , p. 195). Palladius street leads us up to the modern entrance. We can then walk or drive around to the amphitheatre ("double theatre"). Such structures, among them the Coliseum in Rome, were used for the bloodiest spectacles of Roman public life: gladiator and animal fights, as well as execution by animals. Only the arena (from Latin harena, meaning sand, which was used to soak up the blood) and the first few tiers of benches remain, but in the 2nd century AD it had between eleven and thirteen rows, accommodating about 6000 people, including soldiers from the Roman Sixth Legion. In all of Asia Minor no amphitheatres have been found, but in this small land we know of five so far: here, in Beit Guvrin (the best-preserved), in Shechem, and two (from different periods) in Caesarea Maritima. The reason: after the first Jewish revolt, Roman legions were stationed here, and the armies loved spectacles of blood. Yet not only the armies. From the time of Julius Caesar, no Roman politician could gain favor with the people if he did not stage extravagant spectacles ending in death. The effect was aphrodisiac. After the killings inside, prostitutes made a killing at the gates.

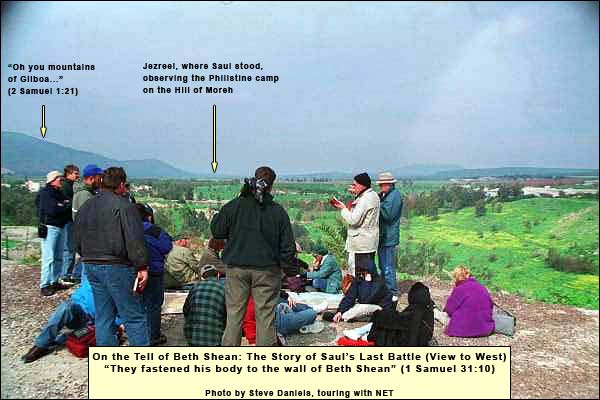

In this example at Scythopolis, the first row is more than ten feet above the arena, and of course there would have been a fence as well, protecting the drooling spectators from the beasts and gladiators. These beasts would have included lions, caught in what was still then the "thickets of the Jordan" (Jeremiah 49:19Jeremiah 49:19 “Behold, one will come up like a lion from the thickets of the Jordan against a perennially watered pasture; for in an instant I will make him run away from it, and whoever is chosen I shall appoint over it. For who is like Me, and who will summon Me into court? And who then is the shepherd who can stand against Me?” ). (The last lion was sighted in the 13th century.) During the persecutions by Decius (250 AD), Valerian (258) and Diocletian (304), Christians would have undergone martyrdom here. Given such memories, the Byzantines had no interest in amphitheatres. They buried this one with a neighborhood, whose basalt-cobbled streets we may walk. {mospagebreak title=Saul} View from the Tell of Beth Shean: The death of Saul in context We climb the tell to a point on its north side, near a partial reconstruction of the Egyptian governor's mansion. From here we have a complete view around. To the southwest are the mountains of Gilboa, stepping down into the Jezreel Valley. The very lowest step is Tel Jezreel, where Ahab and Jezebel had their winter capital, near Naboth's kerem (vineyard or olive grove). The Harod River, flowing below us, has its origin in a spring at the foot of Gilboa, where Gideon chose his 300 (Judges 7). Sighting up the Jezreel Valley, we are looking toward the pass at Megiddo, with Mt. Carmel to its right. North of Tel Jezreel, just across the valley, is the Hill of Moreh, where the Midianites were camping when Gideon's band sneaked up, and where later the Philistines camped when Saul stood at Jezreel in fear for his life. To the right of Moreh, closer in, is a rise of land that prevents us from seeing Mt. Tabor; just on the other side of it lies Ein Dor, where Saul consulted with a witch.

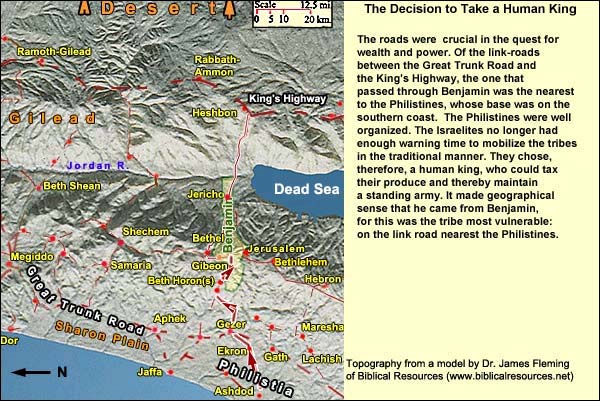

If we complete our turn, facing east, we see the Jordan, toward which the Midianites raced in panic on their camels, and Gideon called out the tribes of Israel to cut them down at the fords. Above are the heights of biblical Gilead, atop which, about twenty-five miles to the east, ran the King's HighwayThe "King's Highway" (Numbers 21:22) was the second major trunk road. It stretched from Arabia Felix (Yemen today, then rich in perfumes and spices) through Transjordan to the great oasis at Damascus. Upon this stretch fell the last rains from the Mediterranean. East of the highway lay 400 miles of desert from Damascus to Arabia. On it, almost due east of us, was Ramot Gilead, where Omri and his descendants often fought the Arameans, trying to complete their grasp on the key to wealth and power. Turning ESE (or enlarging the photo above right), we see a village on the place of ancient Pella, a Decapolis city where the Christians of Jerusalem took refuge during the First Revolt against Rome. If we now ascend to the first layer of hills (not the horizon), we are in the area of Jabesh Gilead, which figures in the story of Saul. The choice of Saul as king Archaeological surveys indicate a marked decline in settlement through most of the land in the second half of the second millennium BC, followed by a sudden upsurge in the 12th century. Most of the new settlers had been semi-nomads, herders of small livestock, who now took up agriculture. Some of their communities developed into towns we associate with biblical Israel. The "Israel" of these semi-nomadic settlers was at first a not-so-reliable confederacy of clans and tribes, each intent on keeping its independence. When a crisis arose, they depended upon the charisma of a leader to unite them, and the process took time. As long as their enemy was equally slow to mobilize, they could get by without a standing army, that is, without a human king. The shift to human kingship was spurred by pressure from the Philistines (ca. 1050 BC). By then the Israelite settlers had put roots in the soil: they had something permanent they did not want to lose. What is more, unlike their earlier enemies, the Philistines did not need much time to mobilize. Based on the southern coast, they could strike quickly up through the territory of Benjamin on the Beth Horon ridge, which was part of the southernmost good link road between the western Trunk Road and the King's Highway.

The Israelites no longer had enough warning time to mobilize the tribes in the old manner. They chose, therefore, a human king who could tax their produce and maintain a standing army. It made geographical sense that he came from Benjamin, for this was the tribe on the link road where the Philistines first put the pressure. (See map above.) Saul of Benjamin was a transitional figure. He started like the charismatic leaders before him: by rescuing people. When the Ammonites besieged the Israelites of Jabesh Gilead, they demanded that each man surrender his right eye. The men of Jabesh appealed to Saul, who made a raid across the Jordan and rescued them (1 Samuel 11). After Saul's coronation, however, something goes wrong with him. Perhaps charisma and permanent kingship do not go easily together. The God who gives charisma can also take it away. In Saul's case, it was replaced by spells of madness. As the Bible puts it, he lost his earlier contact with God. The loss is explained in two ways: he did not wait for Samuel before performing a sacrifice, and he did not execute the Amalekite king as God had commanded (1 Samuel 13: 7-14 and 1 Samuel 15). Standing on Tell Jezreel, looking at the Philistines camped on the Hill of Moreh, the king knew he no longer had that contact. The death of Saul Having lost his contact with God, Saul sought to take counsel with the human source of his authority, Samuel. Here there was a catch, however: Samuel was dead. Undeterred, Saul and some of his officers disguised themselves and sneaked around the eastern side of Mt. Moreh to Ein Dor, to a witch. Here too was a catch, for Saul had banned witchcraft. Nevertheless, he persuaded the woman to "bring up" Samuel. And then we have 1 Samuel 28:9-25. David, having fled from the jealous Saul and gathered a band around him, was by this time a Philistine vassal with his own city, Ziklag. He was therefore duty bound to join the Philistines in battle -- a sticky wicket, if he ever wanted to rejoin his people. Fortunately for him, however, the Philistines remembered where he came from and decided not to trust him. They sent him back to his town. We take up the story again at 1 Samuel 31:1-13. The word is brought to David in Ziklag. He sings this lament (2 Samuel 1:19-27):

19“Your glory, Israel, is slain on your high places!

How the mighty have fallen!

20Don’t tell it in Gath.

Don’t publish it in the streets of Ashkelon,

lest the daughters of the Philistines rejoice,

lest the daughters of the uncircumcised triumph.

21You mountains of Gilboa,

let there be no dew nor rain on you, neither fields of offerings;

For there the shield of the mighty was vilely cast away,

The shield of Saul was not anointed with oil.

22From the blood of the slain,

from the fat of the mighty,

Jonathan’s bow didn’t turn back.

Saul’s sword didn’t return empty.

23Saul and Jonathan were lovely and pleasant in their lives.

In their death, they were not divided.

They were swifter than eagles.

They were stronger than lions.

24You daughters of Israel, weep over Saul,

who clothed you in scarlet delicately,

who put ornaments of gold on your clothing.

25How are the mighty fallen in the midst of the battle!

Jonathan is slain on your high places.

26I am distressed for you, my brother Jonathan.

You have been very pleasant to me.

Your love to me was wonderful,

passing the love of women.

27How are the mighty fallen,

and the weapons of war perished!”

2 Samuel 2:1 - It happened after this, that David inquired of Yahweh, saying, “Shall I go up into any of the cities of Judah?” Yahweh said to him, “Go up.” David said, “Where shall I go up?” “To Hebron, he said."

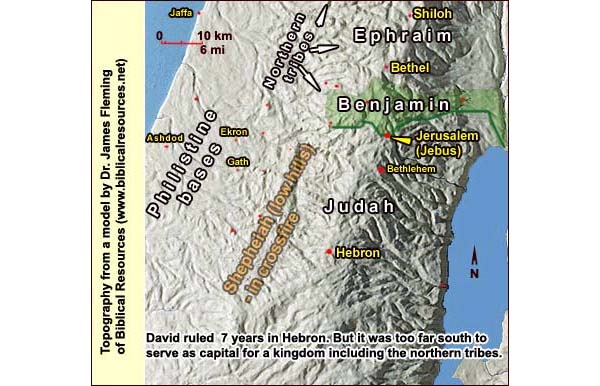

The death of Saul left the tribes extremely vulnerable to the Philistines. David went to Hebron in his home tribe of Judah, whose people submitted to his kingship.

After seven years the other tribes approached him and asked that he protect them as well. Hebron was too far south, though, and too Judah-bound, to serve as a satisfactory capital for a kingdom including the northern tribes. Then David's eyes lit upon a city that straddled the border between Judah and the north, belonging to no tribe: Jerusalem.

{mospagebreak title=Logistics}

Logistics

Phone: (04) 658 7189 Nature Reserves and National Parks (Main office: 02/500-5444) Opening hours: April 1 through September 30, from 8.00 - 17.00. (Entrance until 16.00)*

October 1 through March 31, from 8.00 - 16.00. (Entrance until 15.00)* *On Fridays and the eves of Jewish holidays, the sites close one hour earlier. For example, on a Friday in March one must enter by 14.00 and leave by 15.00.